1094

SAVED BY OUR DOGS - GLOBAL EMERGENCY FOR MANKIND

By David Hancock

Perhaps arrogantly, we thought that the days when primitive man relied on dogs to fill his pot could never return. Then, without warning, came Apocalypse Now, Armageddon Mother Earth! The post-mortems on the global disaster of 2050 found it difficult to separate the immense impact of the substantial asteroid that hit Iran that year and whether the shock to the earth's crust caused the succession of serious earthquakes right across the Far and Middle East, some accompanied or followed by disastrous tsunamis. The loss of satellite-routed communications was catastrophic, the destruction of modern life, as we knew it, just wholescale and world-wide. Man was sent back, in so many places, to primal living. Those that best survived the breakdown of cities, the loss of communications, the serious lack of food and water, were the primitive tribes and simple rural communities that had needed so little before this international disaster, but knew how to survive such a life-changing event - supported by their dogs! Rather like primitive man across the globe before the invention of firearms, electricity and then electronics, the simple societies coped, the sophisticated societies could not. Life without mobile phones and the internet had arrived!

We have long forgotten the value to primitive man of dogs that could hunt animals for food and fur, lure wildfowl within arrow range, drive off dangerous wild beasts, wolves especially, and thereby provide sustenance, give protection and support, like killing vermin, just about every basic activity that man conducted. Before this calamity we could afford to keep hounds as pets or in support of our leisure interests; we had long lost the use of water-dogs and decoy-dogs but retained them as companions without a function. We still utilised dog's herding instinct, one rooted in hunting methods before their pastoral role. We still used sled-dogs but mainly for leisure not essential transport. We still used transhumance dogs to protect sheep from predators but the latter are much reduced. The invention of firearms gave man great power and minimised the value of huge protective dogs, some preserved merely as pets, but bred away from functional capability. How we failed them!

I believe the hounds came first, not of course looking like contemporary breeds of hound in conformation, but first in functional use for man. Buffon, I know, for one, argued that the sheepdogs came before them but I can find no logic in that. For to use sheepdogs primitive man had first to become a farmer of sorts yet man was a hunter-gatherer long long before he became a farmer. Although I acknowledge that in some places sheep were domesticated before dog. The sheepdog's instinct for rounding up numbers of sheep or singling one out for attention almost certainly developed from the hunting style of primitive wild dog and is still practised in the wild today. But before man kept animals of his own, he needed to fill his pot with the meat of wild animals and what better ally than a tamed wild dog acting as a hound. Such a canine ally could assist man to locate game in the first place, be used to drive the game towards precipices, pits or human hunters with their primitive weapons such as spears. Subsequently these domesticated dogs were to be trained to drive selected game into specially-constructed enclosures or into cleverly-positioned nets. In due course very fast game was hunted using very fast dogs, big game was hunted with huge 'seizers' or hunting mastiffs and feathered game hunted using dogs which could either silently (like a setter) or noisily (like a bark-pointer) indicate the location of the quarry. In time the tracking dogs became specialist hounds, able to hunt boar or hare, wild asses or deer, bison or elk. In Europe, the names of the early breeds in the hunting field indicate their function: bufalbeisser (buffalo-biter), barenbeisser (bear-biter) and bullenbeisser (wild bull-biter). The bull-lurcher is their nearest contemporary equivalent; if you live near a deer park or large moor, the red deer would be their quarry. If you live near a French forest (or, here, in the Forest of Dean!) wild boar would be.

This group of dogs originated as heavy hounds used to assist man in the hunt for the bigger quarry: horned and hoofed beasts of great size, immensely difficult to seize and 'hold' but a supreme provider of meat. Primitive hunters would have found great benefit in having sizeable dogs to pull down such substantial quarry. This group of dogs were the canine big game hunters, of infinite value to human hunters and, unlike hounds pursuing smaller quarry, all too often sacrificed their own lives in providing a source of food to humans. Their desire to persist in the hunt has led to their being misused by man in combat with other animals and even each other. Their matchless power in the hunt has led to their being prized for their sheer size and impressive appearance. They should be prized for what they are: superb canine athletes, valuable protectors and steadfast companions, never misused to bolster shaky egos or become associated with the misguided public parading of outward belligerence.

Our increasingly town-dwelling world limits their activity: for employment, exercise and therefore spiritual release. Their past service to man however should ensure that we breed them wisely, respect their basic needs and honour their heritage. They represent a quite remarkable feature of man's past needs and activities in a primitive world. They bring qualities of tolerance, restraint, controlled power and innate gentleness that we should admire. In an asteroid-devastated world they can fill the pot and sustain mankind in their hour of immense need. Seizers that could tackle an auroch deserve respect. They triumphed on land against four-footed quarry, but there were once of course dogs that triumphed on birds too.

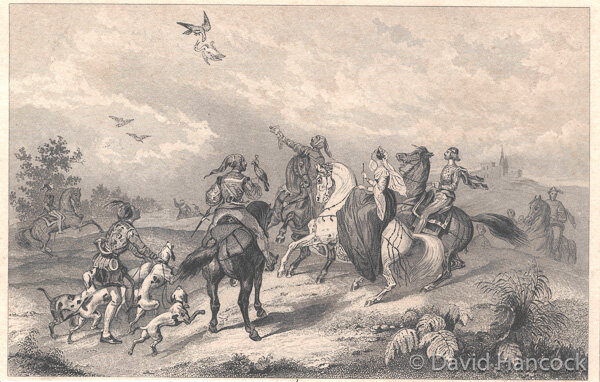

Hunters were ‘armed’ long before the introduction of firearms, with the spear, the bow and arrow, the boar-lance and the bolt-firing weapons to the fore. The net could also be described as a weapon, being used to capture rabbits or envelop game birds indicated by setting dogs. Before the invention of firearms, hunters were reliant on dogs which could indicate unseen game and not run-in, as well as those which could retrieve valuable bolts, especially from water, when used on wild fowl. In the late middle ages, the netting of birds was not a simple matter; dogs had to be trained to find the quarry and ‘hold’ them whilst crouching expectantly but with immense patience. To further deter the birds from taking off, a kite-hawk, a device resembling a bird of prey, would be flown over them. Alternatively, a falcon could be positioned above them, either flown free or at the top of a long pole, within sight of the birds. Each stratagem ensured the birds clung to the ground, so enabling the hunter to proceed. Once the targeted, transfixed birds were grounded by this system, the netsmen could advance with their net and trail it over the prone dog and cast it over the almost hypnotised birds. Gamekeepers would often spread obstacles in open fields to prevent game being poached in this manner.

Finding and then catching flying prey meant locating them with ‘setting dogs’ which then lay low to allow the hunters’ net to be drawn both over them and the crouching dogs, or chiens couchant. There are many setters to this day that instinctively crouch low rather than stand and point in the classic pose. In continental Europe a draw-net or tirasse was employed; this involved the dogs crawling slowly towards the stationary birds, gradually driving the alarmed but not flight-prone birds towards the approaching nets-men. In such a way, the dogs ‘worked’ the birds into the net, rather as a well-trained collie urges sheep to move but not run. The value to the hunter, both here and on the continent, of a dog which instinctively found game on the ground, indicated its find, then almost hypnotised it into staying on the ground until a net descended on it, must have been priceless. But hunting in and over water brought different challenges.

It is therefore worth setting out the references we do have of water-dogs in medieval times. In the ancient world anyone found guilty of killing a water-dog was subject to a most severe penalty. The first written account of a Portuguese Water Dog is a monk's description in 1297 of a dying sailor being brought out of the sea by a dog with a black coat of rough long hair, cut to the first rib and with a tuft on the tip of the tail, the classic water-dog clip. Water-dogs came in two types of coat: long and harsh-haired or short and curly-haired. The French Barbet displays the former, the Wetterhoun of Holland and our Curly-coated Retriever the latter; the Portuguese Cao d'Agua or water-dog features both. In The Sketch Book of Jean de Tournes, published in France in 1556, the great rough water-dog is depicted, a big shaggy-headed dog swimming out to retrieve a duck from a lake.

In Dr Caius's Of English Dogs of 1576, he described the Aquaticus, a dog for the duck, but blurs the water-dog with the spaniel. He does however in 1569 provide his naturalist friend Gesner with an illustration of a Scottish Water Dog, retriever-like but with pendant ears. Writing in 1621, Gervase Markham recorded: "First, for the colour of the Water Dogge, all be it some which are curious in all things will ascribe more excellency to one colour than to another as the blacks to be the best and the hardier; the lyver hues swiftest in swimming...and his hairs in generall would be long and curled..." In 1591, Erasmus of Valvasone wrote a poem on hunting, which will appeal to Lagotto (the Italian waterdog) fanciers, referring to "...a rough and curly-haired breed that does not fear sun, ice, water...its head and hair resemble that of the ram, and it brings the bird back to the hunter merrily."

The invention of firearms and the subsequent improvements in the range and accuracy of guns in the shooting field brought about a large measure of redundancy in the ancient art of decoying, now rarely known about by sportsmen let alone practised. We still of course put out bird-dummies to entice feathered game like woodpigeon and duck, but it is extremely rare to come across decoy-dogs at work, despite their time-honoured employment in this field in many different countries. In Canada (with the Toller), in Holland (with the Kooikerhondje) and certainly in one place in England however, this ancient canine skill is being perpetuated. The skill of the decoy dog lies in giving the inquisitive ducks only fleeting and seemingly alluring glimpses of its progress through the reeds and undergrowth, taking great care never to frighten them or even give them cause for suspicion.

Before the use of firearms and indeed in the days when their range was very limited, these dogs must have been enormously valuable to duck-hunters. The distinctive feature of dogs used in this way was the well-flagged tail. Their colour was usually fox-red, leading to some being referred to as fox-dogs, partly also because foxes will entice game by playful antics in a very similar vein. Clever little fox-like dogs have been used in many different countries in any number of ways in the pursuit of game: in Finland, their red-coated bark-pointer Spitz breed transfixes feathered game, and ties down hoofer quarry, by its mesmeric barking whilst awaiting the arrival of the hunters; in Japan, the russet-coated Shiba Inu was once used to flush birds for the falcon and the Tahl-tan Indians in British Columbia hunted bear, lynx and porcupine with their little black bear-dogs, which were often mistaken for foxes.

In Canada, probably taken there by European colonists, there is the Toller or Nova Scotia Duck-Tolling Retriever, a golden-red medium-sized dog with the distinct look of our Golden Retriever about it. This Canadian dog is about 20" at the shoulder with a compact muscular build, alert, agile and determined, a strong swimmer, easy to train and a natural retriever. To be a successful duck-toller, such a dog needs a playful nature, a strong desire to retrieve and a heavily-feathered tail that is in constant motion. The skill of the hunter lies in throwing the stick for the dog the right distance at the right moment so that the ducks are not frightened away by the menace of an advancing dog, but made curious by the enticing waving of its bushy tail. The dog makes a normal retrieve of the stick but does so in a playful manner with plenty of tail-wagging. This decoy dog does not entice the birds by deliberately frolicking about, as foxes have been seen to, but is used essentially as a retriever of sticks. This playful retrieve however does lure the duck within range of the arrow, net or similar simple weapon.

If sporting breeds are to be there ready for unidentified future calamities, there has to be a planned renaissance, not an abrogation of responsibility for breeds we specifically bred and developed over several centuries to assist us in the sporting field. It would be a major step forward if breed clubs took up this challenge, although I suspect that challenge certificates have more appeal for them. Just as the UKC in the United States fathers a wide range of field activity for dogs, so too could our own KC, extending their field trial and agility interest. Sporting organisations too could cut their losses and diversify their sporting agenda, in the interests of the hounds alone, if only to have the canine ingredients of a rebirth one day, should field sports regain favour. To neglect the best interests of the dogs would be shameful. Positive thinking is called for, not intellectual collapse. The so-called 'civilised world' is just not made to cope with global catastrophes and all that embraces, but dogs can!

Throughout our social history as a nation, changing social attitudes have influenced our use of dogs in the name of sport, rather than survival. Few social attitudes have been shaped by global disaster! Barbaric activities like badger, bear and bull-baiting, rat-killing competitions and dog fighting contests have rightly been outlawed. Nevertheless, we still prize and perpetuate that canine gladiator, the Bull Terrier, even if some legislators retain the view that once a fighter always a fighter. This irrational approach doesn't extend however to Zulus, once a superlative martial race or the Vikings, as my peace-loving Danish friends point out to me, with some amusement. The spirit behind the trail-hound and Whippet racing, the Bloodhound packs which hunt a human trail, lure-chasing with Irish Wolfhounds and even nocturnal rat-catching in a maggot-factory, as the late Brian Plummer recommended, provides such encouragement for the future of sporting dogs. Perhaps, sadly, the single-issue lobbyists have them too in their sights, as they now have trail-hounds. Zealots defending their version of the 'natural world' forget that dog is part of that world.

For a nation that has given the world a score of distinguished sporting breeds, many of them preferred to the local breeds on sheer merit, we must now work to ensure that all the dedicated work of our forefathers is not thrown away - especially if the stars predict an asteroid hitting Mother Earth 'sometime in the future'. In many emergencies we can be saved by our dogs; there never will be contingency plans to offset or survive a global catastrophe but by ensuring that our age-old sporting dogs can still function, whether as crouching game-finders, hunting mastiffs, water-dogs, decoy-dogs, 'dogs for the net' in hawking, bark-pointers, haulage dogs, scenthounds, sighthounds or just smaller dogs to kill vermin, we would have many quite simple ways of ensuring that some of us survive!