1195

DOG’S COLOURING BOOK

By David Hancock

The fashion magazines sometimes show us pictures of wealthy dog-owners who have dyed their dog’s coat to match the colour of their latest outfit – yet another example of the human tendency to regard dogs as playthings rather than sentient creatures with needs of their own. I just wish such people would wear flesh-coloured clothing and match it with a roast-bone for their dog! Across the pedigree dog spectrum there is a huge range of coat-colours, some chosen as a preference rather than a hallmark of the breed. So often in breeds of dog the colour of the dog’s coat is the appeal, before temperament, longevity or the presence of genetic defects in that breed – ahead of any other considerations. Would not people who choose Dalmatians, harlequin Great Danes, red Irish Setters, pure white Samoyeds, a rich golden-liver Sussex Spaniel or a sedge-coloured Chesapeake Bay Retriever quite often have the coat-colour as their leading criterion in choosing one of those breeds? Conversely, there is a lack of desire in far too many breeders for a coat-colour that do not match their personal need. A wide range of coat colours in a breed is a strength; breeding to a single, or for an isolated, colour is not always good for a breed.

A century ago, the writer and vet Frank Townend Barton was horrified to discover a white pup in his newly-arrived litter of otherwise black and tan, purebred Bloodhounds. The unfortunate pup was quickly consigned to the bucket, an act he later said he regretted. In recent years, mainly white Mastiff pups have been born both in America and Australia, from entirely different lines, only to be quickly sterilised. A piebald Bullmastiff was also born in America, leading to murmurs of a misalliance, despite the past existence of white Mastiffs and Bulldogs behind the breed, as historic depictions demonstrate.. Genes work in a random not a mathematical way. Half a century ago, a yellow Labrador bitch was mated to a brindle Bullmastiff dog, producing ten male pups, which closely resembled black and tan Rottweilers. Not even knowledgeable dog-men would have predicted that! Interestingly, two of these lived to be 19; if only Bullmastiffs could live that long.

A Newfoundland can be chocolate or bronze; a Labrador can officially only be chocolate and not bronze but I see bronze Labradors from time to time. The Labrador's coat too has to be 'without wave' but I see distinct waviness in many working Labs' coats. Merle is unwanted by some in their breed, like the Great Dane, but tolerable in Border Collies. Breeding merle dogs is not a task for those lacking knowledge of its perils. But, in many lurchers, the blend of ingredients assures healthy dogs with very attractive coats. One lurcher breeder specialises in red merle dogs from collie and Kelpie stock. Another, the most prolific lurcher breeder in Britain, produces top quality hunting dogs in black merle. Used soundly, and not for dogma, coat-colour preference can be justified. But when such a preference threatens the genetic health of a breed or narrows an already restricted even further, warning lights should be flashing!

No Rhodesian Ridgeback breeder wants a brindle but a brindle ridgeback-lurcher can be a most handsome and virile dog. Cross-bred dogs can be extremely hardy and live long healthy lives. Great Danes are favoured in brindle, fawn, black, blue and harlequin; white is not desired, with mainly white dogs quickly going to the pet market. When a ‘freak’ colour crops up in a litter, there are instant cries of a rogue male ‘getting in’ unnoticed, but no real notice is taken when a black and tan pup crops up in a purebred Labrador litter, parented by pedigree dogs, with no outside interference at all. This is genetic diversity not being taken advantage of – out of pedigree dogma, not heath interests. I understand that the use of Briard blood in lurcher breeding guarantees black and tan pups. I see impressive hybrids at nearly every country show I attend, bred mostly to a plan and not by accident.

But fashion too plays a big part in colour selection. The Duke of Gordon favoured tricolour setters; the breed named after him now features black and tan dogs with only a 'very small white spot on chest permissible'. The Breed Standard then adds menacingly 'No other colour permissible'. The best working Gordon Setter for some years, FTCh Freebirch Vincent, was a mainly white dog. The most famous setter-man Edward Laverack once wrote: "...mere beauty of colour and perfection of external form...are but secondary considerations...and simply valueless...select a bitch with a strong, robust, healthy constitution, regardless of colour..." It is strange how breed fanciers can revere great pioneers in their breed - and then totally ignore their advice! I haven't seen a solid-white English Setter for some years, they are invariably flecked or splashed with a darker colour over white.

Gundog men have varying views on coat colour. Black and tan Pointers are hard to find but were once a feature in partridge shooting, as the paintings of Alken and Bentley illustrate. It would be nice too to see an all-black Pointer once again; the Duke of Kingston's in this hue were much admired. In France, in Edwardian times, black Pointers were favoured there whilst being overlooked here. In the standard of the Cocker Spaniel the colour of the coat is described as 'various' but until recently I had never seen a sable, a very handsome hue. The Weimaraner and the Irish red and white Setter are set apart by their coat colour but the Brittany, unlike the similar Welsh Springer Spaniel, can have a much wider range of coat colours. The Italian gundogs, the Spinone and the Bracco have a range of roan shades, but still look distinctive. The Vizsla has one colour but there is still some variety in that colour. Golden Retrievers however now have so many shades of ‘golden’ that the breed title could be challenged.

The terrier men too have individual views on the coat colour of their dogs, although this is more in the show-ring than the field. Black Bedlington Terriers are not wanted in the show ring but do feature at country shows. The sandy coat is less favoured than the blue yet is an attractive shade. Brindle in the Staffordshire Bull Terrier can be any shade, but the darker brindle is much more prevalent. Re-creations of the old English White Terrier often have a black or tan spot to deny albino-genes any room. White Lakelands can be found at working terrier shows and black Airedales are favoured by a few breeders in the USA. Plummer Terriers have to feature a rich fiery red-tan coat but the Fell terrier comes in a number of solid colours. As always, the colour of a dog's coat varies as much as human choice decrees, but it cannot be right to rule out colours that can manifest themselves from the breed's gene pool. An outstanding dog is outstanding whatever the colour of its coat. A failure to breed from an outstanding dog because it features an unwanted coat colour tells you a great deal about human foolishness. Today’s pedigree breeds need all the genetic diversity that they can muster; a rigid adherence to a narrower range of colours than is actually available is to further reduce a gene pool, sometimes dangerously.

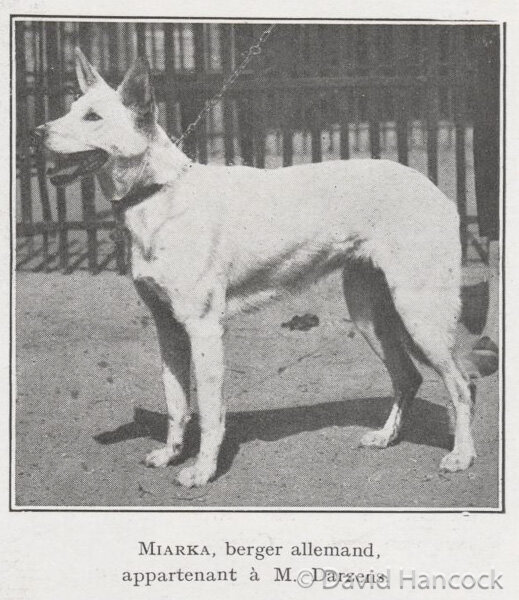

In the German Shepherd Dog, whites or near whites are listed as 'highly undesirable'; but the standard goes on to inform us, in direct contradiction of this, that 'colour in itself is of secondary importance having no effect on character or fitness for work.' I find the whites and creams the most appealing, the solid blacks the most impressive. It is interesting to note that in 1905, Richard Strebel was depicting harlequin/merle specimens in this breed. I can understand the exercise of human preference in coat colours by individuals but find it difficult to comprehend the virtual banning of colours available from the breed's gene pool. Narrowing down selection in a closed gene pool makes little sense and isn't in the best interests of the breed - which fanciers claim to foster. The merle colour is not rare in pastoral breeds but has been bred away from in so many of them. The German Breed Standard for their shepherd dog of 1930 mentions under colour: white mixed with dark patches (blue, red, roan, etc.), mostly dark-cloudy (black tinge on grey, yellow, red-yellow, or light-brown ground with the corresponding light markings). White GSDs were once favoured by farmers in Northern Germany; the Pomeranian Sheepdog was all-white. French farmers have no problems with their impressive herder, the Beauceron, which can feature grey and black patches. With this range of colours in its gene pool, the GSD could rival their Belgian and Dutch equivalents and form several varieties or even breeds of that name.

The American herding dog, called appealingly the Catahoula Leopard Dog, can be red merle or black merle and is a striking-looking breed (as indeed too is the well-named Black-mouthed Cur). Can farmers in one country have comparable colour prejudices to farmers in another, but favour wholly different colours, on rational criteria? Leading geneticist and GSD expert, the late Dr Malcolm Willis, has written: "Colour is of a certain aesthetic and economic value but it has no bearing upon the physical and mental ability of the animal: hence attention to colour, whilst it is necessary, should not become an all-important factor in matings, and the avoidance of a potentially great stud dog on colour grounds is generally unwise." Sadly, if a piebald Mastiff were to survive puppyhood and turn out to be the best specimen that anyone could ever recall, it is unthinkable for it to feature in breeding programmes. Colour prejudice rules! But when Danish geneticist Ojvind Winge examined the records of the kennel club registrations of that country, nearly a century ago, he was disappointed to discover that a significant percentage of dogs registered, could not have been born from the parents listed, on colour-inheritance grounds. Coat-colour never lies!

A complication in recording coat-colours results from the loose use of colour descriptions. In his 'Genetics for Dog Breeders' (Pergamon Press, 1989), Roy Robinson writes: "Different people may use the same term for dissimilar colours or different terms for the same colour. Three common errors are the misinterpretation of liver as red, the confusion of saddle pattern with black and tan, and confusion of saddle pattern as sable or vice versa...In the case of black and tan, the confusion has even reached into the wording of standards, where a reference to black and tan may actually mean saddle pattern." The KC defines sable but admits that its definition varies with the breed. Is that helpful? The KC defines saddle but states that it can be 'a variation in colour over the dog's back, as in the GSD, or an area of shorter coat over a dog's back, as in the Afghan Hound.' In other words, it can be a matter of coat-colour or colour-location. What help is that?

What is the difference between red, liver, dark liver, red-wheaten, red-tan, red-fawn, red-brown, reddish fawn, reddish-brown, red gold, chestnut-red, rich red, rust red, rich tan, deep red, red sand, clear red, deer red, orange, russet gold, russet, rich chestnut, orange-red, sedge, mahogany, mahogany-tan and bright tan? Each one appears in a Breed Standard. What is the difference between a deer-red Bullmastiff's coat-colouring and the intense-red of the Japanese Shiba Inu? Imagine the dilemma facing a novice-breeder, attempting to register a litter containing rufous pups for a breed which permits all colours!’ The Whippet, Akita, Pomeranian, Pekingese, Lowchen, Havanese and Chihuahua standards do not specify colours, for example. Should not each breed have its own precise use of colour descriptive words exclusively?

In past years I have been involved in drawing up Breed Standards for working springers and Labs in the gundog world, for the Plummer, Sporting Lucas and English White in the terrier world and the Victorian and Dorset Bulldogs. In each one, and that of the Sporting Lucas, has now been recognised by the United Kennel Club of America, care was taken to use words on colour very carefully. In the Plummer Terrier for instance, the red coat is described as fiery red; no other breed uses that description, fiery red belongs to that breed. A similar approach could be made to every breed, but it really needs registry-coordination. It leads to confusion if each breed club or council is allowed the last say over the wording of the colour description in Breed Standards. Does it matter? If you are seeking an individual identity for each breed, then yes, it does matter. Descriptions of breeds, desired to be solid white, are wise if they allow a small black or tan marking somewhere, to guard against albinos being born.

Coat colour is often linked by some fanciers to performance. In coursing Greyhounds, for example, blacks have been shown to be successful. In 1830, an analysis was carried out showing that black or mainly black dogs won 617 prizes in one year, against 318 by other colours. Stars of the coursing field were all-black dogs like Master M’Grath, Snowball and Brigadier. The Egyptians favoured red hunting dogs. The Greeks prized brindles, especially in big game hunting. The French had their renowned white scenthounds and the Italians like their roan gundogs. Many extremely clever hunting dogs are red, from the perky Finnish Spitz to the handsome Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever. The black and tan pack, now dissolved, the Dumfriesshire Foxhounds, was renowned throughout the world of hunting, as is the Scarteen, in this livery. West Country Harriers are preferred in the lighter scenthound colours.

A whole raft of telling questions come to mind when ruminating on the dog’s colouring book. When did you last see a black Samoyed? How often do you see a wheaten Scottish Terrier? Have you ever seen a dappled Dachshund, strangely unfavoured in the modern era. When did you last see a brindle Bull Terrier? There are plenty of Staffordshire Bull Terrier whole-brindles and in a coloured Bull Terrier brindle is actually preferred in its breed bible. Have you ever seen a slate-grey Irish Terrier? I used to see them when working in Ireland. Is the Golden Retriever actually not just another variety of Flat-coated Retriever - the retriever family can embrace black, ‘yellow’ and chocolate coats – as the Labrador exemplifies. But is the Yellow Lab losing its true coat-colour? I see them ranging from a pale tan to a faint fawn, especially amongst the working strains. But how many pure white Pomeranians have you seen in today’s show rings? If they were bred down from the old white Pomeranian Sheepdogs originally, then we have lost some strong genes. We are losing diversity in this field when this is very much a buzz-word today.

To favour a coat colour is just human nature; to discriminate against a perfectly good dog on colour grounds alone has consigned many an undeserving whelp to oblivion. To further limit a closed gene pool by barring a natural colour can only harm a breed. To rely on a breeder's personal colour perception, as well as his familiarity with words which define colour, when a litter is registered, undermines the system, and denies genetic researchers potentially valuable statistics. To obfuscate a breed's identity through imprecise or misapplied colour descriptions does nothing to establish breed identity or perpetuate breed integrity. The words used to describe the colour of the coat in each breed's standard needs attention from the KC. If each purebred breed is to be unique then the words used to identify it have to be uniquely applied. This should not involve colourful language, just accurate words.