1185

ARMOURING THE DOG

By David Hancock

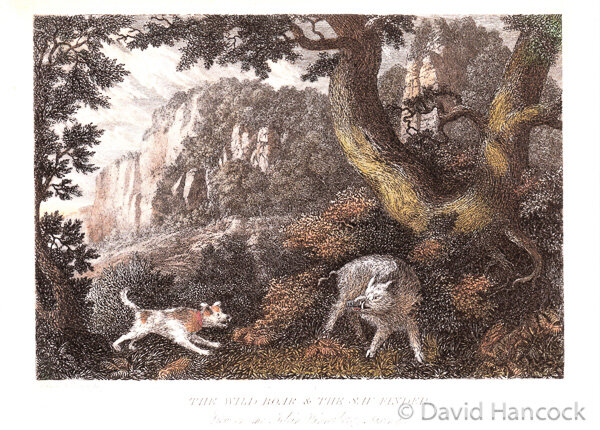

If you look at prints, engravings and paintings of hunting scenes in medieval northern Europe, you can soon detect strong-headed, mastiff-type dogs or 'matins', usually depicted at the kill of the quarry concerned: boar, stag, bison, even aurochs. Such dogs were clearly in wide use and yet few survive as recognised breeds. The boar hound, used as a hound of the chase, lives on as the Great Dane, known in Germany as the Deutsche Dogge or Ulmer Dogge, with the noun being used to denote, not a broad-mouthed dog or killing mastiff/holding dog, but a hunting mastiff or par force hound. The boar lurcher, or less carefully-bred catch-dog, one type of which developed into the German bullenbeisser, is arguably represented by today's Boxer, albeit in reduced size, more uniform type and a less coarse appearance. When far too many valuable dogs were killed by their quarry, protective coats were improvised to afford some sort of tusk, antler or horn guard.

In central Europe there were once huge dogs used in the boar hunts of the great forests of what is now Germany, western Poland and the Czech Republic. They were known as 'hatzruden' or ‘hetzruden’ (literally big hunting dogs), huge rough-haired crossbred dogs, supplied to the various aristocratic courts by local peasants. They were the "expendable" dogs of the boar hunt, used at the kill. The nobility however bred the smooth-coated 'sauruden' (boar hounds), also referred to as 'saufanger' (boar catcher, one was shown in England in 1893) and 'saupacker' (literally, member of a pack used for hunting wild boar). The 'sauruden' were the equivalent, in the late 18th century, of the hunting alaunts of the 15th century, with the Dogo Argentino being the modern equivalent of the "alaunts of the butcheries". The specialist 'leibhund', literally 'body-dog', was the catch-dog used to close with the boar and seize it. I believe it is perfectly reasonable to regard the modern breed called the Great Dane (in English-speaking countries) or Deutsche Dogge (German mastiff) as the inheritor of the saurude or boar hound mantle. This breed should be named (and judged) as a hound if its historic role is to be honoured. Our Kennel Club persistently refuses to recognise the Great Dane as a hound. The kennel clubs of the world have made no attempt to categorize or even recognise the remarkable hounds used to hunt the boar.

The true boar hound, a hound of the chase or chien courant, as opposed to a huge crossbred dog once used at the killing of the boar, deserves our respect. Such a hound was required to pursue and run down one of the most dangerous quarries in the hunting field. It needed to be a canine athlete, have a good nose, great determination and yet not be too hot-blooded. Both the Fila Brasileiro and the Dogo Argentino have been used in the boar hunt in South America. American Bulldogs are still used as catch-dogs on feral pig in the USA. In our modern so-called more tolerant society, such brave dogs are stigmatized for being what is termed by the police experts as 'persistent' and even banned - for what is actually courage under fire, in military terms. We have surely become a very confused society.

The great forests of central Europe provided endless opportunities for hunting. In the 19th century the pursuit of wild animals with hounds was conducted on a vast scale. In France there were over 350 packs of hounds. In 1890 the Czar of Russia organised a grand fourteen-day hunt in which his party killed 42 European bison, 36 elk and 138 wild boar. The Greeks considered the boar hunt to be the highest manifestation of the chase for the hunter and his hounds. Many of the hounds were killed on each hunt. Xenophon recommended Laconian hounds for the pursuit and Indian hounds at the kill; the boar being despatched with a spear not by the dogs, although at times they would be holding on to the boar when the kill was made. The Laconian or Spartan hound was harrier-size and a superb tracker; the Indian hound was bigger, heavier -- well described as a hunting mastiff. No hunter wants to lose his best scenthounds to the tusks of a wild boar and because of the high risk of canine death, two practices were introduced. One was to protect the hounds with protective clothing like chain-mail. The other was to introduce less valuable, more expendable, huge, cross-bred dogs for the killing stage. Later on, when firearms were invented the hounds were used to bay the boar which was then despatched by a boar-lance or a special knife-like sword or by shooting, rather like modern stag-hunting. Gaston, Count of Foix (1331-91) known as Gaston Phoebus, considered the killing of a charging boar with a sword on horseback as being the finest feat any hunter could achieve.

The ancient Greeks, Gaston Phoebus in the 14th century, the Bavarians in the 17th century and the Czars in the 19th century used hunting dogs of different types in unison according to function. Greyhounds, scenthounds and hunting mastiffs were used together and not hunted separately, unlike our more specialist packs. Boarhounds could therefore be the loose term to describe all hounds on a boar hunt, whatever their function in the chase and kill. Casual researchers can therefore look at a painting of a boar hunt or read accounts of one and jump to all sorts of false conclusions about what boarhounds could look like in past times. The illustrations in Gaston Phoebus's well-known "The Hunting Book" depict scenthounds, sighthounds and hunting mastiffs being used complementarily in the hunting field. In Turbervile's "Booke of Hunting" of 1576, he describes bloudhoundes, greyhoundes, mastiffes and a variety of scenthounds being used in support of each other. But as firearms developed, both in range and power, the role of the killing dog became obsolete. Hounds of the chase and the hunter with the gun could get by without ‘beissers’ or "holding and killing" dogs.

The one-time heavy demand for the 'beissers' (literally ‘biters’, but also known as catch-dogs, gripping dogs or holding dogs) was rooted in the remarkable taste for hunting the bigger quarry in Northern and Central Europe using powerful dogs and hand-held weapons five hundred years ago. It is important to keep in mind the sheer scale of hunting in middle Europe from medieval times up to the late 18th century. Elector John George I of Saxony (1611-1656) held hunts that killed 31,902 wild boar. His son reduced this to 22,298 during his time! The scale too of hunting kennels needs to be remembered. The early 17th century hunting calendar of the Waddesdon Bequest in the British Museum lists in just one: 40 Leidt Hunde or leashed scenthounds, 40 Blut Hunde or trackers, 200 Ruden or pack hounds, 40 Englische Hunde, 30 Sau Finders or boar 'finders' and Leib Hunde, literally 'body dogs' or the dogs that closed with the quarry. The running mastiffs of northern Europe, the Great Dane and the Broholmer, are ruden. Behind these breeds and the Boxer however, there is a breed-type, commonly called Hetzruden or hunting packhounds, frequently including matins or boar-lurchers, and extensively used in boar-hunting in the forests of what is now Germany. These strong-headed, ferocious, heavy hounds were often fortified with the blood of hunting mastiffs from England. Some writers considered these dogs, which were kept in kennels described as 'English stables', possibly because of the size of the dogs, to be a blend of Irish 'greyhound' and Englische Dogge or Mastiff.

Young boarhounds, still learning, or highly valued hounds were equipped with padded jackets of brown fustian (a thick hard-wearing twilled cloth) or of bombazine (a twilled fabric of worsted and silk or cotton), with whalebone on the chest and belly to reduce the ripping action of the enraged boar's tusks. The Duke of Coburg's old sporting armouries near Gotha featured coats of mail, made up of leather or strong canvas, fastened with wire and hempen cord. The old German princes liked to pick out the biggest and best of these brave hounds to serve as bodyguard dogs; these wore silver or silver-gilt collars, lined with velvet and edged with tasselled fringes. Many of these dogs were killed in the chase. Landgrave Philip wrote to Duke Christopher of Wuerdenberg in 1559: "During this boar-hunting we took 1120 wild boars with the help of our home-bred dogs..." This could have led to the death of several hundred dogs, there being an expression of that time that "those that wanted to have boars' heads had to sacrifice dogs' heads."

Duke Henry Julius of Brunswick was reputed to own the largest number of hetzruden: 600, in 1592. Whilst each castle featured its own kennels, the sheer numbers led to forcible boarding out. Shepherds were required to board at least one, in addition to their stock dogs, or their lambs were confiscated. In the 17th century, millers were required to board a specific number each year. Eventually over-hunting led to a vast reduction in boar numbers and a consequent reduction in Hetzruden. In time, only small numbers of them were kept at the princely courts, and, towards the end of the 19th century, they became increasingly the property of private citizens. The last of the Hessian dogs was sold in 1876. They were described as being fawn or red-fawn with black masks and muzzles. In Hutchinson’s Dog Encyclopaedia of 1934 there is reference to the entering of such dogs to their hunting role: “The training of the Hatzrueden consisted of the younger ones, accompanied by older dogs, being put in the presence of wounded wild boars, when they had to seize the latter sideways by the ear; later on the youngsters were put against two-year-old wild boars, but were supplied beforehand with so-called ‘protective jackets’, to protect them against the tusks of the boars.”

As referred to earlier, hounds that hunted boar were often killed in the hunt and boar hunting in Central Europe down the ages was massively conducted. In 802AD Charlemagne hunted wild boar in the Ardennes, aurochs in the Hercynian Forest and later had his trousers and boots torn to pieces by a bison; all three quarry were formidable adversaries and were hunted by the same huge hounds. The sheer scale of hunting is illustrated by these 'bags': in 1656, 44 stags and 250 wild boar were killed on Dresden Heath; in 1730 in Moritzburg, 221 antlered stags and 614 wild boar were killed and in Bebenhausen in 1812, wild boar were pursued by 350 'strong hounds', clad in armour like knights of old. Hunting big game in Western Europe in the Middle Ages was more an obsession than a pastime - so often a demonstration of manliness. Between 1611 and 1680, gamebooks reveal that around 40,000 wild boar, sows and young boars were killed in Saxony. In 1737, King Augustus II himself killed more than 400 wild boar in the course of a single hunt in Saxony. John George II, killed over 22,000 wild boar in 24 years. In the Bialowieza Forest in 1890, in a fortnight's hunting, 42 bison, thirty-six elk and 138 wild boar were killed. This is the frame in

which to picture the Great Dane type as a bison hound, auroch hound, staghound and boarhound. Perhaps because of the wholly arbitrary division of hounds today into scent or sighthounds, multi-purpose hounds which hunted 'at force', using scent and sight to best effect, have been neglected. They deserve recognition and our admiration.