1109

HONOURING ORIGIN - how humans can learn from the fate of dogs

By David Hancock

Where did I come from? What shaped me? Will how I originated fashion my future? In striving to answer such understandable questions, could we learn from the experience of another animal, and, if so, why not the one that has lived closest to man for perhaps a hundred millennia, the domestic dog? "Consider your origins, you were not made to live as brutes, but to follow virtue and knowledge". Those words from Divina Commedia - 'Inferno' have sadly all too often been overlooked by mankind down the centuries, with the behaviour of creatures usually referred to as 'brutes' actually shaming us with their remarkably noble behaviour; 'man the brute' is now more likely. But before we casually dismiss any pancosmetic thoughts of man's total ability to need only himself as the Owner of the Planet just think of an unpredictable freak 'accident of nature' disturbing our slumbers and who we could turn to for much-needed help. A world reliant on gadgets not gumption is vulnerable!

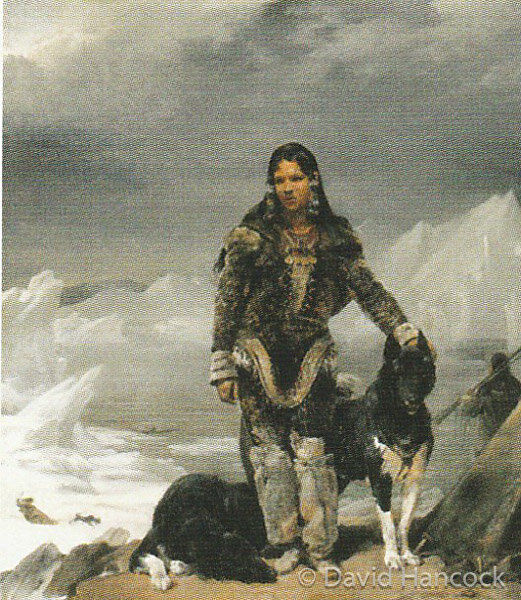

Humans of the mid-21st century, looking back, with irrational arrogance, once thought that the days when primitive man relied on dogs to fill his pot could never return. Then, without warning, came what might be termed 'Globaliteration', a catastrophic, pandemic assault on Mother Earth! The post-mortems on the global disaster of 2050 found it difficult to separate the immense impact of the substantial asteroid that hit Iran that year and whether the shock to the earth's crust caused the succession of serious earthquakes right across the Far and Middle East, some accompanied or followed by disastrous tsunamis. The loss of satellite-routed communications was total, the destruction of modern life, as we knew it, just wholescale and world-wide. Man was sent back, in so many places, to primal living. Those that best survived the breakdown of cities, the loss of communications, the serious lack of food and water, were the primitive tribes and simple rural communities that had needed so little before this global disaster, but knew how to survive such a life-changing event - supported by their dogs! Rather like primitive man across the globe before the invention of firearms, electricity and then electronics, the simple societies coped, the sophisticated societies could not. Life without mobile phones and the internet had arrived! Headline news: Man returns to his origins!

We have long forgotten the value to primitive man of dogs that could hunt animals for food and fur, lure wildfowl within arrow range, drive off dangerous wild beasts, wolves especially, and thereby provide sustenance, give protection and support, like killing vermin, just about every basic activity that man conducted. Before this calamity we could afford to keep hounds as pets or in support of our leisure interests; we had long lost the use of water-dogs and decoy-dogs but retained them as companions without a function. We still utilised dog's herding instinct, one rooted in hunting methods before their pastoral role. We still used sled-dogs but mainly for leisure not essential transport. We still used transhumance dogs to protect sheep from predators but the latter are much reduced. The invention of firearms gave man great power and minimised the value of huge protective dogs, some preserved merely as pets, but bred away from functional capability. How we failed them!

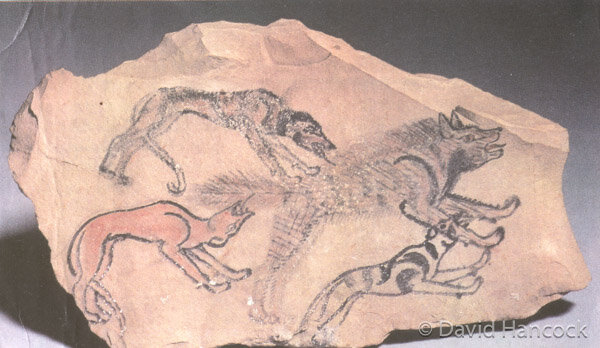

I believe the hounds came first, not of course looking like contemporary breeds of hound in conformation, but first in functional use for man. The 18th century French naturalist Buffon, I know, for one, argued that the sheepdogs came before them but I can find no logic in that. For to use sheepdogs primitive man had first to become a farmer of sorts yet man was a hunter-gatherer long, long before he became a farmer. Although I acknowledge that in some places sheep were domesticated before dog. The sheepdog's instinct for rounding up numbers of sheep or singling one out for attention almost certainly developed from the hunting style of primitive wild dog and is still practised in the wild today. But before man kept animals of his own, he needed to fill his pot with the meat of wild animals and what better ally than a tamed wild dog acting as a hound. Such a canine ally could assist man to locate game in the first place, be used to drive the game towards precipices, pits or human hunters with their primitive weapons such as spears. Subsequently these domesticated dogs were to be trained to drive selected game into specially-constructed enclosures or into cleverly-positioned nets. In due course very fast game was hunted using very fast dogs, big game was hunted with huge 'seizers' or hunting mastiffs and feathered game hunted using dogs which could either silently (like a setter) or noisily (like a bark-pointer) indicate the location of the quarry. In time the tracking dogs became specialist hounds, able to hunt boar or hare, wild asses or deer, bison or elk. In Europe, the names of the early breeds in the hunting field indicate their function: bufalbeisser (buffalo-biter), barenbeisser (bear-biter) and bullenbeisser (wild bull-biter). The bull-lurcher is their nearest contemporary equivalent; if you live near a deer park or large moor, the red deer would be their quarry. If you live near a French forest (or, here, in the Forest of Dean!) wild boar would be. Those hunters hunting boar legally with dogs, as in New Zealand and the USA, would become valued as meat farmers.

The 'beisser' group of dogs originated as heavy hounds used to assist man in the hunt for the bigger quarry: horned and hoofed beasts of great size, immensely difficult to seize and 'hold' but a supreme provider of meat. Primitive hunters would have found great benefit in having sizeable dogs to pull down such substantial quarry. This group of dogs were the canine big game hunters, of infinite value to human hunters and, unlike hounds pursuing smaller quarry, all too often sacrificed their own lives in providing a source of food to humans. Their desire to persist in the hunt has led to their being misused by man in combat with other animals and even each other. Their matchless power in the hunt has led to their being prized for their sheer size and impressive appearance. They should be prized for what they are: superb canine athletes, valuable protectors and steadfast companions, never misused to bolster shaky egos or become associated with the misguided public parading of outward belligerence. When rifle ammunition is no longer available, man will desperately need dogs capable of successfully hunting gazelle, red deer, elk and springbok.

Our increasingly town-dwelling world severely limits canine activity: for employment, exercise and therefore spiritual release. Their past service to man however should ensure that we breed them wisely, respect their basic needs and honour their heritage. They represent a quite remarkable feature of man's past needs and activities in a primitive world. They bring qualities of tolerance, restraint, controlled power and innate gentleness that we should admire. In an asteroid-devastated world they can fill the pot and sustain mankind in their hour of immense need. Seizers that could tackle an auroch deserve respect. They triumphed on land against four-footed quarry, but there were once of course dogs that triumphed on birds too. It was never impossible to snare or use arrows on wildfowl but almost impossible without talented dogs.

Hunters were ‘armed’ long before the introduction of firearms, with the spear, the bow and arrow, the boar-lance and the bolt-firing weapons to the fore. The net could also be described as a weapon, being used to capture rabbits or envelop game birds indicated by setting dogs. Before the invention of firearms, hunters were reliant on dogs which could indicate unseen game and not run-in, as well as those which could retrieve valuable bolts, especially from water, when used on wild fowl. In the late middle ages, the netting of birds was not a simple matter; dogs had to be trained to find the quarry and ‘hold’ them whilst crouching expectantly but with immense patience. Once the targeted birds were grounded by this system, the nets-men could advance with their net and cast it over both the prone dog and the almost hypnotised birds. Gamekeepers would often spread obstacles in open fields to prevent game being poached in this manner. In more modern times, poachers relied ultimately on canine skills. Humans when forced to live 'on their wits' need dogs that always have!

Finding and then catching flying prey meant locating them with ‘setting dogs’ which then lay low to allow the hunters’ net to be drawn both over them and the crouching dogs, or chiens couchant. There are many setters to this day that instinctively crouch low rather than stand and point in the classic pose. In continental Europe a draw-net or tirasse was employed; this involved the dogs crawling slowly towards the stationary birds, gradually driving the alarmed but not flight-prone birds towards the approaching nets-men. In such a way, the dogs ‘worked’ the birds into the net, rather as a well-trained collie urges sheep to move but not run. The value to the hunter, both here and on the continent, of a dog which instinctively found game on the ground, indicated its find, then almost hypnotised it into staying on the ground until a net descended on it, must have been priceless. But hunting in and over water brought different challenges.

It is therefore worth setting out the references we do have of water-dogs in medieval times. In the ancient world anyone found guilty of killing a water-dog was subject to a most severe penalty. Water-dogs came in two types of coat: long and harsh-haired or short and curly-haired. The French Barbet displays the former, the Wetterhoun of Holland and our Curly-coated Retriever the latter; the Portuguese Cao d'Agua or water-dog features both. In The Sketch Book of Jean de Tournes, published in France in 1556, the great rough water-dog is depicted, a big shaggy-headed dog swimming out to retrieve a duck from a lake. What modern sportsman has ever had to swim out to retrieve a shot duck! How many modern humans actually know how to hunt for food?

In Dr Caius's Of English Dogs of 1576, he described the Aquaticus, a dog for the duck, but blurs the water-dog with the spaniel. He does however in 1569 provide his Swiss physician friend von Gesner with an illustration of a Scottish Water Dog, retriever-like but with pendant ears. Writing in 1621, Gervase Markham recorded: "First, for the colour of the Water Dogge, all be it some which are curious in all things will ascribe more excellency to one colour than to another as the blacks to be the best and the hardier; the lyver hues swiftest in swimming...and his hairs in generall would be long and curled..." In 1591, Erasmus of Valvasone wrote a poem on hunting, which will appeal to Lagotto (the Italian waterdog) fanciers, referring to "...a rough and curly-haired breed that does not fear sun, ice, water...its head and hair resemble that of the ram, and it brings the bird back to the hunter merrily."

The invention of firearms and the subsequent improvements in the range and accuracy of guns in the shooting field brought about a large measure of redundancy in the ancient art of decoying, now rarely known about by sportsmen let alone practised. We still of course put out bird-dummies to entice feathered game like woodpigeon and duck, but it is extremely rare to come across decoy-dogs at work, despite their time-honoured employment in this field in many different countries. In Canada (with the Toller), in Holland (with the Kooikerhondje) and certainly in one place in England however, this ancient canine skill is being perpetuated. The skill of the decoy dog lies in giving the inquisitive ducks only fleeting and seemingly alluring glimpses of its progress through the reeds and undergrowth, taking great care never to frighten them or even give them cause for suspicion. Dogs can do things that humans never could!

Before the use of firearms and indeed in the days when their range was very limited, these dogs must have been enormously valuable to duck-hunters. The distinctive feature of dogs used in this way was the well-flagged tail. Their colour was usually fox-red, leading to some being referred to as fox-dogs, partly also because foxes will entice game by playful antics in a very similar vein. Clever little fox-like dogs have been used in many different countries in any number of ways in the pursuit of game: in Finland, their red-coated bark-pointer Spitz breed transfixes feathered game, and ties down hoofer quarry, by its mesmeric barking whilst awaiting the arrival of the hunters; in Japan, the russet-coated Shiba Inu was once used to flush birds for the falcon and the Tahl-tan Indians in British Columbia hunted bear, lynx and porcupine with their little black bear-dogs, which were often mistaken for foxes.

In Canada, probably taken there by European colonists, there is the Toller or Nova Scotia Duck-Tolling Retriever, a golden-red medium-sized dog with the distinct look of our Golden Retriever about it. This Canadian dog is about 20" at the shoulder with a compact muscular build, alert, agile and determined, a strong swimmer, easy to train and a natural retriever. To be a successful duck-toller, such a dog needs a playful nature, a strong desire to retrieve and a heavily-feathered tail that is in constant motion. The skill of the hunter lies in throwing the stick for the dog the right distance at the right moment so that the ducks are not frightened away by the menace of an advancing dog, but made curious by the enticing waving of its bushy tail. The dog makes a normal retrieve of the stick but does so in a playful manner with plenty of tail-wagging. This decoy dog does not entice the birds by deliberately frolicking about, as foxes have been seen to, but is used essentially as a retriever of sticks. This playful retrieve however does lure the duck within range of the arrow, net or similar simple weapon. This ability does not lend itself to hunters without canine support!

If sporting breeds are to be there ready for unidentified future calamities, there has to be a planned renaissance, not an abrogation of responsibility for breeds we specifically bred and developed over several centuries to assist us in the sporting field. It would be a major step forward if breed clubs took up this challenge, although I suspect that challenge certificates have more appeal for them. Just as the United Kennel Club in the United States fathers a wide range of field activity for dogs, so too could our own Kennel Club (KC), extending their field trial and agility interest. Sporting organisations too could cut their losses and diversify their sporting agenda, in the interests of the hounds alone, if only to have the canine ingredients of a rebirth one day, should field sports regain favour. To neglect the best interests of the dogs would be shameful. Positive thinking is called for, not intellectual collapse. The so-called 'civilised world' is just not made to cope with global catastrophes and all that embraces, but dogs are!

Throughout our social history as a nation, changing social attitudes have influenced our use of dogs in the name of sport, rather than survival. Few social attitudes have been shaped by global disaster! Barbaric activities like badger, bear and bull-baiting, rat-killing competitions and dog fighting contests have rightly been outlawed. Nevertheless, we still prize and perpetuate that canine gladiator, the Bull Terrier, even if some legislators retain the view that once a fighter always a fighter. This irrational approach doesn't extend however to Zulus, once a superlative martial race or the Vikings, as my peace-loving Danish friends point out to me, with some amusement. The spirit behind the trail-hound and Whippet racing, the Bloodhound packs which hunt a human trail, lure-chasing with Irish Wolfhounds and even nocturnal rat-catching in a maggot-factory, as the late and great terrier-breeder/writer, Brian Plummer, recommended, provides such encouragement for the future of sporting dogs. Perhaps, sadly, the single-issue lobbyists have them too in their sights, as they now have trail-hounds. Zealots defending their version of the 'natural world' forget that dog is part of that world. Vermin-control without manufactured poisons and weapons comes down to a canine monopoly!

At a time in the world of dogs, when cross-breeds and mongrels can be insured at a lower premium than pure-bred dogs, on health grounds not marketplace value, there is a need to take stock. Insurance assessors are no fools. Pure-breeding is the main basis of perpetuating breeds and is therefore both advisable and admirable when things are going well in any breed. But when breeds produce dogs which have a reduced life span and fall prey to every ailment available, things clearly are not going well. Dogs bred purely for appearance and not function will always be vulnerable to man's greed, vanity and, sadly, his lack of moral values. Nearly a century ago, CR Acton wrote "The Foxhound of the Future", only 120 pages long but full of good sense. One of the chapters he called 'Racial Fatigue', in which he argued that: "...inbreeding contributes nothing new to a line, but may intensify the determining strength of defects". His advocacy of genetic principles for breeding rather than subjective hunches provoked hostility from more than one Master of Foxhounds, who counter-argued that experience was of more value than professors. I would have thought that knowledge was the key. What merit is there in breeding litter after litter of low-standard dogs? Or indeed human beings with inheritable conditions; dog research can benefit people!

The veterinary profession, and geneticists more generally, know that inbreeding is often accompanied by an increase in defects: smaller litter sizes, increased post-natal mortality, general lessening of body size, lower reproductive performance, less robustness and behavioural problems. It is not inbreeding per se which brings about these defects but the presence of deleterious recessive genes which are being carried in the stock. Experience alone will not locate the presence of such genes, knowledge or qualified advice is needed too. Close-breeding in some Caribbean groups of people or consanguineous marriages in Asia have shown humans the perils created by such social practices. Inherited defects are cruel inflictions. Breeds and tribes can learn from one another!

Seventy years ago, US veterinary surgeon Leon Whitney found better disease resistance in his crosses between two pedigree breeds. A study by Scott and Fuller in 1964 indicated that the high puppy mortality characteristic of matings within a breed was greatly reduced when two different breeds were crossed. A study by Rehfeld in 1970 showed that the frequency of neonatal death in pure-bred Beagles increased with the degree of inbreeding. Twenty years ago, a study by four distinguished Ontario Veterinary College scientists concluded that "The advantages of hybrid vigour in a pure-bred line could be realised in a carefully controlled breeding programme making use of out-crosses." Who listens when experts like this speak? But humans have demonstrated the value of mixed races in sport, as the Olympics and international contests illustrate every few years. Mixed race sporting dogs also excel as Korthals Griffon, Sprockers (a Cocker-Springer Spaniel blend) and lurchers demonstrate so powerfully. But it is better when planned and not derided!

Far too many pedigree dog breeders merely perpetuate the past, rather than improving on it. Their irrational stance on colour exemplifies their intransigence. The great setter man Laverack believed that a change of colour was as good as a change of blood. For any breed to favour one colour to the detriment of others can limit the genetic base of the breed. In a number of breeds of course the coat colour is the breed. But where a breed starts off with a variety of colours and then ends up favouring only one or two is an enormous loss. Breeding on colour ahead of opting for virility is unwise. We have a duty of care towards subject creatures. We have seen the benefits in humans - or rather lessons of dog breeders have value for humankind!

Distinguished breeders like Brough in Bloodhounds, Millais in Basset Hounds, Graham in Irish Wolfhounds, the Martinez brothers in Dogos Argentino, Laverack in English Setters and Edwardes in Sealyham Terriers had the skill and the vision to employ outside blood. Few pedigree breeds today were evolved without a combination of blood from identified breed-types. There are of course talented breeders of KC-registered pure-bred dogs producing excellent specimens and we all admire their stock and their skill. It is when things are going wrong that a radical rethink is demanded. Breed Councils, at least in the eyes of the KC, head up the recognised breeds. But do their agendas ever contain items like Breed Vigour, Longevity or Loss of Original Type? Most breed clubs are prepared to discuss judging and showing ad infinitum but rarely consider 'the state of the breed'. A breed survey initiated by the KC to examine the state of each breed would have enormous merit. No organisation claiming the mandate of 'the improvement of dogs', as the KC does, can overlook the welfare of breeds suffering from racial fatigue. It is a duty!

No working shepherd, professional terrier-man, huntsman, cattle rancher or shooting man of the 19th century would have tolerated weedy dogs without a function. That is how the splendid breeds we enjoy today came down to us. We insult the memory and betray the work of all those pioneer-breeders who bequeathed such dogs to us when we put breed purity ahead of breed vigour and breed robustness. Out-crossing, or cross-breeding, is no magic answer but it was the resort of many extremely knowledgeable truly experienced breeders in times past. It should not be unthinkable today. We have, wittingly, undermined the nature of the domestic dog.

We are guilty of perpetuating races and breeds which, because the pure blood has been illogically treasured or 'allowed to wag the dog', lack robustness, vigour and a healthy genotype. Worship of the phenotype, or what the dog looks like, ahead of all ethical factors, has led to breeds becoming prettier but no longer, to use an old-fashioned phrase, hale and hearty. Short-lived dogs may make dog-traders richer, when replacement pets are needed more regularly, but their premature deaths do not exactly enrich the precious man-dog relationship. Pet cemeteries should be full of old dogs not young ones. When that asteroid hits Mother Earth those of us left will need to benefit from dogs' sheer versatility and carefully-perpetuated instincts - but such functional skills need to be bred for not bred out! Why not realise and accept that by quietly preparing for calamities, however unlikely, we are so much more likely to survive and rebuild what we once had - do we not owe that to the next generation?

For a nation that has given the world a score of distinguished sporting

breeds, many of them preferred to the local breeds on sheer merit, we

must now work to ensure that all the dedicated work of our forefathers is

not thrown away - especially if the stars predict an asteroid hitting Mother

Earth 'sometime in the future'. In many emergencies we can be saved by

our dogs; there never will be contingency plans to offset or survive a

global catastrophe but by ensuring that our age-old sporting dogs can still

function, whether as crouching game-finders, hunting mastiffs, water

-dogs, decoy-dogs, 'dogs for the net' in hawking, bark-pointers, haulage

dogs, hounds that hunt by scent, hounds that hunt by speed or just smaller

dogs to kill vermin, we would have many quite simple ways of ensuring

that some of us survive! As the American philosopher, Eric Hoffer once wrote: "Originality is deliberate and forced, and partakes of the nature of a protest." I now protest...