1126

DEPICTING ITALIAN MASTIFFS

By David Hancock

In The Times on Saturday the 17th of March 2018, in their series under the heading Collecting, their arts correspondent Huon Mallalieu described a painting by Barbieri in his piece entitled Country houses can still hold hidden gems. This depiction, he alleged, was of 'a cane corso, ancestor of today's Italian mastiff' going on to state that "the breed was described by the count's (i.e. Count Filippo Maria Aldrovandi, a patron of Guercino, another name for Barbieri) naturalist kinsman, Ulisse Aldrovandi, as large-pawed, straight-legged, comely-chested and 'such as breaths fire from a wide nostril what time he fills the woods with his bark'". Mallalieu claims that this depicted dog fits this description despite the fact that its legs are short and bandy, opining that this latter feature, may have therefore been of the runt of its litter! When I want information on art I go to an art expert; I therefore expect an art expert, when he wants information on breeds of dog to go to an expert on just that! He failed to mention that the Cane Corso, like the Neapolitan Mastiff, is an extant breed of dog recognised by kennel clubs and shown at World Dog Shows as such and that this portrayal is nothing like this breed. It resembles, if anything, a corgi-bulldog cross! He also didn't seem to realise that short bent legs, like short squashed muzzles, are genetic aberrations, despite being embodied in several modern breeds, regrettably. Misidentification of breeds of dog by art historians are sadly not exactly new.

The two mastiff breeds of Italy, the Neapolitan and the Cane Corso, undoubtedly share a recent common origin and can be confused even when side by side. In summary, the Neapolitan is looser-skinned, more heavily wrinkled, especially around the head and neck, is taller and heavier and has the larger skull. Piero Scanziani, a respected breeder and writer of the 1950s, however, linked the word 'Corso' not with Corsica, as some do, but an old Italian word for robust or strong; I would be inclined to link this word with the Latin 'coercere', to restrain or hold back, for that is what all the holding dogs do. Scanziani considered this breed title another name for the Neapolitan Mastiff. But now, probably correctly, we have two quite separate breeds, recognised as such by the FCI. I believe that in southern Italy there still can be found fanciers who prefer shorter-legged Neapolitans, similar to the low-slung mastini of Zaccaro, a type associated with Naples half a century ago. About that time, in Campania, near Lake Patria, Claudio Cocchia maintained a kennel of white mastini. This was more the 'dirty' white found for example in the Soft-coated Wheaten Terrier, than the pure white of, say, the Bull Terrier. But white does feature in the modified brachycephalic breeds, as the Bulldog and the Boxer demonstrate. Its association with albinism and deafness leads to its exclusion in more than one breed however.

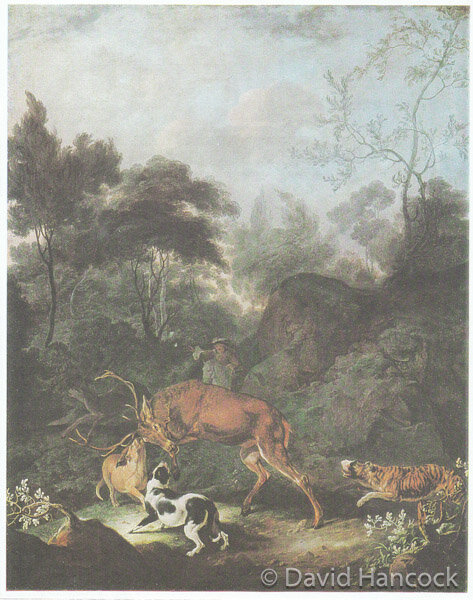

It is no surprise to find this breed type portrayed in Italian medieval paintings or engravings in both hunting and pastoral scenes. If you look at Italian paintings of the period 1400 - 1600AD, you can soon identify big, strapping, strong-headed, alaunt-type dogs in some of them. From the studios of 15th century painters such as Ghirlandaio, di Giovanni, del Sellaio, Pisanello and Mantegna came remarkably similar portrayals of these mastiff type dogs. Later came Tempesta (1555-1630), painter and engraver, most of whose sporting scenes were inspired by his tutor Stradanus. Later Philipp Hackert (1737-1807), in his Fernando IV of Naples Hunting Boar at Cassano and his Dead Boar and Mastiff of 1795, depicted this same type of powerful hunting mastiff, as did Cingarolli in 1780. The Cane Corso is easily linked with the Italian portrayals; it is important to note that the work of artists like Pisanello was characterised by a minute and accurate observation of reality, without excessive romanticising. Their work therefore has importance for cynologists.

The mastiffs of Italy have attracted comments from various writers, as these quotes show:

"The people of Colophon and Castabala kept troops of dogs for war purposes, and these used to fight in the first rank and never retreat; they were the most faithful auxiliaries, and yet demanded no payment."

'Historia Naturalis' by Pliny, (23-79AD)

"The horsemen of Magnesia in the Ephesian war were accompanied to the battlefield each with a war-hound, the dogs in a body attacking the enemy, being backed now by the foot soldiers, now by the cavalry, and thus rendering great assistance."

"Gleanings from the Natural History of the Ancients" by the Rev. W Houghton, 1879

"Paulus Jovius writeth touching Amidas the King of Tunis, that he was wont not only to cause dead bodies to be cast to the dogs to feed them, but also to let loose hungrie dogges upon live bodies. to tear them the more furiously...it was reported, That Francis Carrera, prince of Padua, kept great Mastives by which he caused his subjects to be strangled and devowred."

'Living Librarie (History of Venice)' by P. Camerarius, 1625

It could be that the breed known as the Neapolitan Mastiff is the nearest and truest inheritors of the mantle of the famed 'Indian' dogs, or mastiff dogs of the Hyrcani, as they were known to the Ancient Greeks. These latter dogs descend from the huge mastiffs employed in the hunt by the Assyrians and are depicted on their well-known artefacts. Such a theory would cause fanciers of the Mastiff breed of England in the Victorian Age, like MB Wynn, author of 'The History of the Mastiff' of 1886, to turn in their graves. For they saw the Mastiff breed of England as the fount of everything mastiff. It would please the Italian promoters of the Neapolitan Mastiff and the Cane Corso, the two Italian mastiff breeds. But such promoters so often spoil their case by blurring their breeds with the Molossian dogs, which researchers so regularly confuse with the mastiff breeds, despite the evidence to the contrary. I suspect too that the Neapolitan Mastiff was once an even bigger breed. An abundance of loose skin, a distinct breed feature, is a sign to me of a breed 'bred down' in size, rather like the Basset Hound. Breeders can alter the leg length and overall anatomical size but they are unable to reduce the surface area of skin. In this connection, it could be that the Chinese Shar Pei is a much reduced modern specimen of an ancient Chinese mastiff breed. The wrinkled coat being the main clue. Of course the sad tendency of breeders to exaggerate unusual features in a breed is a factor in excessive skin in any breed, but some excess was there to a lesser degree in the first place.

There are strange theories linking the looseness of skin on dogs with an enhanced capability to turn when gripped in the dog-fighting ring or still be able to bite back when seized by an opponent, but they lack credibility. Pit Bull Terrier breeders would have pursued such a feature ruthlessly if it had any validity. The holding or gripping dogs were expected to have tough thick skin to withstand tusks and horns the better. The thinner coat of the running mastiffs, like the boarhounds, was rightly considered to be a serious liability. I remain to be convinced too of the sense of the Neapolitan Mastiff (and Fila Brasileiro and the Alano) being preferred by some fanciers to be higher at the croup than at the withers. This detracts from the symmetry of their appearance and affects their gait, since their hindlegs are unnaturally longer when the croup is higher than the shoulders. There is no sign of this feature in the bas-reliefs of the Assyrian hunting mastiffs, from which some misguided Neapolitan Mastiff fanciers claim their breed is descended. It does not manifest itself acceptably in the sister mastiff breeds and is undesired in just about every other breed.

The Neapolitan Mastiff (although some claim this was the Cane Corso type) has been called the 'cane de presa', or gripping dog, in Naples, just as the Spanish sister breeds are called Perro de Presa Canario and Perro de Presa Mallorquin and the Portuguese and Brazilian related breeds Fila de Sao Miguel and Fila Brasileiro respectively. Presa or Fila means seizing and holding and refers to the same characteristic as found in the 'beissers' further north. The dogs used to hold or grip there were called barenbeissers, for use on bears, bullenbeissers, for use on bulls and bufalbeissers when used on buffalo or bison. This group of dogs was immensely valuable to man in the hunting field before the development of firearms. Cattlemen still use them in the Azores and South America, with North American ranchers also trying them.

It is vital, now that the Cane Corso and the Neapolitan Mastiff have been recognised as distinct breeds, for each of them to retain their own special breed points. There is a theory that once breeders preferred the heavier and much more wrinkled variety now known as the Neapolitan, then the lighter tighter skinned dogs were given to farmers in the neighbourhood as stock dogs. This latter type was utilised by butchers. In Sicily, a type called the Branchiero Siciliano was favoured and developed a slightly different phenotype, just as the flock protector the Cane di Manerra developed as a variation of the Abruzzi sheepdog. The Abruzzi sheepdog, a bigger fiercer version of the Maremma sheepdog, has been crossed with the Cane Corso to produce the 'Mezzocorso', a more abrasive flock protection dog. Similarly, the 'Mezzosangue' is a mix of Cane Corso and scent hound to improve tracking qualities and the 'Mezzolevriero' a blend of Cane Corso and sighthound to improve speed. (The 'boar-lurcher' of central Europe and the alaunt veltreres referred to by De Foix each consisted of this mix.) The 'Vuccerisco' of Sicily was of this type and is being restored, as is a Cane Corso variety in Calabria called the 'Bucciriscu'. Sardinia possesses another variety called the Dogo Sardo, a cattle dog, usually brindle and not seen outside that island. The fanciers of the Cane Corso claim that it is their breed that is 'the true hunting mastiff' of Italy.

The Cane Corso has a short dense coat in a range of colours: black, mahogany, chestnut, fawn, blue or these colours brindled. Its tail is docked to one-third of its length. Strongly boned and well muscled, the breed looks more mobile than its Italian sister breed, the Neapolitan Mastiff. Even with a minimum height of 24" and a minimum weight of 100lbs, the Cane Corso is smaller than the Neapolitan but sensibly, whilst size is valued, it is firmly stated not to be at the expense of activity or movement. I understand that in southern Italian dialect, mainly the Puglia region, 'Corso' still means strong in the sense of robust. The breed is mentioned by Teofilo Folengo in his 'Macheronee' of the twelth century and Erasmo de Valvasone in his poem of 1591, called 'The Hunt': "The Cane Corso is very powerful, he attacks the wild cat fiercely, and once he takes hold does not let go." Remarkably similar dogs were used for bull-baiting in Italy in the 18th century.It is worth noting that the Alans, famous for their huge hunting mastiffs, were valued in Roman times for their small, swift horses. In a well-known inscription found at Apta on the Durance, the Emperor Hadrian praises and commemorates his 'Borysthenes Alanus Caesareus Veredus' that 'flew' with him over swamps and hills in Tuscany as he hunted the wild boar. The Romans hunted the wild boar with hunting mastiffs; the Alans could have provided hounds as well as horses, their renowned Alauntes. The governors of Milan were once commended "because they mixed horses as breeders with large mares, and there have have sprung up in our region noble Destriers (the war horses of medieval knights, DH) which are held in high estimation. Also they reared Alanian dogs of high stature and wonderful courage."

The Cane Corso was identified as a separate breed by cynologists such as Dr Paolo Breber and Professor Giovanni Bonatti in the early 1970s and thirty specimens were chosen to start a controlled breeding programme. Devotees like the Leone, Caldarola, Cilla and Principe families had loyally retained their own bloodlines for generations. Enthusiasts like Casalino, Gandolfi, Serini and Malavasi, whose kennel was selected to pioneer the breeding scheme, were mainly responsible for the breed's restoration. The breed outnumbered the Neapolitans at the Italian native breeds show of 1994. For those who favour the mastiff phenotype but dislike the wrinkle and loose lips of the Neapolitan, then the Cane Corso is likely to be preferred. But the former attracts staunch supporters who find the character of their dogs so rewarding. The Cane Corso is experiencing a steep rise in popularity outside Italy. The American imports are gaining strength there, although they tend to be represented by the more Neapolitan Mastiff type which many Italian breeders would claim lack genuine breed type. Far from being a lost 'ancient' breed, the Cane Corso is thriving!