1152

QUICK TO CATCH

By David Hancock

Any dog can chase cats, pursue deer or ambush a grey squirrel. But, for good or ill, a sighthound stands a better chance of succeeding than most. Being built for extreme speed, having exceptional eyesight, acute hearing and a good nose for air-scent, is all very well but, if the hunting instinct is not there too, you do not have a hound at all. In his book The Mind of the Dog RH Smythe, vet, exhibitor and sportsman, writes “ Much of the work carried out by dogs, whether it be chasing the live or dummy hare, hunting and tracking and so on, is really natural behaviour adapted to certain ends…One can only marvel at the instinct which compels a pack of greyhounds to chase a mechanical hare several times a week with no hope of ever catching it.” When dog’s natural behaviour is harnessed by man, it is reinforced by dog’s equally natural desire to please its human owner; training a member of the speedster breeds, however, is not a recommended task for a new dog owner. Dog breeds are often selected by their future owners because of their appearance; this leads to mis-matches. Owners must always be aware of the reason their potential purchase came into being – what they were for. As Stanley Coren points out in his The Intelligence of Dogs of 1994: “Sighthounds, for example, will chase things that move. This means that attempting to work or train your greyhound, whippet, saluki, or Afghan hound in a busy area, such as a park where children and other dogs will be running around, will simply make the task more difficult. If you must train outdoors, use a relatively empty field or yard…you can take advantage of these breeds’ responsiveness to visual stimuli by using large and exaggerated hand signals during training rather than simply depending upon voice commands.” But the pursuit has to be for a purpose – to catch the quarry. Glamour and physical appeal is superfluous if performance is sacrificed.

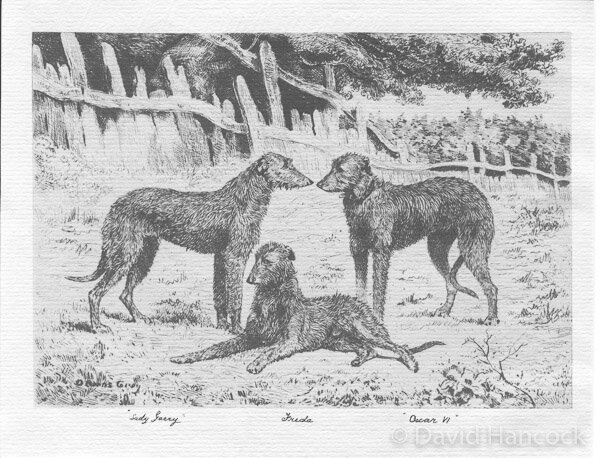

Many of the sighthound breeds are: glamorous, like the Afghan Hound, physically beautiful, like the Saluki, aristocratic, like the Borzoi, and seemingly gentle-natured, like the Deerhound. But they were designed and then bred to hunt and kill, whatever their gentleness away from the hunting field. They are favoured by some because of their sheer handsomeness and I have no criticism of that. But I am concerned that such attractive breeds can end up being valued only for their looks and their spiritual needs overlooked. Their instinct to chase and catch other animals too needs to be acknowledged. There are dangers in overlooking the basic fact that sighthounds were selectively bred and specifically intended to kill other mammals. Instincts, however deeply buried, are still there. They need to be exercised but in a controlled way.

Some years ago, I lived near a well-meaning lady who rehomed two racing Greyhounds. They were delightful dogs and I support her kindness and compassion. She looked puzzled when I warned her that they needed retraining if exercised off the lead, because the only world they knew was chasing small furry moving objects. Her two new pets appeared so gentle, so unaggressive and so shy that she relaxed, a bit too much. A tradesman left a side-gate open one day and her retiring retired Greyhounds got out - and killed two cats and savaged a Dachshund within half an hour. The poor lady was devastated; but whatever their disposition, these two dogs were only doing what their inbred instincts told them they should be doing.

Some years before that, I used to walk to work in London through St James's Park and often passed a lady walking her beautifully groomed Borzoi. The hound was very well trained, never pulled on the lead and seemed to ignore the many wildfowl that crossed its path. Then one day a grey squirrel dared to dash across the ground moving from one huge tree to another. The Borzoi shot forward so strongly and unexpectedly that the lady lost the lead and the grey squirrel had a nasty surprise but met a quick end. The lady was distraught, saying that the dog had never even seen a grey squirrel before. Her chosen breed was however a hunter, one bred for centuries to catch and kill. For all their elegance and reticence all sighthounds were designed to hunt and kill.

More recently, a Whippet owner wrote in one of the dog papers that she had had a distressing incident in the New Forest with her dog. She had taken her dog into an official car park and let her dog out of the car for its usual walk, as she had many times before. On this occasion the dog suddenly dashed into nearby undergrowth and disappeared. The lady went after her dog only to see it seize a small deer by the hamstring after the briefest of chases. She was able to call the dog off but had to call a ranger to deal with the crippled creature, which was later destroyed. The lady was aghast at what her Whippet had done, understandably so in those circumstances. This dog had never hunted before, but it had gone straight for the deer's hock. Of course, any dog can chase cats, pursue deer or ambush a grey squirrel. But a sighthound stands a better chance of succeeding than most. It isn't just sheer speed, agility comes into it as well – and the desire to catch.

We have to be extraordinarily careful that in the pursuit of show success, whether in lurcher rings or at KC-licensed events, we do not end up destroying the key elements in these beautiful functional breeds. A sighthound needs lung and heart room in abundance; it must have great forward extension, facilitated by sound shoulders. Short straight upper arms are creeping into so many sporting breeds these days and it is introducing quite untypical and most undesirable movement. The importance of sound shoulders can never be stressed enough in any hound breed. A hound built for speed, whether a Spanish Galgo, a Hungarian Agar, a Tasy or a Taigon from Mid-Asia, a Moroccan Sloughi or an Azawakh from Mali, must have the anatomical attributes which provide sprinting power. Some foreign sighthound breeds look different now from the original imports; the Afghan Hound certainly has more coat and the Borzoi can feature a markedly convex back as opposed to the more or less level topline of the early hounds.

In "The Hunter's Calendar and Reference Book" published in Moscow in 1892, the Borzoi is divided into four groups: Old Russian or Psovoy/Gustopsovoy Borzoi, with the longer coat, Asiatic, with pendant ears, Hortoy, smooth-coated, and Brudastoy, stiff or wire-haired. At the Crystal Palace Show in the 1890s a man called Zambaco exhibited a Circassian Orloff Wolfhound called Domovoy, 32½" at the shoulder and wolf-coloured. It was described as being longer-legged than the Siberian hound, with a flat, close-lying coat rather than a wavy one. At the Botanic Gardens Show of 1903, a Circassian Harehound, 20½" at the shoulder and silky-haired, was exhibited. She had particularly large feet and was said to turn tighter than a Greyhound.

Circassia, now part of the Karachayevo-Cherkess region of Russia, was once under Turkish rule, being north of the Caucasus near the Black Sea. Not surprisingly, many regions featured their own sighthound variety, the hounds' capability as pot-fillers being valued. The Polish Greyhound, Chart Polski, from further north is exhibited at the World Shows but the Albanian Wolfhound, from the Balkans, has not emerged as a distinct breed. All these hounds, wherever they come from, display the classic sighthound phenotype: tucked-up belly, long narrow head, long straight muscular legs, arched loin, ribs carried well back, long neck, sloping shoulders, level topline, croup falling away to allow great forward extension from the powerful hindlegs, mobile ears and a long tail. The aim with every sighthound breed is to produce a hound fast enough to chase and determined enough to catch. The anatomy needs to be backed by fierce desire.

This sighthound mould developed from function and a show judge who doesn't punish upright shoulders and short upper arms is doing the sighthound breeds a considerable disservice. Movement of course reveals such faults, a well-constructed sighthound should 'daisy-clip' with spring in its step and a minimal uplift of feet. This effortlessness when moving is a prized sighthound asset and directly related to correct construction. The Afghan Hound has a higher front foot action, perhaps from a greater length of upper arm and claimed to originate from having to negotiate rocky terrain in its native country. Yet there is no appreciable difference in movement or hunting desire between the desert or plains type and that from the foothills.

It is so pleasing to know that Afghan Hound (and Saluki) racing is conducted in Britain; what a release for the hounds! Less pleasing is the knowledge that the best Afghan Hound racer, Fox Ellis, which won the national individual championship a record five successive times, was never used at stud. A litter sister became a champion but for Fox Ellis not to be used at stud tells you more about breeders seeking show-winner blood ahead of proven construction than I ever could. The sighthound breeds only survived to enter the show arenas because of their ability to race. In this connection it was sad when in refusing registration to fine Syrian Salukis one enthusiast wished to import the Kennel Club gave the comment: "It would be difficult to believe that breeding patterns within desert tribes would be as strictly controlled as those under the aegis of the Kennel Club."

This needlessly pompous statement reflects badly on the KC, whose "strictly controlled breeding patterns" are based solely on breeder honesty. Arabian breeding patterns are decided entirely by performance. Whose sighthounds would you prefer? An infusion of genes from sighthounds judged wholly on performance would have done the breed of Saluki in Britain so much good. Closed gene pools so often indicate closed minds too. Elegance in the ring does not produce hunting dogs! Buried or suppressed instincts are still genetically important.

Some historians believe that the sighthounds in Eastern Arabia came from Asia originally. Studies on the blood of the Azawakh and the Sloughi showed that both have an additional allele on the glucose-phosphate-isomerase gene locus not found in other sighthounds and dogs but present in the coyote, fox and jackal. These two African breeds showed the greatest genetic distance from the other dogs in this study. This suggests a different historical development. Wherever any sighthound breed comes from and whatever its coat length, we should respect their heritage, perpetuate them as honourably as Bedouins do and "control" their breeding just as strictly as the latter do. Is any sighthound not physically constructed for hunting and motivated by catching really a sighthound at all?

"This Dog hath so himself subdued,

That hunger cannot make him rude:

And his behaviour doth confess

True Courage dwells with Gentleness."

Those words of Katherine Philips, in her poem "The Irish Greyhound", convey at once the nature of the sighthound breeds. Many of these breeds are glamorous, like the Afghan Hound, physically beautiful, like the Saluki, aristocratic, like the Borzoi, and seemingly gentle-natured, like the Deerhound. But they were designed and then bred to hunt and kill, whatever their gentleness away from the hunting field. They are favoured by some because of their sheer handsomeness and I have no criticism of that. But I am concerned that such attractive breeds can end up being valued only for their looks and their spiritual needs overlooked. Their instinct to chase and catch other animals too needs to be acknowledged. Tribes from the Bedouin to the Celts valued them, as John Whitaker wrote in the late eighteenth century:

“Let the brisk greyhound of the Celtic name

Bound o’er the glebe and show his painted frame.

Swift as the wing that sails adown the wind,

Swift as the wish that darts along the mind,

The Celtic greyhound sweeps the level lea,

Eyes as he strains and stops the flying prey,

But should the game elude his watchful eyes

No nose sagacious tells him where it lies.”

Urbanisation will gradually erode our fancying the sight-led speedsters of the canine world. But in the meantime, let’s continue our admiration for their astonishing athleticism, remarkable hunting skills, huge desire to catch their prey and sheer stylishness, right across the world. The story of the ‘canine cursorials’ – dogs having limbs adapted for running, that find their prey in open country and hunt it using great pace, often over considerable distances, will as they say, run and run! They rely on speed, yes, but their whole purpose is not to run but to catch. But they do need long views in their hunting field. It is no surprise therefore to find their most effective use in deserts, on steppes and prairies or level rocky terrain, from Syria and Iraq to Afghanistan and Russia. They were valued by hunters from ancient Egypt and classical Greece, then in turn, by tsars, sheikhs and western noblemen. Arrian, the Greek historian, wrote in 124AD: “I myself have bred a hound whose eyes are the greyest of grey. A swift, hard-working, courageous, sound-footed dog, and she proves a match at any time for four hares. She is, moreover, most gentle and kindly-affectioned…” That is a timeless description of the sighthound function and nature. The quick to catch hounds might even, when the force of nature changes in parts of the world for some unpredictable reason, be revalued and re-employed – in any reversion to primitive living, man badly needs them! Pretty dogs without hunting instincts are not hounds at all!