1112

BREEDING A BETTER BULLMASTIFF

By David Hancock

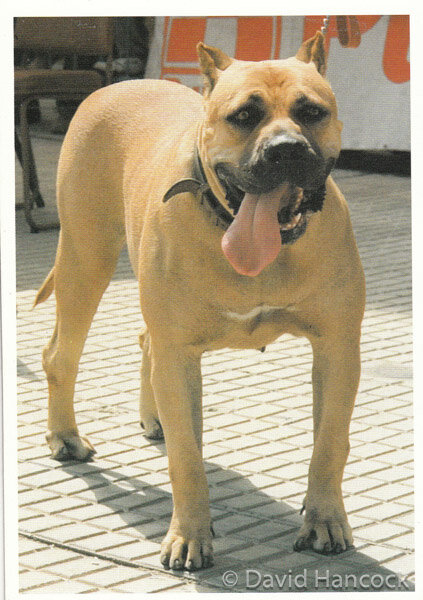

I have never bred, exhibited or judged Bullmastiffs but was a committed owner for many years, serving as a committee member of a breed club and speaking at seminars when invited. When choosing my own stock I always tried really hard to make myself familiar with the Breed Standard. All the time I came across those who do all of these three functions - breeding, showing, judging - but sadly not only did not understand the standard but were unaware of its stipulations. How can any breed prosper against that background? I groan when I hear the Bullmastiff described as a 'head breed'; when is it going to be agreed what the head of the Bullmastiff should actually be like? There are breeds recognised far more recently than the Bullmastiff, and from a bigger mix of ancestor-breeds, that are exhibited with a common head structure and uniform type. All these Bullmastiff seminars and still no agreement on type! In a breed representing a blend of Mastiff and Bulldog blood, it is vital that these two principal ancestor breeds do not separately come through too strongly and change type in the breed. The Bullmastiff has been a breed in its own right long enough to have established its own precise breed type, as drawn up in the word picture of the breed, the Breed Standard. These words apply equally to the Boerboel, the Neopolitan Mastiff, the Cane Corso and the Dogue de Bordeaux; each of these too can become far too bulldoggy, as this strong ancestral trait manifests itself in some litters. Sadly, some mistaken breed fanciers seem to favour this type, it appeals to their apparent need to have a visibly-pugnacious dog rather than one true to its own breed title. Breed identity matters and breed promotion must always rest on breed type, both in temperament and physique.

I have rarely read a truly definitive article on what constitutes 'type' in any pure-bred breed of dog, so how on earth can judges spot it or indeed breeders breed for it? Oh, lots of writers have repeated sections of the Breed Standard or listed breed points as exemplars of breed type. But breed points can vary in value to the breed; type in any breed is only there when the essential breed points are displayed. Every breed needs type to define its identity. The word 'type' itself shouldn't be left to each individual to define, it needs one agreed meaning. My definition would be on these lines: Type is the manifestation in a breed of those particular innate physical and mental characteristics that, without exaggeration, distinguish the traditional form that a breed should take. In using these words I am seeking to preserve and perpetuate the character and conformation that was stabilised and then established when distinct breeds evolved – nearly always in pursuit of a specific function. I groan when I read show critiques, often by experienced judges, when they praise virtues in exhibits which are not embraced by the Breed Standard. That surely can only lead to the eroding of breed-type. You only have to look around the contemporary show rings to see that different Bullmastiff breeders are seeking noticeably different varieties of the breed.

So what constitutes true type in the breed of Bullmastiff? No breed standard tells you what is essential in each breed; it is for the Breed Council perhaps to set out the breed's stall. Too difficult to obtain agreement, the pessimists would claim. It varies from kennel to kennel, I was informed by one prominent breeder; so much for breed type! It's all in the Breed Standard, advised another breed elder; but is it? Why does the Standard not state that the nose of a Bullmastiff should be black? The Standard tells us that the ears should be 'folded back', but they are not actually desired to be so. What really makes the Bullmastiff the breed that it is? How beneficial it would be, before any all-rounder judged the breed for that judge to be handed, not just the Breed Standard, but those essential points which distinguishes the breed of Bullmastiff from say the Dogue de Bordeaux, the Mastiff, the Perro de Presa Canario or the Boerboel. All had a common origin yet have distinct differences, differences which really matter. Is a fawn Boerboel with a full tail not easily confused with a Bullmastiff? Is a brindle Mastiff, 26" at the shoulder, not very, very similar to a Bullmastiff? I have seen a Dogue de Bordeaux, with a black nose, looking very much like a Bullmastiff with the same degree of 'wrinkle'. Would a fawn Canary Dog without cropped ears not look like a Bullmastiff?

If the Bullmastiff really is, in that damaging expression, a 'head breed', which of the different heads being presented to show ring judges at the moment, is the one most representative of the breed? If you read 'Exchange and Mart' magazine or attend unofficial bull-breeds' shows or rallies, you will know that Bullmastiffs are being crossed with Dogues de Bordeaux, Canary Dogs, Ridgebacks and Bulldogs. Bullmastiff devotees may not like it, but it is happening. Unless essential breed type is established for the Bullmastiff, breeders of these hybrids can pass off their pups as pure-bred Bullmastiffs; plenty of genuine Bullmastiff pups are sold without papers. The Breed Standard of the Bullmastiff does not mention the word 'mask' and does not stipulate a black nose. It could be argued that a black muzzle brings a black nose with it and that dark markings around the eyes constitute a mask. But why not spell it out and reduce the likelihood of arguments? If the black muzzle is essential, why isn't the black mask too? If the coat should be pure and clear in colour, how can two-tone coated dogs become champions? As they have. If the head typifies the breed, how can dogs win with muzzles far less than one third of the distance from the centre of the occiput to the tip of the nose? The words of the Breed Standard don't always protect the breed from its own breeders.

The Bullmastiff is expected to have well-boned forelegs but not well-boned hindlegs, yet be symmetrical in general appearance. Show critiques make constant mention of 'great bone' but the Standard doesn't. A foreign judge at a 2001 championship show placed a Bullmastiff first in Group 2, stressing its 'outstanding bone'. Was he judging shire horses or a breed designed to be active? Another judge's critique in February 2001 stated that: "I found so many which had ultra-short muzzles; a number with over-wrinkled skulls and quite a few with loose flews." There are clearly Bullmastiffs being entered for major shows which defy their own Breed Standard. Do their owners actually know this to be the case? One Bullmastiff kennel seems to favour the Boxer-chin and has champions made up carrying this feature. Surely that is untypical? There were several exhibits at the British Bullmastiff League Spring 2001 show with lurcher tails and brown not fawn coats. No doubt they were bred from! The breed standard has its faults but is quite specific on coat-colour and tail requirements. The judge at the Manchester 2000 show wrote: "This year marks the 75th anniversary of the KC recognition of the Bullmastiff as a pure-bred dog, yet after all this time there is still such a wide variation in type. In some of the classes I was hard pressed to find two of a kind." At the 2001 World Dog Show, a much younger breed, the American Staffordshire Terrier, attracted an entry which looked as though they had all come out of the same dam, so even was their appearance. Is it just a British inability to breed for type?

One Breed Council has pioneered a breed survey scheme and tries to grade breeding stock. If the breed of Bullmastiff is to maintain essential type, perpetuate the classic breed we inherited and not go forward as 'any variety mastiff-type', there is work to be done. The Breed Council could for example set out the ten essential points which embrace breed-type and persuade clubs to put up prizes for the entrant best encapsulating breed-type. Ah, the destructively-minded will claim: Surely the best dogs at the show must encapsulate breed-type. Nice try! But what if the dogs are judged on 'outstanding bone', have brown coats and lurcher tails? It is vitally important, not just for the Bullmastiff - under consideration here - but in every Mastiff breed, for the essential elements of that breed, what actually makes it a breed in its own right, to be clearly laid out and then bred for. Bloodhoundy Mastiffs are just as untypical as bulldoggy Bullmastiffs!

If you judge the condition of the breed of Bullmastiff on the annual registration figures, the number of entries at championship shows and the membership of the six breed clubs or societies, then you could be forgiven for thinking that it is declining. That is however not the collection of yardsticks on which to judge the health of any breed of pure-bred dog. Those familiar with the breed of German Shepherd Dog over the last fifty years will quickly confirm that numerical strength doesn't reflect the state of the breed. There will always be those, of course, who consider the best in any sphere to have been in the past. Such nostalgists however do not contribute much to the future. But true lovers of any breed of dog surely want to leave it in better shape than when they found it. Perhaps the biggest threats to the well-being of any breed come from such diverse factors as: ignorance or ill-founded complacency; money-making at the expense of soundness in the dogs; personality clashes within the breed (dog-breeding has more than its fair share of inadequate personalities) and incompetent judging, so that the wrong dogs win - and get bred from. These factors are threats to the future of any breed and, sadly, they tend to be constant by nature, posing an even bigger longer-lasting threat. Myths too seem to be self-perpetuating in the world of pedigree dogs, with the myth that experience alone brings knowledge being the most dangerous. Thirty years' experience can mean one year's experience repeated thirty times! I ran a Rare Breeds Centre for farm livestock for many years; I never found the most experienced breeders to be the most knowledgeable. Some were amazingly ignorant of the science of breeding.

Any breeder can 'get lucky' and produce a really good dog which wins well. A few years ago a Bullmastiff won Crufts, with a 5-generation pedigree which indicated 59 different ancestors out of 62. And breeders queued up to take their precious bitches to him! How could they possibly know what kind of progeny he would throw? Can you imagine racehorses being bred in such a fashion? Of course, if you breed 100 pups then statistically you are likely to get more good dogs than if you breed 10. But why not reduce the odds? Genes work in a random way; that makes the breeding of family to family more important than breeding Champion A to Champion B. Breeding a lot of litters can only have value when a breeder produces a lot of good litters. Any fool can produce puppies; regrettably some fools become rich fools, although their bank manager might dispute the noun! Who wants to depart this life with the epitaph: He bred a lot of dogs - none of them any good? At a breed club show a year or so ago, there were exhibitors there only too willing to display their ignorance and limitations by entering Bullmastiffs that had: Boxer chins, lurcher tails, brown not fawn coats, muzzles shorter than the breed standard allows, cow-hocks, barrel-hocks, upright shoulders - often accompanied by short upper arms, dippy backs, a Foxhound tail-carriage and quite awful movement. Ignorance is bliss - but never in breeding plans.

Good breeders might well argue that a bad breeder can still sell his pups, and that is irrefutable. But what honourable person, who really cares about a breed, wants to produce poor quality pups? We live in an age which features the Sales Descriptions and Sale of Goods Acts; Trading Standards Officers will tell you that the consumer is going to the law at a rate never seen before, especially over product quality. It has to be asked: What are those in charge of pure-bred dogs doing to prevent their over-production? I know of no scheme which effectively curtails the excessive breeding in any breed of dog. This does not reflect well on those who have power. It certainly does not help the good souls involved in rescue. Money-making in a breed is always at the expense of a breed. The over-use of one sire, the over-production of puppies, the over-breeding of one bitch, breeding from dogs carrying serious faults--each in their own way demean and degrade the breed. One day soon the Kennel Club will insist that before a litter can be registered, the parents must have health clearances. One day in the future the Kennel Club will decline to register a breed club unless it has a comprehensive breed rescue scheme, a breed health scheme based on a compulsory survey and a mandatory code of ethics. Why not prepare for the future?

The petty jealousies, character assassinations and personality clashes in the world of pedigree dogs never ceases to amaze (and disappoint) me. If only people could be as magnanimous as their dogs! Such failings, coupled with kennel blindness and too-ruthless a desire to win challenge certificates, can undermine a breed. Clubs run by cliques are a distinct threat to a breed too. Bullmastiffs are very honest dogs; they deserve supporters who are, above all, honest too. Honesty means acknowledging when you are not acting in the best interests of the breed, that you may not have the knowledge to be a judge, that you need to expand on your knowledge of breeding, and, especially, that you can learn more by listening than talking.

If Bullmastiffs are to be produced which all resemble one breed, which live a long time, move soundly and have few breed-disposed inheritable defects, there is hard work ahead. There are far too many 'in the breed' who claim to love the breed but do little to improve it and seem to care little about breed welfare. Difficult for honourable individuals to counter such contemptible conduct, of course, but it is hardly brave to do nothing. Far too much shameful behaviour and too many harmful practices are silently condoned by good people in every breed; turning the other cheek is not brave. Dishonesty demands exposure. Time and time again, Bullmastiff devotees mention and revere the pioneer breeder Moseley. They proudly claim heritage for their dogs from the gamekeepers' night-dogs. Firstly, Moseley was a cheat and a scoundrel; his dogs showed no signs of 40% Bulldog blood and, genetically, his breeding formula is nonsense. But he did breed some good dogs. Not one of them displayed a short muzzle, yet founded the breed! Secondly, the gamekeepers' night-dogs were often the Mastiffs of those times, but more like the traditional Mastiff than the Mastiff of today's show rings. The modern Mastiff was recreated in the late 19th century using the blood of the Tibetan Mastiff (imported from unknown breeding), the Alpine Mastiff (the Smooth St Bernard, but carrying the long-haired genes) and cross-bred Great Danes.

These influences are in the Bullmastiff gene pool. Small wonder that a freak mainly-white or long-haired Bullmastiff crops up in litters exceptionally. It doesn't need outside blood or a misalliance to produce such anomalies. But the Bulldog blood is the strongest influence to be countered. It will ruin the breed of Bullmastiff if unskilled breeders persist in producing short-muzzled dogs. It is a feature which exaggerates itself; the short muzzle is genetically dominant. Do we want Pug-mastiffs or Bullmastiffs? Where then is the breed heading? At worst it could be heading for a gene pool in which inheritable defects are being concentrated and in which the short muzzle is being enshrined. Bullmastiffs are relatively short-lived and this needs attention too. If you throw in unacceptably poor movement, then there is an enormous amount to be done within the breed. But by whom? Breed clubs? The Breed Council? By a group of enlightened individuals forming a new breed club? The future of the breed is very much in the hands of present-day breeders, judges and club committees. I do hope that Bullmastiff fanciers of the future will be proud of them. There are in my view a good number of quality young dogs in the show ring in the early years of this new millennium and impressive new breeders too.

Finally, are the views expressed here highly individual ones? Here are the words of others on the breed (a decade or two later the descendants of these dogs are being bred from):

"Each time I judge this breed in the UK, the quality deteriorates...the larger proportion of both dogs and bitches were appalling in movement." Terry Thorn, top UK judge, July 2001.

"Over the years a variety of types and sizes have crept into the breed, which is a pity...Movement overall is not good..." Jean Lanning, leading UK judge, October 1998.

"Decisions on the majority of placings were made difficult by virtue of the enormous variety, in so many aspects of the breed, which have appeared in recent years." Ann Arch, leading UK judge, Breed Show, December 2000.

"I have long been intrigued by the seemingly endless variety of Bullmastiff heads presented to me inside and outside the show ring." Robert Cole, international expert on conformation, December 1997.

"This year marks the 75th anniversary of the KC recognition of the Bullmastiff as a pure breed. Yet after all this time there is still such a wide variation in type." Bill Harris, veteran breeder of Bullmastiffs, Manchester Show critique, 2000.

"...I was rather sad to see that there appeared to be as many problems in the breed as there are in Mastiffs. It was quite hard to find anything with all the essentials I was looking for, to find a typical head allied to a good body..." Betty Baxter, top Mastiff judge, February 2001 (judging Bullmastiffs).

The current crop of Bullmastiffs come from such stock! Are all these knowledgeable people, quite separately, all wrong? Nearly three hundred years ago, Jonathan Swift, the Anglo-Irish poet and satirist, wrote:

"They never would hear, But turn the deaf ear,

As a matter they had no concern in."

The state of the breed, the condition of the Bullmastiff, is surely of concern to every genuine lover of the breed. Turning a deaf ear is the coward's way out. This magnificent breed will not thrive unless those 'in charge of' the breed take positive steps to safeguard its future. It is no solace to hear that other breeds have bigger problems. Each breed is primarily the responsibility of its own fanciers, mainly through its various breed clubs. It should be no chore to look after your own breed. Actions speak louder than words; these are mere words.