1181

FOOTHOUNDS – BASSETS & BEAGLES

By David Hancock

"...their heads are hung

With ears that sweep away the morning dew.

Crook-knee'd and dew-lap'd like Thessalian bulls,

Slow in pursuit, but match'd in mouths like bells..."

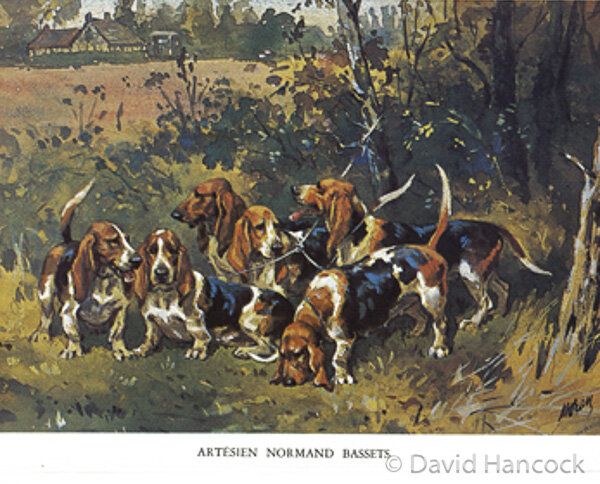

Those words of Shakespeare's, on hounds, from A Midsummer Night's Dream, make an apt summary of the appearance and performance of Basset-type hounds. The breed we know best in Britain is outnumbered by those of mainland Europe: the Artesian-Normand, the Bleu de Gascogne, the Fauve de Bretagne and the Griffon-Vendeen Petit and Grand. They are still used to hunt hare and rabbit for the gun, excelling in dense cover. But they are also used for flushing game birds, rather like spaniels. I suspect that the type evolved as a 'sport' from the St. Hubert Hound, in its various types, and was then committed to a hunt involving footed rather than mounted hunters.

In his most valuable book on hunting, published in the late 16th century, Jacques du Fouilloux makes an early reference to Bassets, describing them as badger dogs. He identified two types: those with a crooked front, which he stated were short-coated and went to ground better, and those with a straight front, which often carried the rough coat and ran game above ground as well as conducting terrier work. Du Fouilloux attributed the first home of these Bassets to the regions of Artois and Flandres. Both these regions have a record over five centuries of producing exceptional hounds.

In his excellent book on The Basset Hound (Popular Dogs, 1968), George Johnston, who knew his hounds, produced a map of north-western Europe showing the distribution of the basset type. This puts the rough-coated variety in north-west France (the Basset Fauve de Bretagne and the Basset Griffon-Vendeen), the smooth-coated variety in the north (the Bassets de Normandie, d'Artois and d'Ardennes) and the south (the Bassets de Saintonge and Bleu de Gascogne), with some smooth-coats on the German-French border in the Vosges and the Black Forest. He also mentions the allied breeds: the Dachshund in Germany, the Niederlaufhund of Switzerland and the Drever of Sweden. The first French dog show, in Paris in 1863, issued a catalogue which listed Bassets as follows: straight-legged short and long-haired, crooked-legged short and long-haired, Baden Bassets, Burgos, St Domingo, Illyrian and Hungarian Bassets. This shows a Basset diaspora stretching from Brittany to Budapest and from the Black Forest to the Balkans. The Baden Basset would have been the Dachsbracke or badger hound. The Danes had a Dachsbracke too, known there as the Strellufstover, and now embraced by the Drever of northern Scandinavia. These short-legged but usually straight-legged hounds were used to drive game to the waiting guns. It is surprising that, whilst the Swiss have developed several breeds of Niederlaufhunde, the French border areas with Switzerland have none.

The Basset Hound, as a pet or show dog, is now well established in Britain, with over 1000 being registered annually. In America in 1977, nearly 15,000 were registered with the AKC, such was their appeal. Other French Basset breeds are now becoming known here, with the Petit Basset Griffon Vendeen proving the most popular. This is hardly surprising for it is a delightful breed, full of character and charm. A first-class book on the breed has recently been published: written by Valerie Link and Linda Skerritt and published in America by Doral Publishing. Nearly 400 pages long, with a good index, it is a pleasing production in times when so many breed books are disappointingly shallow.

It is ironic that those with show Bassets who criticize the hunting fraternity for their outcross to the Harrier should choose to overlook pioneer breeder Millais's outcrosses to both the Beagle and the Bloodhound. Pure-bred Bassets are still represented in the hunting field by the Albany and the Huckworthy. Ten years ago, the West Lodge pack was ¾ Basset, ¼ Harrier but there were also Griffon-Vendeens in the pack. There are several packs of Petit Griffons-Vendeens hunting in Britain. The Ryford Chase has utilised West Country Harrier, Welsh Foxhound and more recently Beagle blood to make the pack less wilful and more biddable.

The Albany was for some time the Basset Hound Club's pack, with some show dogs hunting with them. The American hunting Bassets are often show dogs too. American hunters find two types of Basset Hound: those with high energy, which are lighter in bone, less chunky and longer in leg and the lower energy, more classic hounds which are noticeably more laid-back, in the modern idiom. The former lack the painstaking methodical style of the classic Basset hunt but often 'hunt on' using air scent before picking up ground scent once more. The Americans have trials for hunting in packs and hunting in couples or brace trials. The American Rabbit Hound Association also has a hunt competition for Bassets. In the future we may well have no Bassets hunting.

The Hunting Packs

In 1908 there were nearly forty hunting packs of Bassets in Britain, against just 10 Basset Hounds registered with the Kennel Club in that year. Twelve years ago there were ten packs recognised by The Masters of Basset Hounds Association. Six were straight-legged packs, the others crooked-legged. About half were pure-bred Bassets, the remainder mainly the so-called English Basset, the progeny of the Harrier outcross and more recently Beagle, West Country Harrier and Petit Basset Griffon Vendeen blood too. The first pack made up of English Bassets was the Westerby, whose country lies mainly in Leicestershire, and originally pure-bred Walhampton Bassets. The pure-bred hunting basset lacks much of the excessive wrinkle and exaggerated crooked knee of so many show bench hounds. The Fourshire Bassets of ten years ago were good examples of pure-bred working hounds.

Around 1910, the hunting stock declined appreciably, all too many of the hounds displaying gross exaggeration and even malformation. There were stories of Bassets being carried from the hunting field on stretchers made of sheep hurdles. In 1911 The Masters of Basset Hounds Association (MBHA) was formed and only hounds from recognised packs became eligible for registration. KC-registered hounds were refused entry. The majority of MBHA registrations were Artesian-Normandie in origin. A notable exception was the Sandringham kennel of Basset Griffon-Vendeen owned by Queen Alexandria. But the First World War almost saw the demise of the Basset Hound in England.

Colonel Morrison's work with the Westerby pack from the 1930s saw a steady improvement in fortune. He started with the Basset Artesian-Normandie for its nose and cry, that is, its scenting skill and musical baying. He made inspired crosses with the Basset Griffon-Vendeen, the Beagle and the Harrier to enhance drive, stamina and pace. Today's show breeders should note that the improved performance was not vaguely 'expected' from a closed gene pool but pursued by a gifted breeder with an open mind. Millais, the pioneer Basset breeder would have approved.

Avoiding Excessive Features

A writer in the Veterinary Record thirty or so years ago, referred to this type, rather unkindly, as 'achondroplasic dwarfs'. Smythe, in his excellent The Conformation of the Dog (Popular Dogs, 1957), writes: "Some breeds exhibit localized deformities; in the Dachshund and Basset Hound the head and body are normal but the limbs show exaggerated achondroplasia. Legs are short, thick and somewhat crooked. Both the head and the limbs are encased in a skin several sizes too large for the dog, with wrinkled folds. The feet are large." Achondroplasia is a form of dwarfing due to disease affecting the long bones of the limbs before birth; it occurs in cattle and in other breeds of dog. When it is undesired in a breed of dog, the afflicted pups are quickly destroyed.

The inheritance of short legs is complex; Robinson (1989) suggested that shorter legs are dominant over longer legs. He went on to state: "Although polygenic heredity may be assumed for length for most breed differences, this does not mean that major achondroplasic genes do not exist." The worry here for me is that shorter-legged breeds can in time become even shorter and not always for the benefit of the breed. Crooked legs can so easily become painfully crooked legs. It is significant that when the Bassets used for hunting in Britain became too exaggerated, it was the leggier Harrier which provided the best outcross, rather than the Beagle, which was also tried. I believe that Basset Hounds, pure-bred and true to type, in France, Britain and America, have occasionally produced a large hound pup, with straight proportionately long legs, in an otherwise typical Basset litter.

If you respect and admire functional dogs, then it is with sadness that you might view some Bassets on the show bench. There is all too often a poor lay of shoulder, a short upper arm, a looseness of elbow, flat feet or even splay feet and a lack of a ribcage carried well back. Even more apparent are the over-long ears and the over-bent front legs. A cynic might observe that the Basset Hound is a breed much loved by the nation but not so much by some of its breeders. There is a balance to be found in such a breed between breed type and a degree of gross exaggeration which causes discomfort to the dog. Breed lovers should be dog lovers too.

“To the Editor of the Kennel Gazette,

Sir, BASSETHOUNDS, Would the exhibitors of the above hounds pardon my ignorance, and kindly inform me whether the bassethounds as exhibited at the late Kennel Club show are intended to be used as ‘sporting dogs’, in which category I see they are classed, or if they appeared as an advertisement for hounds fatted for show purposes, and as such, no doubt, splendid specimens? Being of a ‘sporting’ turn of mind I thought I should like to possess a small pack of these dogs, but the appearance of those at the show has quite damped my ardour, as for hunting purposes those dogs could only be of use to one afflicted with the gout, or otherwise incapacitated from the active use of his legs.”

From The Kennel Gazette, March, 1888.

The sentiments could have been expressed by a sportsman of today; but The Kennel Gazette of today would not print such a letter – any criticism of the pedigree dog is forbidden in this journal. I wrote articles for it for five years, then dared to express a view, in another magazine, that opposed KC thinking at that time, and was never to write for them again. Sycophancy or blind loyalty can never be in the best interests of dogs.

The Beagle

“Pour down, like a flood from the hills, brave boys,

On the wings of the wind

The merry beagles fly;

Dull sorrow lags behind:

Ye shrill echoes reply,

Catch each flying sound, and double our joys.”

Those words by William Somerville capture the sheer gaiety of the hare-hound called the Beagle. But for how long in years to come will ‘the merry beagles fly’ and we go ‘hare-ing after them’? In Robert Leighton’s New Book of the Dog, published in 1912, GS Lowe was writing: “There is nothing to surpass the beauty of the Beagle, either to see him on the flags of his kennel or in unravelling a difficulty on the line of a dodging hare. In neatness he is really the little model of a Foxhound.” He went on to point out that ‘Dorsetshire used to be the great county for Beagles. The downs there were exactly fitted for them, and years ago, when roe-deer were preserved on the large estates, Beagles were used to hunt this small breed of deer.’

Rough-coated Beagles

He recalled the Welsh rough-coated Beagle and its look-a-like, the big Essex Beagle, going on to state that ‘A very pretty lot of little rough Beagles were recently shown at Reigate. They were called the Telscome, and exhibited by Mr. A. Gorham.’ He suggested Welsh Hound or even Otterhound blood to get this coat and the increased size of the Welsh and Essex varieties. But from his illustration of Gorham’s hounds, a distinct Basset Griffon Vendeen (Grand) look can be detected. An interchange of French and English or Welsh hound blood has centuries behind it. Coat texture apart, the Gorham Beagles have the set of ear, ear length and facial expression of the French hounds. Beagle breeders would have known of these 16inch high Griffons and, to avoid introducing much greater size, would have seen much merit in resorting to the blood of the Basset Griffon Vendeen (Grand).

In his Rural Sports of 1801, the Rev WB Daniel wrote: “Beagles, rough or smooth, have their admirers; their tongues are musical, and they go faster than the Southern hounds, but tail much…they require a clever huntsman, for out of eighty couple in the field during a winter’s Sport, he observed not four couple that could be depended on. Of the two sorts he prefers the wire-haired, as having good shoulders, and being well filleted. Smooth-haired Beagles are commonly deep hung, thick lipped, with large nostrils, but often so soft and bad quartered, as to be shoulder-shook and crippled the first season they hunt; crooked legs, like the Bath Turnspit, are frequently seen among them…” ‘Shoulder-shook’ is an old hunting field expression for the jarring caused by badly-placed shoulders and is an apt one. There is no hint of a uniform breed of Beagle in this passage.

Daniel also considered “The North Country Beagle is nimble and vigorous, he pursues the Hare with impetuosity, gives her no time to double, and if the Scent lies high, will easily run down two brace before dinner”; he went on to describe a pocket Beagle, writing: “Of this diminutive and lavish kind the late Colonel Hardy had once a Cry, consisting of ten or eleven couple, which were always carried to and from the field in a large pair of Panniers, slung across a horse; small as they were, they would keep a Hare at all her shifts to escape them…” So, we have smooth, rough and wire-coated Beagles, some with crooked legs and some of small terrier size, i.e. pannier-size. There was clearly no attempt to seek a standardized breed, just a competent hare-hound of varying coat texture and shoulder height. The country being hunted often dictated the size of hound, but performance was everything, never appearance alone.

Shoulders and Size

There seems to be an endless debate about shoulder height in Beagles. Writing in Hounds magazine in November 1987, Beagle expert Newton Rycroft gave the view that: “Height alone does not govern pace in beagles. Shoulders and stride are also most important.”, going on to describe how one of the smallest bitches in kennels often performed best in the field because she was the only one with perfect shoulders. He finished his article by stating: “Finally, the 16-17 (inch) beagle. Rightly or wrongly those who breed these get little sympathy from this quarter! If they cannot catch hares with 15-inch beagles then I feel they need not bigger hounds, but better ones.” In another issue of the same magazine, ‘Hareless’ was stating “Reduce your size down to 14/15 inch? Well. fine in the lowlands, but too small for a rough moorland country. Quality fifteen inch beagles can soon lose their followers on the right day, but as long as they turn with their hare and retain a god cry do not be put off by the grumblers. It seems illogical to spend ten to fifteen years breeding your hounds to perfection, then start taking notice of people who say they are too good.” I do wish the breeders of show Beagles would start taking notice of those who breed the hunting hounds.

Hunting a Pack

Ever since reading Roger Free's Beagle and Terrier as a fourteen-year old, hunting with a small pack of assorted dogs, has appealed to me. He wrote in times when individual freedom had greater respect but a future need for vermin-control could see his style of operating in the field on the way back and to a greater degree. Free kept and hunted a small mixed pack of 14" Beagles and Terriers for hunting rabbits for the gun. 'Dalesman' described Free's pack as one "which any huntsman might be proud, because they have all those attributes which go towards excellence. Some of these are bred in the hounds -- courage, stamina, nose and tongue -- but the rest must be taught and instilled with patience and knowledge of hounds and their work." But what a challenging self-set task for any ambitious sportsman. Free, not surprisingly, considered that more pleasure was to be derived from hunting your own hounds than from being a follower of a pack hunted by another.

Pack Instincts

Free argued that whereas gundogs are taught by man, scenthounds frequently learn to hunt without the assistance of man and are therefore more self-reliant. He wasn't decrying the merits of gundogs but stressing the need for a different approach to the training of hounds. He advocated choosing a dog that was not afraid to look you in the eye. He preferred to guide a dog rather than 'break' it. He looked for boldness, perseverance, eagerness and biddability. He emphasised the latter and was aware of the menace of self-hunting hounds, oblivious to all recall.

Free concentrated on hunting the hounds and did not himself carry a gun. He normally used four or five couples of Beagles with two or three terriers, finding the latter better in really difficult cover. This meant handling a dozen dogs singlehanded, a testing task. Some sportsmen find controlling one gundog quite beyond them! Generally speaking, terriers and scenthounds demand far more skill in their training than gundogs, partly because of their different instincts and partly because they are often expected to operate in the field as a pack Gundogs have been bred for centuries to respond to human direction in the field; terriers and scenthounds have striven for several centuries to defy all human instructions.

In the United States, the American Rabbit Hound Association registers rabbit hounds bred to meet its standards. Founded in 1986, with 140 clubs in over 28 states, the ARHA promotes hunting competitions and offers a programme of organised rabbit hound hunts. There are six types of hunt competitions: gundog brace, gundog pack, big pack, little pack, progressive pack and Basset. The objective of these field events is to identify those hounds with the best ability to search (i.e. locate the rabbit), flush and drive the rabbit back to the hunter. At the end of each hunt competition, there is a conformation show to try to identify the best constructed hounds. A comparable parent body here might concentrate the minds of rabbit-hunters.

Value of Rabbit Control

In Australia they have an even bigger problem with rabbit-damage than we do here. Yet, despite developing their own heeler and terrier, they too have never produced a specialist rabbit hound by name. This may be because the breeds taken there from Britain were deemed adequate for the task. In his informative book Australian Barkers and Biters of 1914, Robert Kaleski paid tribute to the Beagle, writing: "Of late years another job has arisen for the Beagle in Australia, and he, like all good Australians, has risen to the job. This job is a very important one. Every grazier knows that after his country has been absolutely swept bare of the grey curse there is invariably one here and one there overlooked in some inaccessible places which pop up and start breeding again. Ordinary dogs do not bother with odd ones like these in bad places; but the Beagle, with whom chasing rabbits is an age-old instinct, goes after these 'last rabbits' with joy and never leaves them alone until run down and secured."

It is this sheer persistence, massive enthusiasm and scenting prowess which makes the Beagle such a superlative hunter - and a handful sometimes for a novice Beagle owner not versed in their avid trailing instincts whenever strong scent is encountered! These instincts are being perpetuated by the working section of the Beagle Club and I applaud their efforts in these difficult days for sporting breeds. The best Beagles that I see come from the Dummer pack, they always look capable of providing a great day’s sport and appearing far racier and more workmanlike, yet still handsome, than those in the KC show rings. The show exhibits for me possess too much bone, walk too stiffly and are often heavy-headed. A recent Crufts critique stated that the most prevalent fault in the entry was wide fronts and what was termed ‘flapping feet’; short steep upper arms were reported at a number of Championship shows, a certain cause of restricted movement. The judge at the Welsh Beagle Club’s November 2009 show wrote ‘I am saddened by the state of the breed at present particularly in males…I found many exhibits with large splayed feet and, accompanied by a weakness in pastern…’ This is not good news for any hound breed.

Long Distance Runner

In his informative book Beagling, Faber and Faber, 1960, Lovell Hewitt, makes some instructive points on the construction of the little hound. He considered that Beagles were all too often judged on their fronts and criticized the desire for absolutely straight front legs. He pointed out that Squire Osbaldeston’s rightly famous stallion hound Furrier 1820 was only drafted to the Belvoir because he was not quite straight in front. He stressed that the Beagle was a long-distance runner not a sprinter, emphasizing the importance of strong well-muscled loins and quarters. He wrote that Beagles tend to become weedy with successive generations and a narrow chest was a warning of this. He liked the fuller waist and disliked dippy backs. He found that a hound with a short head also lacked persistence. He was strongly against the exaggerated cat’s foot, once the preference in the hunting kennels.

In Sweden, Switzerland, Norway and Finland, the Beagle is a popular dog for hunting; the Swedish Beagle Club being founded in 1953. In these Nordic countries the Beagle is hunted singly not in a pack and not just on hare; in addition to hare, in Finland on fox, in Sweden on fox and roe deer and in Norway on fox, roe deer and deer. Each year around 300 entries at field trials are made in both Sweden and Finland. In Sweden a Beagle cannot become a show champion unless it first gains the field trial champion award. In Britain, Beagles from the show world can gain a working certificate; for the packs there used to be beagle trials like the West Country Beagle trials in March each year. Perhaps it’s time for another Charlie Morton! He hunted a small pack of Beagles solely for rabbiting with the gun, from about 1877 to 1919; his pack consisting of three couples of sixteen-inch hounds and often producing returns of over seventy rabbits a shoot. He never carried a horn, just used his rich deep voice. He worked his hounds two or three days a week but insisted on a day’s break between shoots. He never used a van or a hound trailer, walking his hounds to each meet. Many of his hounds lived to well over ten and he hunted his pack for over forty years. Local farmers greatly valued his work on rabbit-control; rabbit damage in Britain nowadays costs our economy tens of millions of pounds. Bring back the Beagle rabbit-hunts!

“Since starting these annual shows at Peterborough and the formation of the stud-book, a marvellous change for the better has taken place in both the harrier and the beagle, but in the present instance, of course, my remarks must be confined to the latter. No beagle can now be entered in the stud-book with a direct harrier cross nearer than two generations back. Under the association, classes are arranged at the annual show for beagles not over sixteen inches which are entered in or are eligible for admission into the stud-book, and during the year 1893 there was a strong entry of these hounds. Leaving the association, I will endeavour to describe the best kind of beagle for hunting the hare, and I may remark that the little beagle of about twelve or thirteen inches, very pretty, and useful for rabbit hunting, is absolutely of no use whatsoever.”

From Hunting by the Duke of Beaufort (and seven other hound experts of that time), 1894.

“To sum up, therefore, which we should look for in our favourite hounds are perfect symmetry of build to insure strength and staying power, an intelligent and alert expression, a shapely neck, well-balanced shoulders, a compact sturdy body with good depth and width of chest, well-rounded and muscular loins and thighs and straight well-boned forelegs with perfect cat-feet. Of faults silently to shudder at, when seen in a neighbouring pack, and to turn a blind eye to, if seen in our own, are tendencies to straight shoulders, flat open splay feet, short throaty bull-necks, weak thighs, slack loins and flat sides, while knock knees with knees turned in and toes out or calf-knees with knees over-extended and actually bent slightly backwards, cannot fail to make us groan aloud in any circumstances in sympathy for the poor hound which possesses them.”

From Beagling for Beginners by Dr. D. Jobson-Scott OBE, MC, MD, Ch B, Hutchinson, 1933.