1117

WHY BREED FOR FUNCTION?

By David Hancock

In ancient times, it was perhaps easier to ascertain why dogs were bred. With the threat from wolves to domesticated animals, no firearms to kill game from a distance, roving bands of robbers and freezing nights in poorly-heated dwellings, it is easy to justify how flock-guarding, arrow-retrieving, deer-catching, house-protecting and warmth-providing dogs could be valued and then perpetuated. But the biggest single reason for the remarkable development of so many breeds was man's love of sport, from the Greeks in classical times to medieval Bavaria and beyond. Sportsmen in country areas all over Europe have long taken their pursuit of game extremely seriously. Duke Ulrich of Wurttemburg made an order in 1517 which read: "Anybody, whoever it may be, met with a gun, crossbow or similar weapon in the duke's forests and hunting grounds, in woods or fields or any place where game may be about, away from public roads, or is seen to move in a suspicious way, even though he is not in the process of shooting, will have his eyes gouged out." In the same year, the zealous duke had a poacher sewn alive into the skin of a stag and coursed by his hounds. No doubt he had just as serious an attitude to the selective breeding, for function, of his sporting dogs.

This rather serious approach to hunting and shooting led to enormous and enormously-varied bags being accounted for each year. In one year, 1669, the following were offered for sale from the Elector's store in Dresden old town: 861 red deer, 616 wild boar, 646 hares, 751 partridges, 65 woodcock, 20 Indian geese, 4 swans, 15 bears, 74 wolves, 15 lynxes, 170 foxes, 55 badgers, 17 beavers, 27 otters and 13 squirrels. Could such a total have been achieved without the help of dogs? Could this have been achieved without the help of dogs bred for a specific purpose? The combination of a passion for hunting by noblemen in Europe and the wide range of prey led to the development of most of our contemporary sporting dogs: hounds, setters and pointers, with functional excellence being the sole criterion; no sign of any obsession with bend of stifle, level topline or length of ear. When my eye is attracted to a statuesque, over-furnished and purposeless, unmotivated English Setter posing in a gundog class at a conformation show, I, almost in sadness, ponder the rich heritage behind this splendid breed. I recall the superb field dogs run by Dr JB Maurice from his "Downsman" kennel; the extraordinary field trial record of William Humphrey and his "Windem" line of Llewellins. Llewellin bred for function, as did fellow setter-breeder Laverack - with his handsome yet functional dogs - then think back still further to the chien d'oysel of medieval times; if they couldn't perform, they didn't get bred from.

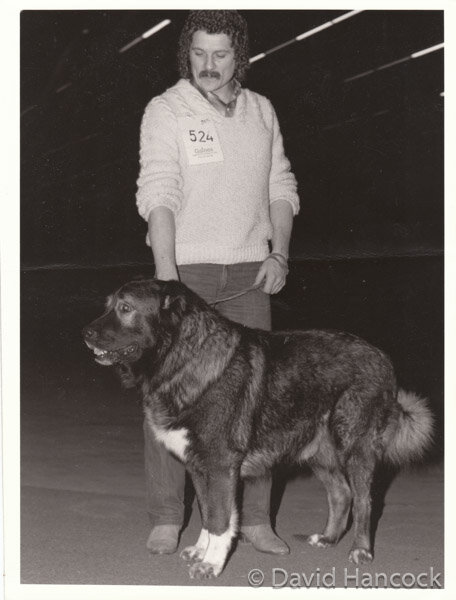

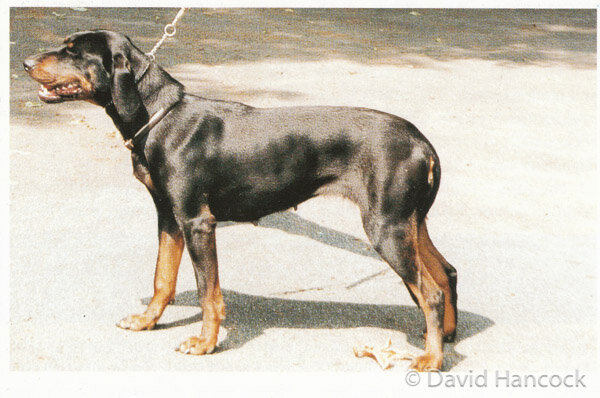

Dogs bred for a particular function, not surprisingly tend to resemble each other. I can remember seeing an impressive, solid-coloured, red-gold Langhaar for the first time - thinking from a distance that it was an Irish Setter. I recall too the admirable Small Munsterlanders I saw in Westphalia over half a century ago - so much like the Llewellins in their working style. Before we bred for show ring appearance, it was easy to see immediate physical likenesses between the German stable dogs, the working Pinschers and Schnauzers and our own equivalents like the Irish, Kerry Blue and Lakeland Terriers. At World Dog Shows the Russian Black Terrier is easily confused with a Giant Schnauzer, a Beauceron with a Transylvanian Hound, a Greek Hound with a Canaan Dog, a Karst from the Balkans with a Caucasian Owtcharka, a Maremma with a Tatra Mountain Dog - the last four breeds evolved from the same function - flock protecting. In the Middle Ages, the big game hunting dogs looked very similar across Europe - as the Englische Dogge and the Deutsche Dogge demonstrated in depictions of them by famous artists. Their descendants, the Mastiff and the Great Dane look very different and are bred to very different criteria. In similar vein, the modern Briard should never be confusable with say an Afghan Hound, in their original form neither needed excessive coat length.

Should we be prepared and even eager to breed dogs that are still capable of carrying out their original function even if they will never be required to do so? If we do not, we could end up producing handsome but useless, glamorous but quite boring, and quite standardized/similar dogs: Vizslas resembling ridgeless Rhodesian Ridgebacks, Soft-coated Wheaten Terriers in the mould of the Bouvier des Flandres, Boston Terriers rather like French Bulldogs, Sloughis like Azawakhs, Welsh Terriers easily confused with a big Lakeland Terrier and Japanese Spitz easily mistaken for a Volpino. Does this matter as long as such dogs are healthy? Only if you value breeds and can identify breed points ahead of regrettable exaggerations. Breed differences should not become blurred in the all-consuming world of the show dog. Breeds need to be individual not merely lip-service to some vague concept of a breed's identity.

In that way we keep faith with those we record reverently in their breed histories. In that way we honour the heritage of the precious breeds we have the privilege of owning in our lifetime. Just as they were handed down to us, we in turn have to hand them down to those who come after us. We should be able to do so both with a clear conscience and immense inner satisfaction not with silent regret and concealed embarrassment.

When is a breed not a breed? Some might argue that to be truly a breed, then kennel club recognition somewhere in the world is a prerequisite. But this would deny us a rich array of terrier and hound breeds that breed true to type and bear acceptable breed titles, but have never needed kennel club recognition. Fell Terriers and Harriers are more familiar names than Xoloitzcuintlis and Chinooks; the former have no kennel club recognition here, the latter two do have such recognition abroad and no doubt will soon feature here and seek it. Defining a breed with appropriate words is not entirely straightforward. My own working definition would be: a race of dogs that has been genetically isolated so that each member of that race resembles the others from the same breeding. I don't believe that kennel club recognition is essential for a breed to be regarded as a breed. Breeders of hunting packhounds in the world and sporting terriers here would probably support that view. Some countries have been very forthcoming in obtaining official recognition for their native breeds, the Swiss, for example, over their many hound breeds, all unknown here. But whilst there are six breeds of Dachshund, there is not, unlike the Belgian and Dutch Shepherd Dog, more than one breed of German Shepherd Dog. (But some cannot tell apart the BSD (Groenendael) and a black GSD).

Yet the old German breed displayed as many coat varieties as its western neighbours and possessed too a pure white sheepdog, as did so many other countries. A wire-haired, shaggy-haired, smooth-coated or whole white German Shepherd Dog might not get official approval nowadays, but the gene pool of the German herding dog included those varieties. Similarly there have been examples of rough-haired and long-haired, or Wheeler, Whippets, and, whilst many have alleged out-crosses to achieve these coats, the Whippet gene pool may well embrace them. There was uproar a few years ago when a mainly white Bullmastiff cropped up in an American pure-bred litter. There was concern too when piebald Mastiffs appeared both in Australia and America. There were allegations of a misalliance with an American Bulldog or even a St Bernard. But I cannot think why; mainly white Mastiffs were once quite common in Britain and that is where the genes come from. The distinguished vet and author Frank Townend Barton once found that his pure-bred Bloodhounds produced a whole white offspring, not an albino. He disposed of it and always regretted losing such genetic diversity. Throwbacks can be valuable breeding material.

Some distinguished breeds owe their existence to a gifted breeder who has worked to a plan and achieved his goal, such as Korthals with his Griffon pointer and the Martinez brothers with the Dogo Argentino. But I am wary of tiny gene pools. The Chinook is a sled dog breed derived from one outstanding dog. It demands great breeding skill to continue such a breed successfully. The Albanian Wolfhound on the other hand may never be a recognised breed and doesn't always breed true to type, but has all the virility of our lurchers. I do hope we do not lose the genes of the Dutch Steenbrak and the German Steinbracke, important features in the development of hound breeds in western Europe. This is one of the dilemmas in the world of dogs in the 21st century: do we value and perpetuate old breeds carrying valuable breeding material or let them fade away? Do we promote the recently developed Moscow Toy Terrier or insist on conserving the Iceland Farm Dog, which has survived centuries in a harsh environment? Do we ignore our native Harrier and patronise the Spanish Hound of a comparable type? Do we favour the Florida Cow Dog, now breeding to a set type, or the German Sauerland Hound of ancient lineage? Should we conserve the Austrian wire-haired Styrian Mountain Hound, which has proved its worth to man, or the long-haired 'sport' of the Chinese Shar Pei on display at a past Crufts?

Some breeds will undoubtedly disappear unless a group of determined fanciers come together and take charge. Even usually turgid-thinking kennel clubs have now accepted they have a role in this, especially where native breeds are concerned. The German Short-haired Pointer is a common sight at shows and in the field nowadays in Britain. But when working in Germany, as indicated earlier, I have always been more impressed by the Langhaar and the Stichelhaar than the Kurzhaar. This was also true of the Small Munsterlander, which always impressed me more than the larger variety, but has never attracted British interest. Promoting a particular breed has often had a 'hit or miss' element to it. Look at some of the KC-agreed breed histories if you doubt the credibility of my words! Comparable inventiveness has been responsible for the creation of some actual breeds. Are the Spanish Galgo and the Hungarian Magyar Agar really separate breeds from our Greyhound? Does the ear carriage difference between the Norwich and Norfolk Terriers justify their distinct classification as separate breeds?

Why does there have to be speculation over whether a dog rescued by British forces in Afghanistan is a Maremma or a Kangal Dog? Why can't it be an Afghan breed-type for which breed status has never been sought? Our own Victorian writers found difficulty in not regarding foreign breeds as having a quite separate development from ours. They even copied each other in debating whether our ancient water-dog, the Curly-coated Retriever, was a Poodle-Whiptail cross, and had little chance of understanding the origin of overseas breeds against that sort of ill-informed reasoning. And, to be fair to them, it is easy to think of the Gonczy Polski when you first see a Slovene Mountain Hound or a British or Irish setter breed when you first see a Langhaar or a Drentse Patrijshond. But such similarities should serve to remind us that breeds developed from function. Function often decided the type of coat, the stature, the head shape, the length of leg and therefore the appearance of the dog and the identity of the breed. Breed identity matters despite origin and ancestry being overplayed by breed zealots and breed history unwisely romanticised. But in the beginning, function gave us the breed-type and if we wish to preserve and perpetuate a breed, we really must respect its founding function - or we lose the breed!