1184

The GOODBYE GREYHOUND

By David Hancock

Once coursing was banned the breed of Greyhound was destined for eventual decline. As a pedigree breed, exhibited in show rings, it has lost favour: 212 in 1926, 52 in1956, 49 in 2005, 30 in 2012 and 41 in 2016. As such it is an endangered species. On the racing track, as the sport declines, Greyhound numbers fall. There are now more Greyhound-lurchers than purebred Greyhounds; the latter have no recognised purpose - we need a new form of the Waterloo Cup, the Blue Riband of sighthound tests. This new form could not involve the pursuit of live hares, but rather as on the track, the pursuit of a mechanical 'hare', in this case a specially-designed drone. This 'hare' could be chased at great speed by a brace of hounds, be manoeuvred across country, twisting and turning, in a competition run, roughly, under the old National Coursing Club's rules. All the sighthound breeds could compete; each one would benefit hugely from a cross-country trial of their physical soundness, a far more searching examination than any conformation dog-show. There are plenty of rich betting firms to sponsor such a trial. The once massively-contended Waterloo Cup could be awarded once again. This alone could revive the breed of Greyhound.

The sighthound breeds came to us from the sporting field, from being used as coursing hounds; they will only stay with us as real sighthounds if we retain a sporting use for them, whether it’s on the track, on the lure or after a drone. We owe a great deal to those coursers who bequeathed such remarkable hounds to us; we will only honour their memory by using them. The very expression ‘companion dog’ hints at the dog being there for our benefit but to regard a sighthound purely as a pet is to insult its distinguished heritage; we really must use them. I think it is fair to claim that coursing, however casually-conducted, all over the world, shaped the sighthound breeds of today into formidable canine athletes. To maintain the sighthound’s long history in providing such excellence is going to prove a challenge. Lure racing is valuable exercise; track racing tests sheer speed and bend handling skills but coursing was the supreme test. All sighthounds need to run, but the fast and agile pursuit of prey at speed in the hunting field is their instinct.

But the whole purpose of hare-coursing was as a competition between the hounds not the catching of the hare. As Arrianus Flavius put it in 150AD: “The aim of the true sportsman with hounds is not to take the hare, but to engage her in a racing contest or duel, and he is pleased if she happens to escape.” Those words, from two millennia ago, capture immediately the ethos of coursing across the centuries: it never has been about two hounds striving to catch a hare but a brace of sighthounds striving to outrun each other. The quarry is respected, allowed a fair start or law, and unlike shooting or fox-hunting, permitted to escape at any stage during the chase. In his An Encyclopaedia of Rural Sports of 1870, Delabere Blaine wrote: “The practice of modern coursing may be dated from the time of Elizabeth. Under her auspices it became a fashionable pursuit; nor has time diminished the hold it took on the regards of the sporting public. To further, methodise, and give stability to its practice, a code of laws was framed by the Duke of Norfolk, himself a lover of the leash, that became the stock on which the rules observed at coursing meetings were ingrafted.” Another Norfolk landowner Lord Orford started a line of coursing Greyhounds of remarkable prowess.

Orford’s Czarina won 47 matches without ever being beaten; when Orford died, she went, with her co-star son Claret, to the Yorkshire kennel of Colonel Thornton. Claret was put to a high-quality bitch owned by another Yorkshire coursing man, Major Topham, to produce three of the best Greyhounds ever seen: Snowball, Major and Sylvia. All three won every match for which they were entered. Snowball was considered to be the finest Greyhound ever bred; he won in every type of country, was famed for his stamina and for his sheer power when running uphill. This blend of Yorkshire and Norfolk blood started perhaps the best-ever line of coursing Greyhounds from England and provided the breeding basis for the breed from then on. Snowball sired nearly fifty litters, with the bitches coming from all over Britain. Forty years after Snowball’s whelping, the ‘Blue Riband of the Leash’, the Waterloo Cup, was held at Altcar and from then on, this cup was the pinnacle of coursing fame. It was run on ground where the hare was protected and almost revered.

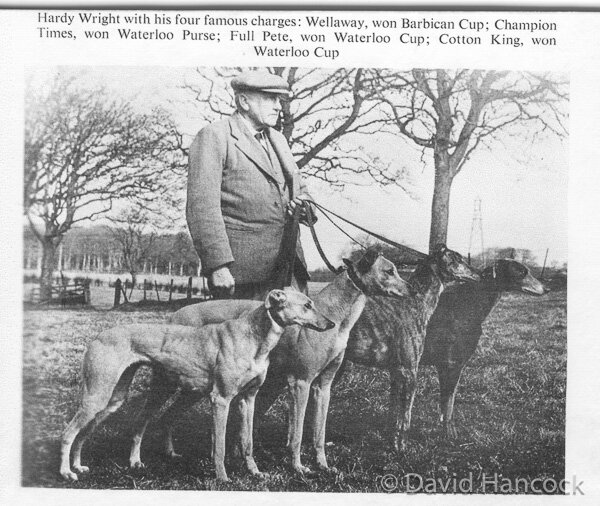

In the coursing world, celebrated names like Lords Lurgan, Rivers and Orford, Colonels Dennis, North and Thornton and Edward Dent, but remarkable families especially, crop up. From the 1880s to the 1900s, the Wright family stands out. Edwards Clarke, the great Greyhound expert, admitted he learned most from them. Joe Wright trained the Waterloo Cup winner of 1888: Burnaby and the 1895 winner: Thoughtless Beauty. This latter final saw Joe Wright the trainer of the winner, a younger brother Tom the trainer of the runner-up, and another brother, Robert, acting as slipper for the contest. Tom trained five winners of this famous cup, for the Fawcetts and their famous ‘F&F’ kennel: Fabulous Fortune (1896), Fearless Footsteps (1900 and 1901), Farndon Ferry (1902), Father Flint (1903) and Fighting Force (1923), a quite stunning record for any sporting family. Farndon Ferry and another dog from the same kennel, Fiery Furnace, were considered by Edwards Clarke ‘to be the tap-roots of all Greyhounds that have either coursed or raced in the twentieth century’. Harold Wright trained Dee Rock, the Waterloo Cup winner of 1935. The Wrights, between them, possessed enormous knowledge of Greyhound training, conditioning and welfare, and especially, their health care. Will we ever see their like again? The loss of such immense expertise from the sporting dog scene, without new blood coming through, is hugely worrying.

Many parts of England achieved fame for their locally-bred Greyhounds; renowned at various times were the High Wolds of Yorkshire, the farms of Cornwall (especially for the early show dogs, especially from the famous exporter of Greyhounds to America, Harry Peake), the flat fenland of Cambridgeshire, the Sittingbourne area of Kent, from where the earlier King Edward took Greyhounds to hunt in Gascony, and the East Riding of Yorkshire, where it was claimed the stock were the descendants of the wolfhounds once used there to hunt down the remaining wolves of England. The Lancashire dogs, like those of the Fawcetts, were often trained on the Fells to increase stamina; the Norfolk dogs were renowned for their long-distance sprinting powers.

The Wiltshire dogs had their own imprint and reputation – well into the twentieth century, with the highly successful ‘Melksham’ kennels of Henry Sawtell, which were at Shaw, near the town of that name. Melksham Tom was the fastest dog of his day and the sire of more coursing winners than any other dog of his time. This dog was sired by Staff Officer, who produced four out of five Waterloo Cup winners between 1921 and 1925. Melksham Tom’s sheer pace was legendary but he was not always a great winner – on his debut at Avon Valley he led by seven lengths but was still beaten. His two sons, Melksham Endurance and Melksham Denny ran successfully in Ireland, where their father retired to stud in 1925. All three were very handsome dogs, very symmetrical and sleekly muscled but not huge dogs. All these renowned kennels were essentially rural and greatly respected in their respective counties.

Out of coursing came the urban equivalent, track racing. As long ago as 1876, mechanical lure racing was conducted, at first as a spectacle at a sporting show, when two Greyhounds pursued an artificial hare raced along a groove in the track, over a 400-yard grass track. The first race was won by Charming Nell, owned by Edward Dent, breeder of the famous coursing Greyhound Fullerton. But it was interest in America that spread back to Britain, so that from the mid 1920s this new sport took off. In 1926 the average crowd at a track meeting was 11,000. By 1932, the attendances had reached 20 million. With big money now accruing from the sport, the tricksters soon moved in, with doping scandals rife. The National Greyhound Racing Club has worked hard to drive out match-fixing and dog-faking.

In their account of the first London greyhound track meeting, The Times of June the 21st 1927, reported: “The card consisted of eight races. The finishes, perhaps, were not quite so close as usual, but cleverness and experience told nearly every time, and the keenness and gameness of the dogs were indicated, first, by their howling and pawing at the doors of the starting box and, then, by their refusal to give in so long as a breath of wind remained to them. Trainers already tell stories of the older dogs’ hatred of being beaten by another dog – a hatred that far transcends the desire for the mechanical hare’s blood.” It is unwise to underestimate the powerful instincts of the sighthounds, especially their eagerness to run after a moving quarry and, most unwise to under-rate the sheer competitiveness of the speedsters. However aloof their demeanour, however gracious their movement and however reserved in nature, these dogs are ‘hot-wired’ to run and to win!

A Greyhound can cover 5/16ths of a mile in 30 seconds. In each decade the feats are repeated: in 1932, Ataxy did 525 yards in 29.56 seconds, and, in 1936, 725 yards in 41.69 seconds. In 1971, Dolores Rocket did the 525-yard course in 28.52 seconds. In 1944, Ballyhennessy Seal set what was then a new world record for 500 yards in 27.64 seconds. The legendary Mick the Miller did the 600 yards in 34.01 seconds in 1930. He was spoken of as combining 'tranquillity with trackcraft'. In other words, he never wasted energy nervously and used the circuit cleverly. When he died, he was found to have a heart weighing 1½ ozs above the normal for a Greyhound of his size.

Of course, hounds with a comparable build can also achieve great speed; a 32lb Whippet was once recorded as covering 150 yards in 8.6 seconds. This build is a superb combination of bone and muscle, a unique balance between size/weight and strength and quite remarkable coordination between fore and hind limbs. The Greyhound sprints in a series of leaps rather than running in a strict sense. It is what is termed a 'double-flight' runner, where the feet are all off the ground at the same moment. This is unlike a 'single-flight' animal like the horse which, when racing, always has at least one foot on the ground.

As with most breeds of dog, prejudice, often based on ignorance, can undermine a breed. In Greyhounds, three have influenced breeding plans: weight, colour and a refusal to acknowledge outstanding dogs with no provenance or ‘papers’. The weight of successful coursing Greyhounds is worth a glance. The renowned Coomassie was 42lbs, Sea Cove, winner of the Cup in 1870, when Master M’Grath didn’t run, was 50lbs, the handsome Cerito, 3 times winner of the Cup, was 51lbs, the remarkable Master M'Grath was around 53lbs, Bit of Fashion was 54lbs, Golden Seal, Staff Officer, Guards Brigade, White Collar and Fitz Fife were each around 65lbs but Shortcoming only 49lb. Our show Greyhound has no stipulation regarding weight but its ideal height, for a male dog, is desired at 28-30 inches. A Deerhound dog of 30 inches at the withers would weigh around 100lbs. Does a Greyhound need to be 30" high and approaching a hundredweight? Why does a show Greyhound need to be twice the weight of a successful coursing Greyhound? The American KC standard sets the Greyhound's weight at 65-70lbs for a dog and 60-65lbs for a bitch.

On the question of colour, at times the colour brindle was frowned on out of fear of Bulldog blood being present, after Colonel Thornton’s infamous outcross to instil enhanced determination. The brindle Fullerton’s remarkable feats put this one to rest. At another time, a white coat was thought to alert the hare to the pursuing hound’s approach and not favoured. The outstanding hound Snowball was depicted by Chalon in a black jacket, some say to meet such prejudice; it was actually named after its coat colour! Black hounds were considered lucky. Farmers and more rural coursing men would use breeding stock without papers, or even resort to the blood of highly-effective ‘Greyhound-lurchers’ to improve their stock. When are sporting dog-breeders going to strive to breed, not on breed-purity, but on performance? They are perpetuating dogs with a purpose, not cat-walk models.

Long ago, in the early days of showing, running dogs were shown: the winner of the Waterloo Cup in 1855, Judge, won second prize at the 1862 Islington conformation show. Twenty-five years later, Bit of Fashion, dam of the celebrated Fullerton, was exhibited at Newcastle, winning first prize. I find it hard to believe that a specialist Greyhound judge would not admire the powerful hindlimbs, strong sloping shoulders and rounder rib cage of the sporting type. All Greyhounds were once like this; where is the rationale of being attracted to a breed and then wishing to change its shape? Symmetry, gracefulness and beauty are not the essence of a sporting breed. In depictions of sporting Greyhounds, whether on canvas or on film, the muscular loins stand out. Show Greyhounds look statuesque. I have seen some impressive specimens however from the Shalfleet and Ransley kennels.

In The Kennel Gazette of April, 1891, the report covering the Greyhound entry at the Kennel Club’s 35th annual show contained these words: “These were far larger classes than usual at Kennel Club shows, and were particularly interesting from the fact of Col. North’s entries of Huic Holloa and Gay City for competition, and Fullerton, Young Fullerton and Simonian not for competition. Five dogs of a similar high running form have never before been seen at a dog show. Fullerton is a very much better-looking dog than ever Master M’Grath was, showing more quality and much better made in front. He was exhibited in most perfect condition, full of muscle, and his feet and legs were a treat to see; in this respect Young Fullerton is also very good, although of course he has not the power of his older brother. Simonian is a beautifully topped dog with immense quality, but his feet will never stand the work of either his brothers.” At this show the top coursing dogs were on show from the leading coursing kennel of the time. The sentiment behind the report was the crucial link between function and form.

In the Kennel Gazette of July 1888, the Greyhound critique made mention of 'a showy black, but flat in ribs...' and a bitch of 'beautiful quality and style, but decidedly short of heart room...' Does ‘showiness' compensate for flat ribs? Can a sighthound, designed to run very fast, combine beautiful quality with a lack of heart room? Five years later, a critique praised a 'niceish' black bitch with 'rather upright shoulders' (which came second!) and the reserve card winner a 'pretty' dog 'somewhat cow-hocked'. A critique on the breed just a year ago stated that front movement was really bad, with another observing that muscle tone was very hard to find. A recent Crufts critique on the breed commented on the absence of muscle tone in the entry. This is depressing. What is even more depressing is the wording of the Breed Standard under the sub-heading: Characteristics. The words following this sub-heading merely read: ‘Possessing remarkable stamina and endurance’. No mention of speed! Kennel Club! Kennel Club! This is the fastest breed in the world over middle distances. It has to be able to turn at great speed. It has to have immense determination. Say so!

The show Greyhound fanciers might argue that they never expected their hounds to compete at the Waterloo Cup. But that argument is destroyed by the wording of their breed standard. This is a breed clearly designed to run fast, very fast. The section under 'Gait/Movement' asks for a "Straight, low-reaching, free stride enabling the ground to be covered at great speed. Hindlegs coming well under body giving great propulsion." The need for a good slope to the pelvis to allow great forward extension in the hindlegs is not mentioned. A show Greyhound is expected to be: strongly not finely built, upstanding i.e. have presence, generously proportioned – a curvaceous rather than an angular dog, a dog of substance with great suppleness of limb, a clearly defined torso and be muscular without being loaded. The hindquarters should hint at great propelling power and the foot should not be too cat-like but more hare-footed than many judges deem necessary. The dog should be a graceful mover and a genuinely handsome dog. But in essence it is a hunting dog!

A judge’s critique from a 2011 Greyhound Club conformation show, after stating that many of the entry carrying too much weight that affected movement and the elegance the breed should have, went on to comment: “I feel for the racing owners as they strongly support the breed at all levels; although all Greyhounds come from the same foundation stock, the racing dogs simply do not conform to the show standard (i.e. the written Breed Standard, DH) and are usually placed down the line…” In other words, dogs that are useful are less valued! In 1928, the Greyhound Primly Sceptre won Best-in-Show at Crufts, the first to win the new award. Racing Greyhounds have been regularly shown and entered for Crufts, perpetuating a long tradition. In 1929, the entry was 252 from 187 Greyhounds, of which only 17 were show bred, the coursing entry prevailing. Ernest Gocher’s brindle 70lb dog Endless Gossip is the most famous racing Greyhound to appear at Crufts; he won the 1952 Greyhound Derby and performed well at the 1953 Waterloo Cup. An outstanding show Greyhound, Treetops Golden Falcon, won Best-in-Show at Crufts in 1956, only the second member of the breed to win this supreme award. It is good to learn that Ireland’s annual Dublin show is to schedule special racing Greyhound classes, with each of the 22 tracks asked to send one dog to compete. At Crufts in 2009, in the racing/coursing entry, there was a striking black bitch Luvina Lexine Lacers Louise, which perfectly exemplified the correct conformation for the breed.

We are now faced with an unprecedented challenge to our sighthound breeds, the law of the land is against the function for which they were bred and used for - for several thousand years. When a highly-regulated field sport becomes proscribed, unregulated illegal hunting, with no respect for the quarry, replaces it. This will be a disaster for our wildlife and a major setback not just for sighthounds but for the quarry species too. But in the time it takes to realise legislative folly and then restore sanity to the scene, what can we do to preserve Greyhound skills? Track racing, lure-chasing and drone-pursuit matches need to be supported; these superlative hounds need to be tested, if only to identify the best breeding stock. All lovers of the Greyhound breed need to seek outlets for their hounds; the regulated cross-country pursuit of mechanical hare-drones could provide the best answer. In rural communities, the skill and sporting instincts of the Greyhound are being perpetuated in the Greyhound-lurcher, a hybrid where the Greyhound physique and sporting nature is being conserved. Long may they run!