1088

HUNTING THE WOLF

By David Hancock

Wolves have long been regarded as a threat to man, to sheep farmers especially. Saxons called January the Wulf-monath, or Wolf-month, because wolves became more troublesome then through the great scarcity of food in that month. In his Chronicles of the Kings of England, William of Malmesbury states that the tribute of 300 wolves' heads payable yearly by the King of Wales to Edgar (959-75) ceased after the third year because 'he could find no more'. In his book The Last Wolf, published by Little, Brown in 2017, Robert Winder describes how in 1290, a Shropshire knight, Peter Corbet, cleared his county, and the adjoining ones, of wolves, with his pack of hounds, earning the name of 'Mighty Hunter'. His campaign, matched by others, paved the way for extensive sheep-farming, for England to become wool-rich and change the economic future of large parts of the country. Easier to get rid of wolves on an island, yes, but the wool trade transformed the country - only made possible by hunters and, before the invention of firearms, their hounds. The wolf, the main threat to sheep in so many countries, is a powerful potentially savage predator, well able to defend itself and capable of weighing a hundredweight. In his Wolves and the Wilderness in the Middle Ages (The Boydell Press, 2006) Aleksander Pluskowski writes: "In medieval northern Europe wolves were the top land predators...Packs of two to forty-two animals form the basic units of a wolf population...There is a close relationship between wolf density and prey abundance, with higher numbers of wolves occupying smaller territories in areas with higher densities of ungulates".

Pluskowski went on to explain that wolves are flexible and very opportunistic predators, able to hunt prey weighing as much as 100 kilogrammes or as little as one kilogramme. Wherever wolves were found and livestock had to be protected, the big shepherd dogs like the shepherd's mastiff here and the German, Dutch and Belgian varieties or the even bigger flock guardians, such as the Pyrenean, the Tatra and Estrela Mountain Dogs and the Maremma in Italy, were utilised. Whenever an offensive had to be mounted however, faster but similar-sized hounds were used, with the Russian wolfhounds inspiring Turgenev and Tolstoi by their heroic endeavours. The Russian wolves were often hunted in winter because their pelts were thicker and therefore had more commercial value. But it was their threat to livestock which stimulated their being hunted. Whole packs of wolves can move to new hunting grounds if the prey density attracts them; in 1944 a new wolf pack settled near a Saami community at Vaesterbotten, killing fifty reindeer. The development of protective or hunting/tracking dogs to combat them is a natural reaction.

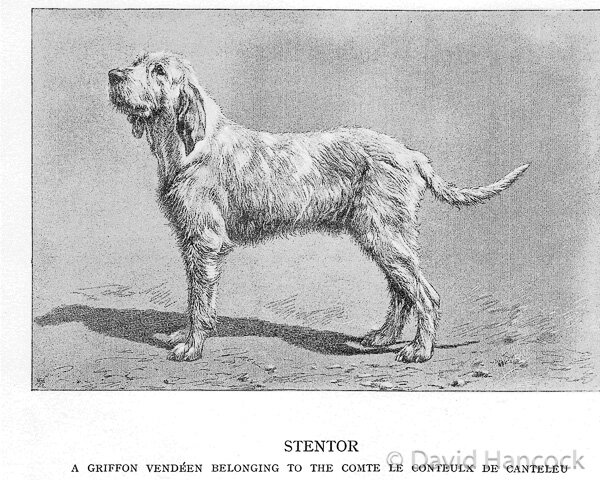

France was one country particularly populated by wolves; as early as 1467, Louis XI created a special wolf-hunting office, whose top member was appointed from the highest families in the land. In the French province of Gevaudan in the 1760s one wolf is alleged to have killed more than fifty people, the majority women and children. At the end of the French revolution in 1797, 40 people were killed by wolves, tens of thousands of sheep, goats and horses slaughtered by them, and, in some remote districts not a single watchdog left alive. A total of 1,386 wolves were killed in France in 1883. The dense forests led to the French mainly hunting them with packs of scenthounds rather than coursing them with faster hounds. The griffon type of rough-coated large hound was used to run down wolves in wooded country, some used on boar as well. The boar lance or two pronged fork was sometimes used to hold down the outrun or captured wolf. A wolf lance, held in the right hand, and a protective gauntlet worn on the left hand and forearm, was routinely used in close combat with the wolf.

Huge shaggy-coated hunting dogs were used by the Celts in their central European homeland in the eight century BC and these accompanied them on their migrations to Britain, Ireland and Northern Spain from the fifth to the first century BC. In his Gentleman's Recreation of 1675, Nicholas Cox wrote: "Although we have no wolves in England at the present, yet it is certain that heretofore we had routs of them, as they have to this very day in Ireland; and in that country are bred a race of greyhounds which are commonly called wolfdogs, which are strong, fleet and bear a natural enmity to the wolf. Now in these greyhounds of that nation there is an incredible force and boldness..." Behind the Irish Wolfhound there are at least three distinct types: Just over one hundred years ago, Fitzinger identified "...The Irish Greyhound, next to the Indian and Russian Greyhound, is the largest specimen of the greyhound type, combining the speed of the Greyhound with the size of the Mastiff. The second type is the Irish coursing dog, a cross between the Irish Greyhound and the Mastiff or bandogge. He is shorter in the neck, with a coarser skull, broader chest and heavily flewed lips. " The third variety he described as a cross between the Irish Greyhound and the shepherd dog, being low on the leg and having a shaggy coat. The latter sounds like a shepherd's mastiff or native flock guardian, a bigger version of the Irish Beardie or hirsel. Holinshed, in his Chronicles of Scotland of 1577, made a point several times of describing the wolf-hunting dogs, not as one type, but two - one of greyhound type, the other a 'hound', a heavy hound such as a hunting mastiff of old.

In his British Animals Extinct Within Historic Times of 1880, James Harting sets out some valuable points about wolves in Britain and the hunting of them. He states that hunting the wolf, wild boar, fox and deer were the favourite pastimes of the nobility in the Anglo-Saxon period and 'the Dogs which they employed for these various branches of the sport, were held by them by them in the highest estimation.' Referring to the legend of Gelert in Wales, who killed his dog thinking it had harmed his son, whereas it had slain the wolf trying to do so, Harting wrote that 'The dog referred to belonged probably to the race called by Pennant "the Highland Gre-hound", of great size and strength, deep-chested, and covered with long rough hair. This kind was much esteemed in former days, and was used for hunting by all the great chieftains in preference to any other.' Harting records that in Edward III's time, Conan, Duke of Brittany, in 1342, 'gave pasture for cattle through all his new forest at Richmond in Yorkshire to the inmates of the Abbey of Fors in Wensleydale, forbidding them to use any mastiffs to drive the Wolves from their pastures.' The use of a 'mastiff' as a hunting dog or heavy hound has long been forgotten by today's show breeders. Many of the mountain dogs and flock-protecting breeds of today started out as 'shepherds' mastiffs', able to do battle with wolves.

"In Anglo-Saxon times every two villeins were required to maintain one of these dogs for the purpose of reducing the number of wolves and other wild animals. This would indicate that the Mastiff was recognised as a capable hunting dog..."

'The Complete Book of the Dog' by Robert Leighton (Cassell) 1922.

Hunting the wolf went on in Ireland long after it had ceased in England, Campion, in his History of Ireland of 1570 mentions the pursuit of the wolf there with 'Wolfhounds'. He wrote that 'The Irish are not without Wolves, or greyhounds to hunt them; bigger of bone and limme than a colt.' In past times the word greyhound was used to refer to coursing hounds not a distinct breed. Sir James Ware wrote, in his Antiquities of Ireland of 1658: '...those hounds which, from their hunting of Wolves, are commonly called 'Wolf-dogs', being creatures of great strength and size, and of a fine shape.' Wolfhounds or wolfdogs were so valued in Ireland that in Kilkenny in 1652 there was a "DECLARATION AGAINST TRANSPORTING WOLF DOGS: For as much as we are credibly informed that wolves do much increase, and that some of the enemy’s party, who have laid down arms and have liberty to go beyond sea, and others, do attempt to carry away several such great dogs as are commonly called wolf-dogs, whereby the breed of them, which is useful for the destroying of wolves, would if not prevented speedily decay. These are, therefore, to prohibit all persons from exporting any of the said dogs out of this kingdom, and searchers and other officers of the Customs in the several ports and creeks of this dominion are strictly required to seize and make stop of all such dogs, and deliver them either to the common huntsman appointed for the precinct where they are seized upon, or to the governor of the said precinct.” In the Travels of the Grand Duke Cosmo III of 1669 the author states that wolves were common in Ireland 'for the hunting of which the dogs called 'mastiffs' are in great request'. As Lord Altamont showed much later, there were two kinds of wolf-hunting dogs in Ireland, the rough-coated hound and the smooth-coated mastiff-like hound.

The Irish Wolfhound was re-created in the latter half of the 19th century, when, in 1863, an Englishman, Captain George Augustus Graham, a Deerhound breeder, noted that some of his stock threw back to the larger type of Irish Wolfhound. He obtained dogs of the Kilfane and Ballytobin strains, the only suitable blood available in Ireland at that time. He then interbred these with Glengarry Deerhounds, which had Irish Wolfhound blood in their own ancestry. In due course he produced and then stabilised the type of Irish Wolfhound which he believed to be historically correct. Out-crossing continued, with Capt Graham using the blood of a 'great dog of Tibet', then, between 1885 and 1900, seven Great Dane crosses were conducted, and Borzoi blood used several times in the 1890s. This is of course how all hunting dogs were once bred, good dog to good dog, irrespective of breed titles. Closed gene pools are a modern phenomenon.

In his book Dogs since 1900, published by Dakers in 1950, Croxton Smith wrote: “…at the beginning of this century Mr IW Everett, whose Felixstowe Irish Wolfhounds obtained a dominant influence for many years, resorted to a cross with a brindle Great Dane. This alien blood was apparent for some time in the flatter skulls of the Felixstowe Wolfhounds, but it disappeared, and for a long time now the breed has been kept in its purity.” I have talked to Irish Wolfhound breeders of the present time who are still very anxious to avoid shaggier coats and the flatter skull because of this background to the breed. Those words of Croxton Smith about purity very much typify twentieth century thinking about recognized breeds of dog, often placing purity ahead of soundness and health. In the 21st century slowly but surely attitudes are changing, so that coefficients of inbreeding and genetic health are to the fore. Fitness for function is becoming fashionable once more!

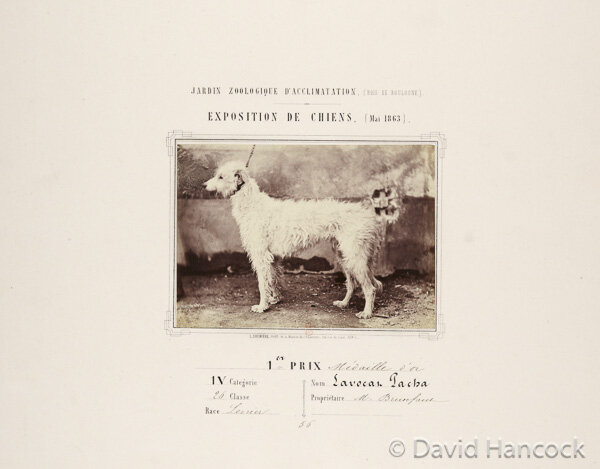

European man has long utilized huge white rough-haired dogs in their age-old campaign to protect their livestock from wolf attacks, as the Pyrenean flock guarding breeds illustrate. There are a number of depictions of such big white wolfhounds in antique art, in the work of Oudry, Desportes and Snyders, for example. It is rare nowadays to see a pure white Irish Wolfhound however, despite this coat colour being permitted in the breed standard. In 1585, the Lord Deputy Perrott sent to Lord Walsingham ‘a brace of good wolfdogs, one black and one white’. In 1623, the Duke of Buckingham asked the Earl of Cork for some white ones, claiming that this colour was the most in favour when given as presents to monarchs. Wholly white dogs can feature accompanying problems, such as albinism, deafness and sometimes eye complaints too. The pied colouration was shown in Lord Altamont’s Irish ‘wolfdogs’ of the late 18th century but, like pure black, has perhaps been overwhelmed by the main coat colours: grey brindle, red, fawn, wheaten and steel grey. Perhaps the Deerhound, Great Dane and Tibetan Mastiff infusions have dwarfed those from the Greyhound and the Borzoi. ‘Irish spotting’ or white feet and throat on a solid colour is frowned on in this breed, whatever the merits of the carrier. A wide-ranging coat colour presentation in a breed must always be healthier than a restrictive one. Pure white Deerhounds are no longer wanted despite their featuring in Victorian paintings. The Kurdish hound was favoured in a white coat. But, whatever its coat colour, does the re-created Irish Wolfhound have the right breed title? It has never hunted wolves; perhaps The Great Irish Dog would be a more fitting name, rather like the Greater Swiss Mountain Dog in Switzerland.

In India, the wolf has been hunted using similarly shaggy-coated hounds, like the Banjara or Vanjari, 28 inches high and grey mottled, and the 30 inch Rampur Hound, the smoother-coated Shikari dog of Kumaon, the Great Dane-like Sindh Hound, the beautiful ivory-coated Rajapalayam and the graceful Mahratta Hound. Such types disappear when the threat from wolves recedes but their value to man was considerable. Our contemporary affection for the wolf would not have been shared by those living in remote villages in India or a number of European countries in the middle ages. Wolves, operating in packs, threatened livestock and sought human prey when desperate for food. Powerful dogs of the flock guarding type were needed to protect livestock and strong-headed very fast hounds were needed to course them. Hunting wolves for sport may not appeal to 21st century sympathies, but that should not lessen our admiration for wolfhounds, their bravery and athleticism in the hunt, when wolf numbers required checking. But it's the Russian wolfhound which has gained the greatest following across the globe. But as with the Irish dog, is this the best title or sub-title for the Borzoi? Russian Fox-catcher would be more accurate, for the breed has caught far more foxes than wolves in the last century.

Although the Russian wolfhound is known to kennel clubs around the world as the Borzoi, the word itself means light, swift and agile, being used rather loosely just as greyhound was in Britain, levrier in France and windhund in Germany. The Borzoi was more commonly used for fox and hare coursing and the Russians once referred to Asiatic, Polish (Chart or Chort), Crimean or Tartar Borzoi (these more like Salukis) and the Circassian variety too. The Scottish Greyhound (Deerhound) was used on wolves and other quarry, coursing hounds having long been used in a wide variety of pursuits. It is easy to forget when looking at contemporary breeds that their ancestors did not breed true to type, being judged solely on performance, not on conformation to a set standard. Behind the modern single breed of Russian Borzoi, there are barrel-chested Caucasian Borzoi, huge curly-haired Courland (the Baltic province) Borzoi and bigger-boned Crimean dogs. This type was found as far west as Albania and Serbia too.

The graceful athletic build of the Russian wolfhound has long drawn widespread admiration. Undoubtedly the attractive silky coat of the modern pedigree Borzoi enhances its physical appearance. But as with the Saluki and the Ibizan Hound, of this type of swift hound, there were varieties of coat in the Borzoi too. The Hunter's Calendar and Reference Book, published in Moscow in 1892, divided the Borzoi into four groups. First, Russian or Psovoy Borzoi, more or less long-coated; second, Asiatic, with pendant ears; third, Hortoy, smooth-coated and fourth, the Brudastoy, stiff-coated or wire-haired. But whether the hounds were sleek or bristle-haired, wolf coursing in Russia before the Revolution was what fox-hunting was to Britain and par force hunting was to France. Tsar Peter II kept a pack consisting of 200 coursing hounds and over 420 Greyhounds. Prince Somzonov of Smolensk had 1,000 hounds at his hunting box, calling himself Russia's Prime Huntsman. Better known was the hunt with the Perchino hounds near Tula on the river Upa, where Archduke Nicolai Nikolsevich established a hunting box in 1887 and hunted two packs of 120 par force hounds, 120 to 150 Borzoi and 15 English Greyhounds. To ensure sufficient hardiness for winter wolf hunts, both horses and hounds were kept in unheated stables or kennels.

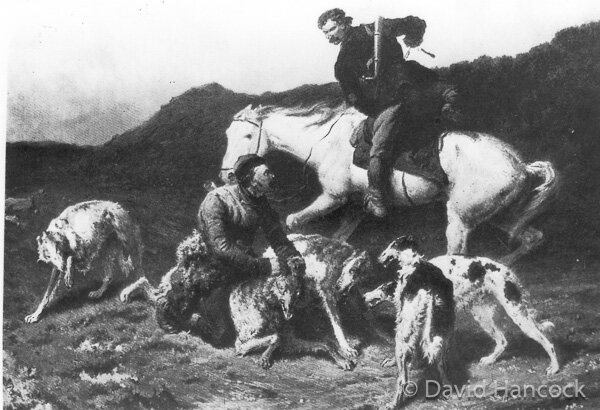

Usually 20 leashes of Borzois were taken to a hunt, each consisting of two males and a bitch. The hunting season was summer coursing (June to early August) on hare or fox, then summer training for Borzois in August. This consisted of 20 kilometres walking or trotting with the hunt horses, followed by advanced training on captive wolves in early September, then the wolf-coursing season from mid-September to the end of October. Hunting from sledges sometimes took place from October, with mounted beaters putting up the wolves, which were often fed to keep them in the hunting grounds. In the Perchino game reserve, between 1887 and 1913, 681 wolves were killed, as well as 743 foxes, 4,630 brown hares and 4,026 white hares; Borzois, often working with scent hounds, obtaining the bulk of this bag, some specialising in seizing the wolf by the ear to avoid damage to the pelt, reducing its market value.

The robustness, fitness and stamina of the hounds must have been remarkable. Coursing with Borzois in Tsarist Russia called for a high standard of horsemanship and superbly-trained hounds. Each mounted handler rode with his three hounds on long leashes, slipping the hounds whenever a wolf was either put up by the extended line of mounted beaters or flushed out of the woods by scent hounds of the Gontchaja type. Many of us would find it difficult enough to control three Borzois on short leashes whilst dismounted! The Borzoi is still important for the Russian fur trade, for they catch foxes without mauling them and ruining their pelts. This also avoids the crueller use of iron spring traps.

The wolf-dog function in the United States was first carried out there by what they call staghounds, big rough-haired hunting dogs, crossbred in pursuit of function not whim, although hunters’ preferences do manifest themselves in their anatomies. In his Hunting Dogs of 1909, Oliver Hartley refers to a Minnesota 'wolfer' who averaged 35 wolves a year and who pinned his faith in the long-eared variety of hounds, with features of strength, endurance, good tonguers and stayers. He had been advised that the best dogs for coyotes, were part English blue (i.e. Greyhounds,) and Russian stag (i.e. Borzois,). He wrote that the English blue are very fast and the stag are long-winded, with the grit to make a good fight. He also wrote that another admired and capable dog is the one-half Scotch stag hound (i.e. Scottish Deerhound,) and one-half Greyhound. He recorded that a Wisconsin hunter believed that the best breed for catching and killing coyotes is made by one-half shepherd (our working collie) and one-half hound, being quicker than a hound and trailing just as well on a hot trail. He wrote too that another fast breed for coyotes is a quarter English bull, a quarter Bloodhound and one half Foxhound. Here is a classic example of blending blood in pursuit of performance, the hunter's endless challenge.

The wolf menace has not gone away from central Europe. They are now active again in the Hautes-Alpes; in 2014 over 9,000 sheep were killed there by them, 23 in a single raid. It does not take giant hounds, 32 inches at the shoulder, to hunt them. But hunting them does demand substantial and determined hounds to do so successfully. The bigger the dog the bigger is the need for soundness of physique; their ability to lead a fulfilling life is prejudiced when their anatomy itself is a handicap. Breeders and owners who rate the coat and the size ahead of structural soundness reveal at once their disrespect for their own breed. Wolfhounds are extraordinary hounds; their past courage and athleticism deserves our respect. They were never intended to be ornaments or fashion accessories; they evolved and then survived because they were superlative hunting dogs, and could still be.