1188

THE FOXHOUND – NOT ALWAYS WELL BRED

By David Hancock

“On the straightest of legs and roundest of feet,

With ribs like a frigate his timbers to meet

With a fashion and fling and a form so complete,

That to see him dance over the flags is a treat.”

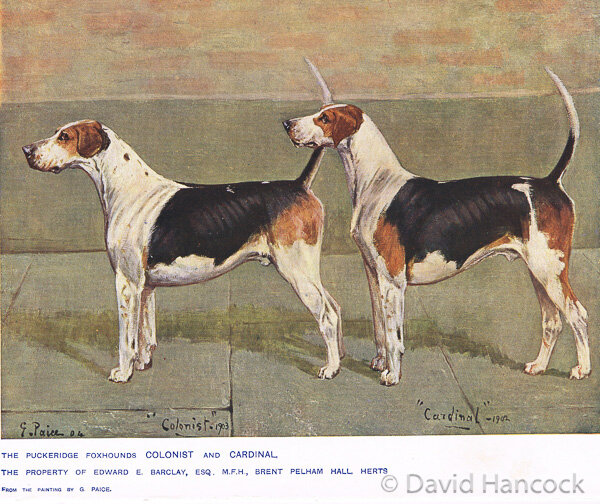

Those words of Whyte Melville tell you a great deal about flawed Foxhound thinking at the start of the 20th century, inflicting wholly unnecessary handicaps on the hounds and their calling. But those years soon saw significant changes in hound-breeding; the importance of an infusion of Welsh Hound and Fell Hound blood into many packs, as well as the value of the Belvoir stallion hounds, was recognized. More importantly, the emphasis on drive, nose, cry and pace led to the development of more athletic lighter less-boney hounds. The main instigator of this was Sir Edward Curre at the Chepstow Hunt. By the end of the Great War he had already had some twenty years of combining the merits of top-quality English bitches with proven Welsh stallion hounds, usually in a white or light jacket. He inspired others like Sir Ian Amory of the Tiverton and Isaac Bell of the South and West Wilts and influenced the Heythrop, Portman, Vale of the White Horse, Puckeridge and Old Berkeley packs. Out went the over-boned, massively-timbered, pigeon-toed hulks and less favoured were the classic tricoloured Belvoir markings. By the 1930s, the ‘Peterborough type’ had been superseded by the lighter-boned, pacier hounds with better stamina. The importance of the ‘female line’ in breeding was recognized, overcoming the slavish adherence to the ‘sire-dominated’ thinking of the previous century.

Writing in his Hounds & Hunting through the Ages of 1937, Joseph B Thomas, himself a distinguished MFH, gave the view that “…a well-made hound standing, say 23 inches, symmetrically put together anatomically, with sufficient bone on which to hang muscle, must have an advantage over a hound of equal height that carries weight of bone more than essential for strength.” An editorial in the prestigious sporting magazine The Foxhound of July 1911 stated: “…by concentrating attention on the qualifications in breeding hounds which produce perfection in conformation we have somewhat overlooked these important factors for success in the hunting field…excessive development in one particular must act detrimentally upon the others.” This was in a discussion about the alleged loss of endurance, nose, tongue and pace in Foxhounds at that time. At that time too, the importance of the ‘female line’ in breeding was finally acknowledged, overcoming the slavish adherence to the ‘sire-dominated’ thinking of the previous century.

Looking back at the foolishness of the 1890-1925 period in Foxhound breeding, there are echoes of the 1960-1990 period in the show world in a number of breeds – some still having harmful advice, like ‘must stand over a lot of ground’, in their Breed Standards. In 1914, Cuthbert Bradley, ‘Whipster’ of the influential ‘The Field’ magazine, wrote a book entitled: The Foxhound of the Twentieth Century’, a 308- page tome, with many illustrations, mostly by him. In his book, which became a sort of handbook for many, he advises some of the worst features of any hunting dog as desirable features. For example: “Although bone in the foxhound below the knee is most desirable, and a valuable asset for a first-rate pack of hounds, yet Mr Henry Chaplin has said, ‘that an excess of bone in a race-horse or a foxhound, may amount to a matter of vulgarity’.” Well said Mr Chaplin! Bradley also wrote: “The modern foxhound has the forearm of a lion, and shows short, solid, good bone from the knee to the toes…The best models today knuckle over very slightly…” Show me a French hound of his time with such features! He also wrote: “Round cat-like feet, and close toes turning inwards, are said to be less susceptible to damage than long, fleshy toes that spread, and the right construction of joint behind the knee ensures against undue concussion on rough or uneven ground.” He seemed to have no idea of how creatures that hunt using pace and stamina are built. He then sketched such flaws as benefits!

(Bradley’s captions gave praise to each one!)

Hound Show Effect

Hound-shows like the prestigious Peterborough event have long had considerable influence in the Foxhound world. But it has had its critics too. In his English Fox Hunting, A History, of 1976, Raymond Carr writes: “Some great breeders have doubted whether the characteristic Edwardian emphasis on appearance and size, fostered by Peterborough, produced the best kind of working hound…One side held that Peterborough shows were improving the standard of hounds all over the country by setting a high standard for every kennel. The other that the mania for Belvoir blood had produced ‘lumbering caricatures of their ancestors’. Peterborough was ‘a place of temptation’; masters took hounds almost entirely to gratify their hobby of breeding for shows…” Today this sort of criticism is aimed at working terrier and lurcher shows too; man’s desire to show off his stock is fine when the wallet, and the ego, are held less important than the soundness of the exhibits.

“As well as shape,

Full well he knows,

To kill their Fox

They must have nose.”

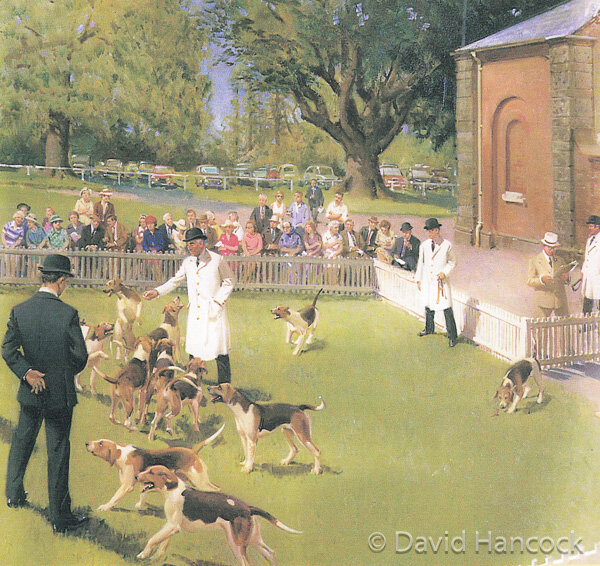

Those few words by ‘NCH’ in M’Neill’s Hound List emphasize very neatly the requirement to breed for performance ahead of any cosmetic appeal. Breeding for performance ahead of appearance and breed-dogma means that the applied breeding criteria are definitive. If the hound doesn’t measure up, it’s not bred from, no matter how pretty it is. It produces healthier sounder hounds since the chase reveals every fault. Racing Greyhounds have succeeded in the show-ring but it is not likely that a show Greyhound would win on the track. The socialization of Foxhounds by puppy-walkers allows hordes of delighted children to descend on them in the arena at country shows. This is an exercise that could not be similarly conducted using a couple of dozen unleashed dogs from quite a number of pedigree breeds. But however admirable their temperament, it’s their anatomy that wins the most praise. In his book Hounds, Long, 1914, sportsman and veterinary surgeon, Frank Townend Barton was writing: “This brings the author to make a statement that very few will, on reflection, feel inclined to dispute the truth of. It is this: That the Foxhound is built upon lines displaying greater economy of material than that of any other variety of dog. Every ounce of bone and muscle is placed where it can be utilised to the best advantage.”

I have written earlier on how, in the second half of the 19th century, the Foxhound fraternity lost its collective head and actually favoured massive leg bone, over-knuckled feet, bunched toes and woefully pin-toed fronts. The redoubtable 'Ikey' Bell and his followers fought hard against such folly and the penalty to a hound of being over-timbered or unsound afoot was eventually conceded. Quite why any lover of hounds would want them to resemble carthorses has never been satisfactorily explained. What is frightening about what Daphne Moore has called the 'shorthorn' era is that so many highly-experienced MFHs and huntsmen went along with the foolishness of the day. Consensual foolishness is still foolishness! A Hound-show like those at Peterborough, Reigate, Harrogate, Ardingly, Rydal, Honiton or Builth Wells should be a joy to visit if you admire fit dogs, dogs in tip-top condition. At a number of recent Hound-shows I have been disappointed to see some of the long acknowledged scenthound flaws creeping back in: fleshy feet, bunched toes, toeing-in, over-boning at the knee and forelegs arrow-straight when viewed from the side, allowing no 'give' in the pasterns. Flaws can still occur even in working hounds.

But if any breed of dog should be chosen to epitomise the English sporting dog then the Foxhound has to be at the top. The Bulldog may serve to exemplify British stoicism, the Bull Terrier to illustrate sheer tenacity and perhaps the Jack Russell to typify English eccentricity. But the Foxhound, for breeding excellence, field performance and sporting aura, some might say handsomeness too, is way out in front as the sporting dog. It may be questionable to regard the Foxhound as a breed, with some packs having claims to a distinct type or variety under that name, as the Dumfriesshire pack long demonstrated. But the Kennel Club recognises the Foxhound as one breed, with one breed standard, and, as with every breed registered with them, will seek standardisation and conformation to a set word picture. KC recognition will hardly be noticed in the Foxhound packs of Britain and foxhunting itself is fiercely debated by those styling themselves as animal welfarists and the class-warriors. In a democracy, challenges like these are to be expected. But no-one with knowledge of dogs, sporting dogs especially, would challenge the view that Foxhounds are just about the best-bred of the canine species in Britain. Their uniform quality, across the packs, has been matched in my experience only once, when I studied the Finnish Hounds at the World Dog Show in Helsinki some years ago now.

Hounds used on fox, like the Welsh, with its rough-haired ‘griffon’ coat, the Fell, with its lighter frame, those indicating the Curre influence at Chepstow - with that characteristic lighter coat, and the Dumfriesshire, with its distinctive black and tan jacket (but now sadly lost to us as a pack) and say the Belvoir with its classic, tan-based, tri-colour markings, don’t exactly fit in with one firmly-worded blueprint. Although the KC standard for their breed does allow any recognised hound colour and markings, I doubt however whether they would be happy with merle, as found in the Dunker Hound of Norway, harlequin as found in the Russian Hounds or the red-tick and blue-tick coat colourations found in US hound breeds. All these breeds are recognised by overseas kennel clubs. Foxhound experts like Beckford, Osbaldeston, Paget, Bell, Higginson, Wallace and Rycroft have long expressed clear views on the coat colour and the conformation of the Foxhound.

Beckford gave the view that ‘the colour I think of little moment’; Fox, for over 40 years a huntsman and whipper-in, wrote in 1924, under his pseudonym ‘Yoi-over’, of: “…our native foxhounds…rich and varied colours, tan – deep and light – black and tan, and the white flicked and bitten; one was white and spotted like a Dalmatian carriage dog.” Rycroft has questioned whether the tan eyebrows on a black and tan hound indicate a throw-back to the ancient St Hubert hound, going on to state that blue-mottle is often linked to a good nose. In his masterly Hounds of the World of 1937, Sir John Buchanan-Jardine, wrote: “In the colour of foxhounds there are again different tastes. At one time, Belvoir tan hounds were the only ones in the fashion, and the less white they had on them the better coloured they were considered to be. Now there is a fashion among some Masters for very light-coloured hounds, sometimes almost white…I have known many good hounds marked with blue-mottled colour, and with tan ticks down their legs, perhaps throwing-back to the old Southern hound blood. Again, I have known many very good hounds with a lot of black about them, particularly about the head…it is really a great mistake to allow oneself to be prejudiced by mere colour when breeding hounds…” That judgement could be valuably extended to read when breeding dogs more generally.

As a result of better-informed breeding plans, based on knowledge gained from hunting rather than ‘so-called authorities’, the breeding of Foxhounds now should act as a model for dog-breeders everywhere. The whole aim is to produce a better-performing hound, with cosmetic points never to the fore. The mania for pure-breeding has rarely afflicted sportsmen, hound breeders especially. Ronnie Wallace used outcrosses which were American, West Country Harrier, Fell and Old English, but not Welsh, as is often the case in the pursuit of improved scenting and voice in some English packs. Quite a number of British packs have made use of mottle-coated Gascon hounds, with the French often resorting to Anglo-French blends, especially in the late 19th century.

Breeding for performance ahead of appearance and breed-dogma means that the applied breeding criteria are definitive. If the hound doesn’t measure up, it’s not bred from, no matter how pretty it is. It produces healthier sounder hounds since the chase reveals every fault. Racing Greyhounds have succeeded in the show-ring but it is not likely that a show Greyhound would win on the track. The socialization of Fox hounds by puppy-walkers allows hordes of delighted children to descend on them in the arena at country shows. This is an exercise that could not be similarly conducted using a couple of dozen unleashed dogs from quite a number of pedigree breeds. But however admirable their temperament, it’s their anatomy which wins the most praise. In his book Hounds of 1914, sportsman and veterinary surgeon, Frank Townend Barton was writing: “This brings the author to make a statement that very few will, on reflection, feel inclined to dispute the truth of. It is this: That the Foxhound is built upon lines displaying greater economy of material than that of any other variety of dog. Every ounce of bone and muscle is placed where it can be utilised to the best advantage.”

It is this impressive physical stature, allied with great staying power and backed by nose and voice, which has seen the breed exported all over the world, to improve their local hunting dogs, from Sweden and Finland in the north, across the channel to France, and even further afield to America, Australia, South Africa and India. There may well be more paintings of them and books on them than any other breed of dog, such is the long-standing admiration of their prowess. This level of excellence has not come about by accident. In his book The Foxhound of the Future of 1963, CR Acton wrote: “Though the science of genetics, itself, is new, the principles of heredity were in operation before Mendel’s time. For years the breeding of fox-hounds by selection was based upon success, and the elimination of such methods as were unsuccessful. Such success was achieved by methods that were, unbeknown to the exponents, to a certain extent in accordance with the principles upon which the science of genetics is based. Hugo Meynell, Lord Henry Bentinck, Lord Willoughby de Broke, Lord Fitzhardinge were applied biologists, whether they realized the fact or not.”

It is to such men that we owe the Foxhound of today, and, whatever its restricted use, it stands as a tribute to British livestock breeding down several centuries. In the first volume of The Foxhound Studbook, published in 1866, by Cornelius Tongue, it was stated that “the successful breeder of hounds should follow the principles of the successful breeder of race-horses, as it is invariably found that those animals are most to be depended upon for the perpetuation of their species whose genealogy can be traced in the greatest number of direct lines to great celebrities of olden times.” In other words, study the pedigrees! And, whether the Foxhound graces the conformation show scene or parades at Honiton and Peterborough, the breeding behind the hound will come through, backed by informed selection and as always, cheered on by a host of admirers. The Foxhound reigns supreme, as the physically-soundest, as the most eye-catching and, most important of all, as the canine athlete.

“What other breed of dog is there that could trot out a dozen or fourteen miles along the roads to a meet, then gallop about for five hours or so, often hard enough to tire out two thorough-bred horses in succession, all the time using his nose, intelligence and voice, then come home at night with his stern up, and do it regularly twice a week?…it is a great deal to expect of a dog.”

Sir John Buchanan-Jardine MFH, in his Hounds of the World of 1937.