Number

Title

By David Hancock

RESPECTING FORM AND FUNCTION

The value of shepherds to the human race over many centuries is indisputable; the value of their dogs to the shepherds has long been accepted as immense and unmatchable. In remote areas where sheep are grazed the worth of such dogs is still immeasurable. In western urbanised countries, the types of dogs that once were known only to shepherds have been developed as distinct breeds and have earned widespread popularity away from the pastures both as companion and service dogs. The competitive exhibiting of such has predictably changed their appearance, as cosmetic appeal inevitably outscored working skills no longer exercised. The challenge today is to protect such admirable dogs from human excess, think much more of their best interests and respect their heritage. Shepherds have used dogs for perhaps two thousand years. Man has conducted dog shows for less than two hundred. We would be very foolish to ignore the hard lessons learned by shepherds over many centuries and think we know better. The dogs of the shepherds deserve to be perpetuated in their own mould, not to a transient template produced by the all too often self-indulgent breeders of today. These are precious and important breeds of dog.

There is a strong case for the origin and function of all pastoral types, ancient and modern, to be respected, not in the pursuit of historical accuracy, important as that is, but because they can only be bred both soundly and honestly if their past development and traditional form is honoured. Their original lowly rural breeders have left these magnificent canine servants to us and we have a duty of care towards these impressive and quite admirable breeds of dog. There is less research material on the dogs of the shepherds than say on sporting dogs such as gundogs and hounds. Both the latter types were owned and patronised by the wealthy and better-educated, the former usually by illiterate agricultural workers. This increases my resolve to do them justice after centuries of neglect. My personal affection for this type of dog rests on the thirty-odd years of loyal yet stimulating companionship that I was given by my own working sheepdogs, perhaps better described as unregistered Border Collies; they taught me an enormous amount about dogs – and quite a lot about myself.

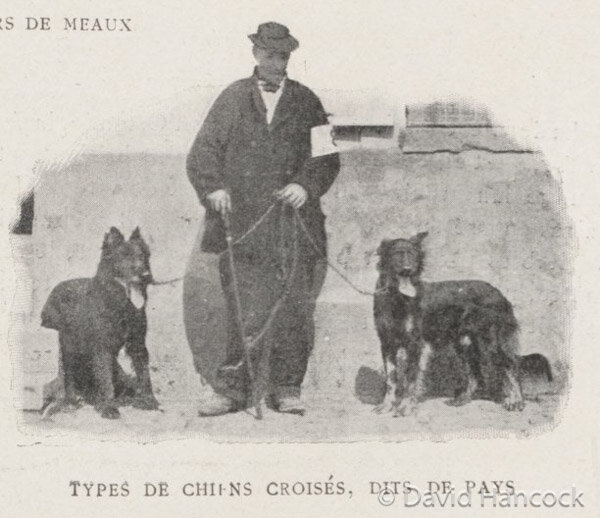

Pastoral dogs bred for work have long lacked breed recognition; they were and still are in the pastures identified by the type that best functions. Many since recognition by kennel clubs the world over have become just additional show breeds, not bred for work. Never listed by the KC were the Smithfield Sheepdog (a leggy, shaggy-coated drover’s dog), the Blue Shag of Dorset (a mainly blue-grey bob-tailed sheepdog), the Cotswold Beardie (often black and white and possibly a variant of the Bobtail), the rough-haired Lakeland Sheepdog, the Welsh Hillman (the longer-legged uplands sheepdog of Wales), the Old Welsh Grey (the bearded sheepdog of Wales), the Welsh Black and Tan Sheepdog (the shorter-coated ‘valleys’ sheepdog of South Wales), the Galway Sheepdog of Southern Ireland (a big tricolour dog – resembling the Bernese Mountain Dog) and the Glenwherry Collie of Antrim (a mainly merle or marbled type, often wall-eyed), each one a distinct type, however little known outside their favoured areas. Every year, the use of pastoral dogs declines a little further, as modern pressures alter our agricultural methods and the urban sprawl continues. But every year it seems a new use is found for that talented breed - the Border Collie, as its sheer versatility and wide range of skills find employment. It is now the case that many pastoral breeds are, more often than not, unlikely to be utilised in the pastures and far more likely to be employed as service dogs, with the military, the police and search and rescue organisations. They are still valued; they can still do things that humans cannot.

How should a working breed, brought in from the pastures, be exhibited and then judged? Should not the paramount desiderata be: soundness of anatomy, powerful movement, hard muscular development and alertness in the eyes. Or, bearing in mind that show dogs are unlikely to do a day’s work, should judges be seeking out show points: the ‘very abundant mane and frill’ in the Rough Collie, the ‘clean wedge of skull’ in the Smooth Collie, the ‘bear-like roll’ in the Old English Sheepdog, the ‘foxy head’ in the Corgis and the ‘great size’ demanded of the Pyrenean Mountain Dog? These features may make the breed but do they make the dog? Who keeps a breed honest? The KC? The Breed Council? Or the judges, when awarding rosettes? The 'rosetted' dogs get bred from; that surely influences the breed more than any collection of words. Judges’s decisions can have far-reaching consequences: in exhibitor expectation, in future breeding choices and in breed morphology.

Tapio Eerola, the PR officer of the World Dog Show, held in Helsinki, and editor-in-chief of the Finnish Kennel Club magazine produced these enlightened words in the commemorative issue for that show: "Dog breeders should pay careful attention to which direction they want their breed to go. If the exaggeration of specific features continues in winning dogs the heavy bone structure will get heavier and heavier, short body becomes even shorter, deep chest deeper, wide head wider and long hair longer...Although the World Dog Show is essentially a beauty competition, nothing prevents us from taking up the theme of healthy dog breeding here also." This was highly responsible campaigning by perhaps the most impressive kennel club in the world. There should not and need not be a difference between enthusiastic dog show exhibitors and morally-motivated dog owners; the pursuit of certificates need not preclude the pursuit of healthier-bred, sounder dogs. Nothing but we ourselves prevents us from taking up

the theme of healthy dog breeding here as well.

But if you read the judges’s reports on the pastoral breeds in recent years, you can soon see that all is far from well. Take the words on just one pastoral breed’s showing, the Shetland Sheepdog classes, in just one year, 2011: “I struggled to find any with the correct angle of upper arm and shoulder…the worry is that no one seems to be taking any notice and now the lack of angulation is becoming the norm. I found just seven dogs in the entry with anything like the correct conformation.” “Construction still needs to be addressed, particularly steepness and shortness of upper arms…” “…as always shoulder angulation still gives concern, being in some cases short and steep.” And, alarmingly: “I would just like to say that the breeders/exhibitors seem to be concentrating more on head, expression and fullness of coat to the detriment of construction.” “There is more to a Sheltie than a big coat and a pretty face, but there does seem to be a move towards this which is a great worry.”

It is a sad fact that most dog breeders breed on the phenotype, i.e. what the parents look like, rather than the genotype, i.e. what genes are able to be passed on. Breeding living creatures can only ever be an exercise in genetics and breeders seeking to establish a line of consistent type must accept that every dog and bitch mating is a blending of two families not just of a sire and a dam. The phrase that seems to lead to mistaken assumptions is the one that states that a puppy gets 50% of its genes from the sire and 50% from the dam. A better, more accurate, more valuable phrase is that a puppy gets 50% of its genes through its sire and 50% of its genes through its dam. That is why it is simply vital to know what stock is behind the parents of the puppy.

Breeding pedigree dogs is made more risky in Britain by the lack of reliable records. It is automatically assumed that the written pedigree is accurate whereas an alarming proportion of them are not. No dog has to be individually and irrevocably made identifiable by way of a tattoo or microchip. Judges in the show ring and owners of bitches only have someone's word that the dog before them in the ring or the sire being used for the service is the one named on the pedigree or put forward as such. It only needs one prolific breeder to be dishonest for the whole breeding record of a pedigree breed to be made unreliable. The written pedigree too is restricted to number, gender, colour and breed; there is no record of the strengths or faults of the dog on its pedigree despite show critiques containing detailed comment being available after every major show.

A 2013 study at the University of California Veterinary Teaching Hospital used medical records from 27,000 dogs over 15 years to study 24 known genetic disorders in dogs such as cancer, dysplasia, cardiac problems, patellar luxation and epilepsy. Analysis indicated that ‘genetic disorders were individual in their expression throughout the dog population’ and that ‘some genetic disorders were present with equal prevalence among all dogs in the study, regardless of purebred or mixed-breed status’. The show world immediately took this to prove that purebred dogs were no less healthy than crossbred ones; but which breeds contributed to the mix? This study actually found that ten of the disorders under scrutiny were more prominent in purebred dogs. These were aortic stenosis, dilated cardiomyopathy, hypothyroidism, elbow dysplasia, intervertebral disc disease, atopy, dermatitis, bloat, cataracts, epilepsy and shunt. Fourth highest in intervertebral disc disease was the Pembroke Welsh Corgi; first in the elbow dysplasia category came the Bernese Mountain Dog, with the Anatolian Shepherd Dog in fifth

highest. Mixed breeds showed the highest percentages affected by cruciate ligament ruptures, perhaps from the unwise crossing of two breeds with very different skeletal structures. The lesson from such a study is that breeding stock must be screened for those disorders where screening is possible.

If you consult authoritative books like Gough and Thomas’s Breed Predispositions to Disease in Dogs and Cats (Blackwell, 2004) and Clark and Stainer’s Genetic Aspects of Pure-bred Dogs (Forum Publications, 1994), you can soon discern the worrying threat to the well-being of our pastoral and working breeds from faulty genes. In the Australian breeds, the cattle dog has recognized ophthalmic problems such as cataracts, lens luxations and progressive retinal atrophy, with congenital portosystemic encephalopathy most common in this breed. Hereditary cerebellar abiotrophy has been diagnosed in Kelpies. A number of different eye problems have been reported in Australian Shepherds, together with hereditary deafness associated with the merle, piebald or extreme piebald genes. Rough Collies can suffer from dentition problems arising from too narrow a bottom jaw, micropthalmia from having small eyes and many veterinary dermatologists find the breed very susceptible to demodicosis, hydradivitis and nasal pyoderma, linking this with the heavy coat. The Bearded Collie has a low incidence of hereditary and congenital defects, although certain bloodlines produce dogs with a form of epilepsy. Breeders of Malinois have reported a high incidence of neoplasia; hypothroid is of concern in the Tervueren and epilepsy has been reported but the breed is relatively free of hip dysplasia. The Shetland Sheepdog has the longest list of hereditary defects, with the breed having its own form of disproportionate dwarfism, often found when the parents themselves are unaffected. This list, across these breeds, sounds daunting but the pastoral and working breeds suffer the least from such flawed genes.

One of the difficulties facing breeders of live animals, whether it’s dogs or parakeets, is that professional scientists have made genetics a foreign language. The role of the expert surely is to make a complex subject more easily understood. Scientists are not good at this and yet display impatience when their work is misunderstood or not heeded. Dog breeders know too that there has never been a geneticist among the most successful of them. Geneticists are scientific advisors and breeding is an art as well as a science. They can advise us on how diseases that are inheritable are passed on. They can advise us on how physical and mental characteristics are likely to be passed on. But in the end the skill of the breeder lies in selection, the selection of breeding stock, the selection of parents and the selection of a breeding path to follow.

Selection based on the mere fact that the dam is a nice pet and ought to be bred from, or has won a couple of prizes and her pups will bring in income, or the future chosen sire is a current big winner, contributes little to a breed and even less to the reputation of the breeder concerned. No bitch should be bred from just because she is female and fertile. Puppies should, in the genuine dog-lover's world, never be produced to suit someone's bank balance; there are already too many unwanted and ill-kept dogs in Britain. For any breeder to mate his precious bitch to a dog just because the dog is currently winning well is sheer folly. It assumes that the judges rewarding the sire are knowledgeable and unbiased - but are they? And even if the sire to be is a worthy champion, what family does he come from? The genes of his ancestors will come through him.

Until we have better data from approved national schemes, selection of breeding stock will rely on the researching skills of each individual breeder. With the accuracy of the written pedigree never being checked by the Kennel Club, just the breeder's word accepted, with no mandatory health clearances, no national dog identification scheme and no information of breeding value on the written pedigree, coupled with untrained judges rewarding unworthy dogs, any breeder faces an uphill battle in the pursuit of breeding better dogs. The appointment of a geneticist for each breed and the appointment of a breed archivist to verify pedigrees, together with a grading system to establish just how good each dog is, would help enormously. Sire ranking lists are available to livestock breeders but not yet to dog breeders - how long can that continue? It is just not good enough to rate a sire by how many champions he has sired; who is testing his offspring for genetic quality?

Novice breeders may well despair of finding the essential data on which to base their breeding programme. Veteran breeders usually know that dogs bearing this particular affix display certain good qualities, whilst those bearing another one feature other complementary ones. Shrewd breeders usually utilize an older stud dog, his track record can at least be examined. There is financial sense in a small breeder not kenneling his own stud dog but using outside blood to a well-researched plan. Long established kennels in every breed often develop their own kennel signature or kennel type. When this conforms precisely to the breed standard, it provides valuable stable genetic material. But when one influential breeder is producing untypical stock, however attractive or successful, it is most important for the novice breeder to detect this. In the end, the breed standard is the breeding blueprint, a design for the future product. Knowledge of it and more important still, an understanding of it, is essential for the successful breeding to type in a pure-bred breed of dog.

Whatever their role, their work, the climate and the terrain demanded excellent feet, tough frames, weatherproof coats, enormous stamina, really good eyesight and hearing and quite remarkable robustness. These dogs operated in harsh conditions, ranging from the hottest to the coldest, the stoniest, thorniest, windiest, most mountainous and most arid areas of Europe and Western Asia. Farmers and shepherds had to have entirely functional dogs; physical exaggeration does not occur in any of the flock-guarding breeds, unlike the ornamental ones. Hunting ability was not desired although the physical power and bravery of such dogs did lead to their use in bear hunts in Russia and boar hunts in Central Europe, where they were used at the kill, not in the hunt itself. The demands of climate have led to both the flock guardians and the shepherd dogs featuring appropriate coats for their region. The Hungarian Komondor and the Italian Bergamasco display the thick corded or felted coats required to survive in their working environment. The Swiss Entlebucher and Appenzeller and the New Zealand Huntaway exhibit the smooth sleek coats best suited to their working conditions.

If we then look at the shorter legs of the heeling breeds, like the Corgis, and the longer legs of the herding dogs, like the Belgian, Dutch and German Shepherd Dogs, we can see how not only climate but also terrain and function determined type. In some areas the harsh-haired or goat-haired breeds, like the Bearded Collie and the Schapendoes of Holland, were favoured, because of the local conditions and their instinctive skills. The breeds were shaped by the farmers’ needs. Wherever they worked or farmed, farmers needed dogs with the innate characteristics, the appropriate physique and the suitable length and texture of coat to protect, drive or herd their stock, hunt down vermin and guard their farmsteads and pastures. Their demanding requirements have left us with some of the most popular breeds of companion dog today, although, sadly, these are so often bred more with cosmetic than functional considerations in today’s society.