1099

WORDS TO FASHION A BREED - ON THE SCOTTISH DEERHOUND

By David Hancock

Books on breeds of dog have disappointed in the last half century or so; so many have been written to a canine-book specialist formula and lack both authority and style. Even sadder and just as tiresome to the reader is the lack of writing ability in their authors, so often chosen because of rosettes won not literary skill. But a well-written book on a breed, penned by a genuine expert and edited by a scrutinising publishing house, such as Crowood or Quiller, can truly influence a breed, becoming almost the 'bible of the breed'. I recently re-read Kenneth Cassels' privately-published soft-back on the Scottish Deerhound, regrettably entitled A Most Perfect Creature of Heaven (after Sir Walter Scott's phrase on this breed in his The Talisman) produced in 1997. Firstly, it would have helped every librarian and bookseller if the book's title had been The Scottish Deerhound - 'A Most Perfect Creature of Heaven'; secondly a competent, experienced editor would have improved this book appreciably; thirdly this book merited top-class illustrations - it is a really good book on this breed and clearly written by a great expert on this breed. For me it had value way beyond its purely physical content. I truly learned from it!

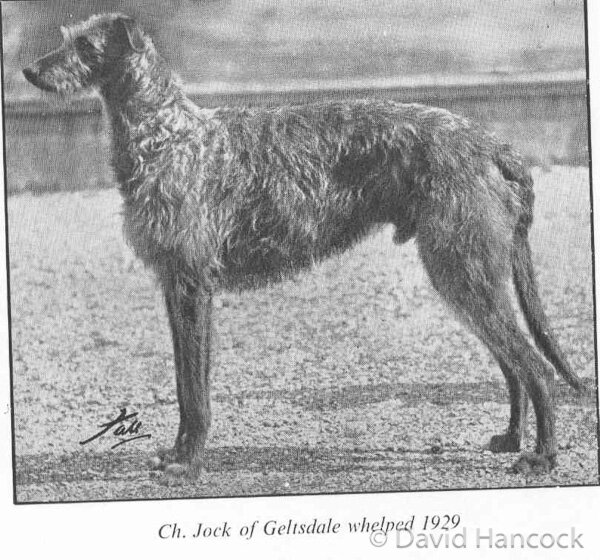

The Scottish Deerhound has never lacked good breeders, with Sir John McNeill, Lord Edward Bentinck, Cameron of Lochiel, GW Hickman and Harry Rawson leading. It is likely that the Deerhound has retained its essential type because it seems to attract distinguished owners and breeders. It has also attracted a remarkable number of lady-breeders: Miss Branfoot, Mrs Armstrong, Miss Richmond, Miss Reoch (Bridge Sollers), Miss Doxford of the Ruritania kennel, the Misses Loughrey of the Ross kennel, Miss Bell of the Enterkine kennels, Miss Linton (Geltsdale), Miss Hartley (Rotherwood) and Miss Noble (Ardkinglas) would grace any breed club register. Some of these have written ably on the breed, but this book of Kenneth Cassels, who did so much to promote the sporting use of this breed from the 1950s onwards, is rather special and his words must be used to continue to 'fashion the breed' especially as its numbers slump - only 209 being registered in 2016.

Early on in his book, Cassels quotes from a talk he once gave to a Deerhound Club Seminar where he had stated that 'for a working Deerhound there are three essentials: 1. Courage and keenness. 2. Speed and agility. 3. Size and strength.' But he stressed that 'Neither the second nor the third of these must be over stressed. Above a certain size hounds become too heavy and clumsy for their work...' Regrettably, the KC Breed Standard gives a minimum height limit but not a maximum one for this breed. I see giant Deerhounds in the show ring that simply could not perform in the field. Cassels went on to say that 'We do not want little running dogs but equally we do not want great clumsy brutes'. But he appreciated handsome hounds, describing Champion Aurora of Ardkinglas, winner of both the working title or Quaich and Best-in-Show at a Championship Show, an unusual achievement for a Deerhound, as 'a most beautiful hound.' His own hound Gillaval Grad of Sorisdale (see image) won the Dava Quaich in both 1990 and again in 1991, some feat.

Writing on hunting skills, Cassels wrote: 'If the hounds were good they would get on terms with their quarry,, and the leading hound would range up alongside, balance itself, and then still at full gallop, leap for either the ear or throat hold. The force of the impact threw the quarry and broke its neck. Death was instantaneous.' It is sad that the blind prejudice of the anti-coursing lobby has led to the banning of such 'instant despatch hunting' but permitted the continuation of deer-shooting, where maimed deer can survive to suffer a long lingering painful death. With no natural enemies deer in Scotland are now so numerous as to pose a threat to their own well-being. Culling is essential. The best deer-coursers favoured hounds that practised the throat-seize (as did ancient hunters) and disliked the hindleg-seizers or 'haunchers', but no contemporary conservationist would entertain such thoughts. Any true sportsman would hold quarry both in respect and with balanced compassion. The old Highland 'deer-drive' involved Deerhounds but did not seek to test the skill of individual Deerhounds, denying breeders the ability to narrow down future breeding stock. Cassels points out that...'Almost all stalkers and keepers are bad hound handlers because they are so used to working with gundogs and terriers which work by scent that they simply do not appreciate how to use a dog that works by sight.'

Cassels writes instructively on lure-chasing, pointing out that a good coursing hound seeks to influence the line pursued by its prey whereas a lure imposes the line to be followed, baffling and 'de-training' hounds acting instinctively. Hounds only used to lures stop striving to impose their line on their prey and merely pursue it; this is a distinct disadvantage when hounds are then faced with live quarry, perhaps overseas, that can outrun them. The famed Waterloo Cup was about rewarding coursing skill not killing rates! He also gave views on the other sighthound breeds he saw at work, noting the better stamina of the Deerhound over the clear advantage of sheer pace enjoyed by the Greyhound, finding the sheer bulk of the Irish Wolfhound a hindrance in the field, admiring the Saluki but not impressed by the Borzoi (accepting it was away from the wolf-hunt).

One of my gripes about Deerhounds in the show ring is seeing hounds win despite having no lung room. It's gratifying therefore to read Cassels remembering Miss Loughrey of the famous Ross kennel lamenting the loss of spring of rib in her breed. He quotes her as stating that modern dogs were 'slab-sided'. Since then he pondered whether she was referring to bone structure or if her hounds had the vital band of muscle along the top of the ribs either side of the backbone up to and including the tips of the vertebrae. He also points out that when two animals collide at top speed and one breaks its neck, the reason that the other one (the hound) doesn't is that the Deerhound's neck is iron-hard with braced muscle. He states that muscle development can be the result of hard exercise but has a genetic aspect to it too; he found that certain lines of Deerhound passed on this ability more than others. Here is a lesson for all coursing hound breeders: breed from the right stock and you get the right result! Cassels is a sportsman worth listening to and this slim volume of his is well worth a close study.