1175

DOGS FOR BIG GAME HUNTING

By David Hancock

I have never been on a big game hunt and have no desire to do so, but it is fair to look back at both the hunters and their dogs to study the methods used on the various quarry and the type of dog used. In these conservation-minded days, tales of derring-do in hunting big game, whether in Africa or Asia, Central Europe or South America, are no longer considered worthy of admiration. And, whilst I welcome our more compassionate, contemporary approach towards such hunting, we must be careful not to condemn such past activities by viewing them solely through 21st century eyes. Big game hunters were once regarded as heroes by their contemporaries. They usually endured great hardship, were vulnerable to a wide range of often life-threatening diseases and were equipped with less reliable firearms and ammunition than today. Most ‘shooting’ of big game nowadays is more safely conducted through the camera than the carbine. The invention of firearms brought not just enormous bonusses to hunter-sportsmen but a greatly reduced risk to their lives. This reduced their dependence in some forms of hunting on determined, courageous dogs. We live in times when powerful dogs brave enough to tackle boar, bear and bison are banned in some countries, not because of any current misdeeds, but purely because of their past as a type of dog. In modern times too, a dog that can singlehandedly catch a hare is valued less than a dog that can only retrieve a dead rabbit.

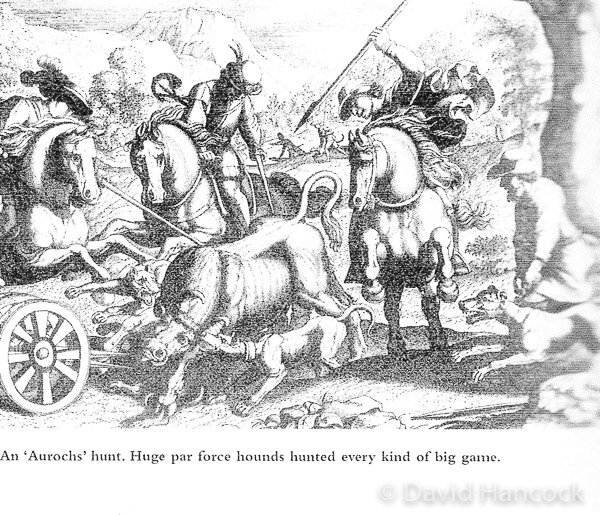

It would be good to see appropriate recognition for the hunting mastiffs, whether described as seizers, holding dogs, pinning dogs, gripping dogs, perro de presas, filas, bullenbeissers or hetzruhen. They should at least be respected for their past bravery and bred to the design of their ancestors. A former big game hunting breed like the Mastiff of England, once famed as the Englische Dogge, is prized nowadays solely on its bulk. It is possible that in the boar-hunting field in Central Europe in the period 1500 to 1800 more catch-dogs were killed than the boars being hunted. In those days there was a saying in what is now Germany that if you wanted boars' heads you had to sacrifice dogs' heads. In his 'Hunting Big Game in Africa with Dogs' of 1924, the American Er M Shelley describes how the catch-dogs were not allowed to run with the trailing hounds but held by natives until they were needed. This was the role of the hunting mastiffs in medieval Europe. This is why I believe the term 'bandogs' referred to leashed catch-dogs and not to chained yard dogs as many writers record. The risks to the dogs in hunting big game are described by Shelley: "Dogs are very fond of hunting them (i.e. warthogs), but it usually proves disastrous for the dog, for these hogs have two long tusks that protrude far out from the lower jaw, and they use them with deadly effect. Dogs can be maimed or killed much more readily by hunting these hogs than by hunting lions." Great artists such as Rubens, Snyders, de Vos, Hondius and Tempesta depicted big game hunts, with even lion, hippo and auroch as the quarry.

Ostrich hunting by mounted huntsmen and catch-dogs was a favoured medieval sport in parts of Africa, the huntsmen using lances or spears with long shafts to attack the prey. Catch-dogs are used to this day in Australia in the kangaroo hunt. The renowned Australian 'roo culler, Charles Venables, hunted kangaroo for over fifty years, using Deerhounds, Deerhound lurchers or staghounds, Foxhounds and Jack Russell-type terriers. He favoured Bullmastiff bitches as catch-dogs. In the 16th century aurochs and wild bulls were hunted by mounted hunters, again using lances and catch-dogs. Water buffalo have proved more difficult to hunt with dogs, mainly because of their preferred habitat and style of living. Big game hunting became almost an obsession with some Victorian sportsmen, one even trying to popularise his chosen 'sport' of "stag-riding", in which he leapt from his horse's back on to that of the startled animal. He was alleged to have been 'greatly disappointed' when this more than exciting sport failed to catch on! The less zany Sir Samuel Baker describes in his book 'The Rifle and the Hound in Ceylon' the use of various dogs in big game hunting. He took a pack of thoroughbred Foxhounds there with him from England, but only one survived a few months hunting in Ceylon. He favoured, for elk-hunting, a cross between the Foxhound and the Bloodhound, rather like the old English Staghound, using fifteen couple, supported by lurchers.

Baker stated that the great enemy of any pack was the leopard, which would leap down on stray or isolated hounds and kill them. Baker was fond of 'deer-coursing', the pursuit of axis or spotted deer using Greyhound and horse. He used pure Greyhounds, "of great size, wonderful speed and great courage." A buck could weigh 250lbs and would turn and charge its pursuers, unlike the elk which stood at bay. With some sadness he wrote that "the end of nearly every good seizer is being killed by a boar. The better the dog the more likely he is to be killed, as he will be the first to lead the attack, and in thick jungle he has no chance of escaping from a wound."

The sheer scale of big game hunting, whether by Genghis Khan when training his cavalry or by Central European hunts more recently is hard to visualise in our times. On the 12th of January 1656, on Dresden Heath, 44 stags and 250 wild boar were killed; in Moritzburg in 1730 the bag was 221 antlered stags, 116 does, 82 fallow bucks, 46 fallow does and 614 wild boar; in 1748 in Wurttemberg during one hunt 500 animals were killed; in Bebenhausen in 1812 in one hunt alone, 823 animals were killed, including 116 stags. It is easy to see how this near-obsession with hunting led to the extinction of some species of big game in Europe. Not surprisingly, hunting on this scale led to an enormous demand for dogs. The Greek Philostratus refers to 'Indian' dogs in his description of a boar hunt. These were huge hunting mastiffs originating not from modern India but from Sumerian/Assyrian territory linked to the Euphrates and the Tigris and the north-east. Indian dogs were among the 2,400 hounds which paraded in Ptolemy II's procession. Marco Polo, when visiting the court of Kubla Khan in 1298, recorded that: "He hath two barons...the Keepers of the Mastiff Dogs...there are 2,000 men who are each in charge of one or more great mastiffs..." He was not of course referring to the Mastiff, the English breed, but powerful big game hunting dogs.

Nearer home, in Central Europe, big game was hunted using strong-headed hard-running 'hetzruden' or boar-lurchers. Duke Henry Julius of Brunswick was reputed to own the largest number of hetzruden, 600, in 1592. Whilst each castle featured its own kennels, the sheer numbers led to forcible boarding out. Shepherds were required to board at least one, in addition to their stock dogs, or their lambs were confiscated. In the 17th century, millers were required to board a specific number each year. Eventually over-hunting led to a vast reduction in boar numbers and a consequent reduction in hetzruden. In time, only small numbers of them were kept at the princely courts. Towards the end of the 19th century, they increasingly became the property of private citizens. The last of the Hessian dogs was sold in 1876. They were described as being fawn or red-fawn with black masks and muzzles, part-ancestors of today's Great Dane. In an earlier century, big game was sickeningly ‘baited’ for the amusement of sad audiences in Southern Europe, with most of the dogs misused in this way meeting a painful death.

"Hunting elephants with dogs! Impossible." This was the instant verdict of a colleague of mine in a discussion a few years ago. I gave my disbelieving colleague some extracts from Sanderson's 'Elephant Catching in India' of 120 years ago and he went very quiet! The value of dogs in elephant hunting was once well recognised. In his 'The Illustrated Natural History' of 1862-3, the Rev JG Wood wrote: "When wounded, the African Elephant is a most formidable animal, charging impetuously in the direction of the foe, and crashing through the heavy forest as if the trees were but stubble. In such a case, the best resource of the hunter is in his dogs, which bay around the infuriated animal, and soon distract his attention. The bewilderment which the elephant feels at the attacks of so small an animal as a dog is quite extraordinary. He does not seem to know what he is doing, and at one time will try to kneel on his irritating foes..."

Sanderson worked for the Forestry Commission in India and in his field-work often had to live for extensive periods in the jungle. He needed protection for himself and his workers and, as a keen sportsman, he naturally turned to dogs. His experiences and his advice on breeding the right dog for such a task are worthy of study. Sanderson was inspired by Sir Samuel Baker's experiences as recorded in his classic 'The Rifle and Hound in Ceylon'. Baker stresses the huge difference between hunting elephant in Africa to that in Asia, where the jungle leads to short-range confrontations. I discovered this myself whilst serving in Borneo, when a well-armed patrol from the Gurkha Brigade I was serving in was surprised by a charging elephant and a soldier killed.

Whilst building up his pack, Sanderson learned valuable lessons when encountering bear, bison, panther and wild hog, and especially when capturing a young wild elephant which "the pack seized without hesitation." He developed a pack of six seizers, that is holding dogs, nowadays represented by the perros de presa of Spain, the filas of Portugal and Brazil, the bull-breeds of Western Europe and the smaller mastiffs. The six comprised: a 'bullmastiff' of only 40lbs, two 'country-bred' bull terriers of around 35lbs and three young dogs from a mating of the first two. Sanderson wrote firmly that "show dogs are not required". The first elephant captured using the dogs was a two-year old weighing around 900lbs. The dogs seized the elephant by the cheek, the ears and the trunk, slowing it down sufficiently for men to approach and secure it with ropes. The elephant recovered quickly, its wounds healing in a week. It then joined Sanderson's department, working in the forests. One day, a recently imported Bull Terrier that had never seen an elephant before, met this one and without hesitation seized it by the trunk and 'held' it before being removed. The elephant was not harmed; the dog's instinctive behaviour and reckless courage being remarkable. This pack once engaged a panther, with only one dog being bitten, but not badly. I am not advocating hunting such admirable creatures – just looking hard at the dogs brave enough to face them when expected to do so.

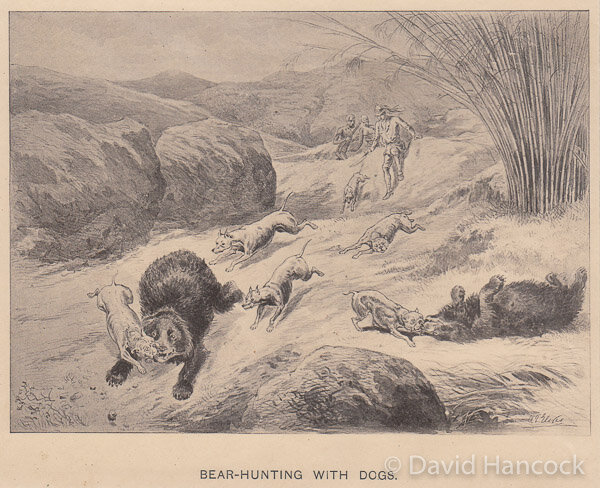

For use against panthers, Sanderson advised the use of a thick leather collar on the dogs, 3½" wide, and without spikes, writing that the presence of spikes made the quarry seek another vulnerable spot. He considered "two really good bulldogs a complete match for any bear". He went on to write that "When it is considered with what ease one good dog can pull down the largest tame buffalo or bullock, it may easily be imagined that a bison or wild buffalo has no chance against three or four." He did not use his dogs to kill animals but to 'hold' them, rather as practised by medieval hunters. His quarry was not savaged by his dogs but 'gripped' by them and slowed down. His trained dogs were rarely severely wounded.

He used his seizers only after the 'finders', usually terriers, had put up the quarry. The seizers were restrained on leashes until they were needed. This is in the mould of the 'bandogs' in early medieval hunting, which were leashed until the hounds of the chase had brought their quarry to bay. I do not support the theory that bandogs were merely 'tied-up yard-dogs' as some writers infer. Mastiffs were big game catch-dogs when respected as functional dogs, not bred to be massive and lacking agility; without agility a catch-dog would not live long. I have attended a Bullmastiff seminar where the breed expert on the podium claimed that only a dog weighing 120lbs could knock down and 'hold' a poacher. This despite the best night-dogs weighing around 90lbs and the recorded experiences of real experts like Baker and Sanderson.

It is disappointing to me that the Armed Forces and police service in Britain hasn't capitalised on the holding instincts of the mastiff breeds. At the Brazilian Army's Centre for Instruction for Jungle War at Manuas, Colonel Moniz de Aragao has been testing their national breed, the Fila Brasileiro, as anti-guerilla dogs. Having myself used Labradors and Alsatians in the Malayan Emergency, I know only too well how demanding such work can be for any dog. In Canada, Copeland and Alice Shavers have been testing their Filas for the exacting Schutzhund training and found them superb. Mastiff breeds like the Fila have a strong instinctive guarding nature; they just will not tolerate a threat to their family and property.

Another South American breed for catching big game is the Dogo Argentino, now being increasingly banned in Europe under the near-hysteria of the dangerous dog lobby. This breed was developed by two brothers, both doctors. One of the Drs Martinez spelt out the essential qualities desired in an Argentinian big game hound at a lecture in 1974. He wanted: a hound which did not give tongue until confronting its quarry; a hound able to seek air scent with a high nose, comparing this feature with that of the Pointer; a hound with scenting power ahead of sheer pace and a resolute animal, not afraid to tackle dangerous quarry. He stressed that a hound which could not 'seize and hold' its prey was valueless, mainly because of the immense physical demands made on hunters in the terrain favoured by the quarry. His dogs were used on puma and hog.

The Martinez brothers used Bull Terrier blood to instill gameness in their dogs. Sanderson, nearly a century before them, advocated much the same. He described his requirements as follows: "The seizers should be bulldogs or bull-mastiffs. In using the word bulldog I mean the dogs - usually bull and terrier - commonly termed bulldogs...The bulldog's determined courage and forward attack must be joined with the terrier's vivacity and intelligence." Baker's favourite seizer was sired by a 'Manilla bloodhound' or Cuban Mastiff, 26½" at the shoulder, with a girth of brisket of 34". He was alleged to have 'seized' at least 400 elk and boar.

We live in times when such a brave dog would be forcibly castrated and compulsorily muzzled in many allegedly civilised countries. Meanwhile the big game of Africa is being slaughtered by the lawless with Kalashnikovs whilst western so-called intellectuals campaign for more and more restrictions on controlled hunting. Most people who have seen big game in Africa hate seeing such animals in circus acts or zoo compounds. But for future generations this may be the only place to see them, as the big game species struggle to survive. Hunters like Sanderson, Selous and Baker had great respect both for brave determined dogs and the quarry they pursued.

Sanderson wrote: "The excitement of the sport consists in seeing the valour of the dogs...Nothing can be finer than to see the headlong attack of dogs that do not know what fear is. Some persons may take exception to the sport on the ground of cruelty to the dogs, but I do not think sportsmen will...they understand better what the dogs' feelings are." Some modern sportsmen, those only used to safe, sanitised sport, may not understand. Slaughtering masses of hares with shot-guns on an organized hare-shoot is not my idea of sport; there is no contest.

Nowadays, big game hunting is, rightly, very much restricted but has in some places been combined with necessary culling and some trophy-hunting. I am not an admirer of trophy-hunting. The crocodile I shot was a threat to the children of a kampong; the baboon I shot attacked a valuable war-dog. The Malayan honey-bear that lived in our infantry company location was a much-loved pet abandoned by its mother and fascinating to study. Honey-bears apart, there may be a future food source in big game. As the so-called, developed countries continue to raise diseased stock for uneasy markets, wild creatures not fed on recycled abattoir left-overs may find a market. This at least might ensure their survival. However, I can't see a future for, even as a 'dangerous sport', the bizarre pastime of 'stag-riding'; I might be tempted to send my clone to try it one day - purely, as the whalers say, in the interests of scientific research!