1198

OWNING A PURE-BRED LIABILITY

By David Hancock

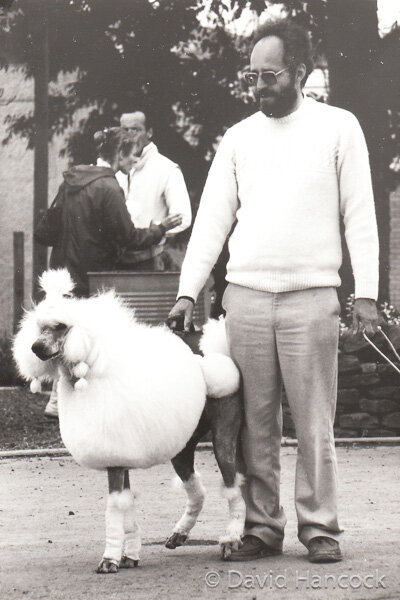

In The Times newspaper of the 23rd of February 2019, the always-interesting, perceptive writer, for several different publications, Deborah Ross, produced a piece headlined ‘Savaged by the pure-breed attack dogs on two legs.’ Her editor had sub-headlined her piece ‘Snobs sneer at my labradoodle as a ‘designer dog’ but how do you think we got from a snarling wolf to a chihuahua?’ In an enlightened piece Deborah Ross highlighted a number of points including paragraphs centering on such topics as ‘British bulldogs are so inbred they are no longer fit for purpose’ and ‘That annual carnival of perverted eugenics they like to call Crufts’. These words may sound sensational but her supporting words fully justified such hard-hitting sub-headlines. The proud owner herself of a Poodle-Labrador cross, known to many as a labradoodle, Deborah Ross had unwisely declared her dog’s breeding to the uppity owner of a purebred Poodle, commenting ‘These designer dogs do seem to invoke snobbery at best, and actual full-on hate at worst. Mostly the hate comes from what we will call ‘the pure breed fascists’ (PBFs) as that is what they are.’ She went on to point out that all dogs are designer dogs since you can only have a human-engineered breed, illustrating these words with the examples of the Airedale Terrier and the Golden Retriever, describing their mixed origins for a recognized purpose, although not as companion dogs.

If pure-bred means of unmixed descent then it can hardly be applied to our recognised breeds of dog, those registered as breeds by the Kennel Club. According to the KC's own Glossary of Terms, the words pure bred are defined as 'A dog whose sire and dam belong to the same breed and are themselves of unmixed descent.' If the caveat 'for a minimum of five generations' had been added to this definition, it would have had greater validity. I would be interested to know of a recognised breed that is truly of unmixed descent. Such an event is as assailable as the statement that modern dog is descended from modern wolf, as so many unscientifically claim. But for a breed to come from mixed ancestry is for me a strength not a derogatory, sly gibe. It is fair to state, I believe, that only show breeders rate purity of breeding ahead of the worthiness of the individual dog. To value a dog solely because it is a registered pure-bred dog and not mainly because of its mental and physical attributes is, to me, irrational and unwise. Deborah Ross’s words, and her argument, are fully justified.

Those who use dogs, sportsmen, hunters, shepherds and ranchers, demand dogs with ability. The hunting world both here and overseas has long sought field excellence ahead of any cosmetic value or respect for registries. The maintenance of a studbook has for them been important eugenistically not the dogmatic insistence on a closed gene-pool, come what may. Writing in Hounds magazine in 2004, Charles Fielding, an acknowledged expert on hound breeding, used these words: "Fortunately hounds are bred from in the winter when their working abilities are foremost in the mind, but woe betide anyone who tries to breed for looks alone." It is hard to imagine any breed registered with the KC following such a philosophy. Breed purity and cosmetic appeal has in so many breeds held sway over soundness, health, historic type and ability to fulfil the breed's original purpose. That is precisely why the purebred dogs of today have lost virility and any natural disease-resistance.

It is strange that outcrossing to another breed either to restore type or improve the phenotype is considered an anathema by so many pure-bred dog devotees. The list of breeds improved or developed by such an outcross is already impressive: Foxhound blood in the Pointer, Greyhound blood in the Deerhound, Springer blood in the Field Spaniel, Tibetan Mastiff blood in the re-created Irish Wolfhound and the use by Millais of Bloodhound blood in his Basset Hound breeding plans, for example. Inspired breeders used selected breeds for the blend which produced the Dobermann, the Korthals Griffon, the Black Russian Terrier and the Dogo Argentino. The surreptitious use of Borzoi blood to change the shape of the Collie's head, of Wire-haired Fox Terrier blood in the Welsh Terrier and of Pug blood to change the jaw length of the Bulldog is rarely aired. The Mastiff was re-created here in the 19th century using the blood of the Tibetan Mastiff, the Great Dane and the Alpine Mastiff, but is still usually described as our 'ancient breed'.

Despite that background the fierce defence of pure-breeding is the norm in Britain, but not in the hunting field, where performance is all and the conformation to achieve that performance studied assiduously. The blood of the West Country Harrier can be found in most Foxhound pedigrees here and in over forty packs in America. The blood of the Welsh Hound similarly appears in the extended pedigrees in so many packs here. The pursuit of excellence and the desire to improve field performance takes precedence over mere dogma it seems. The French hunting packs soon swooped to obtain the blood of the world-famous Dumfriesshire Foxhounds, when the hunting ban imposed by the Scottish parliament took effect. The Foxhound is recognised by the KC and now appears at KC-licensed shows. I cannot see the blood of Welsh Hounds or Harriers being used to improve the breed's show ring specimens if needed, whatever the hunting mens' views. This blending of blood is how all sporting breeds were shaped and handed down to us; is breeding wisdom going to the dogs!

In spite of the craving for pure unsullied blood, invented breeds like the Kromfohrlander, the Chinook, the Eurasier and the Kyi-Leo, the first-named from an accidental mating between two breeds kenneled together, are now recognised as breeds abroad (and the Eurasier here). Where is the logic in such recognition? It makes the insistence on closed gene-pools look absurd. Of course, crossing two breeds needlessly doesn't make sense, if necessary when the production of say a purpose-built lurcher is desired. But when cross-breeding improves a breed it should surely be welcomed; injudicious cross-breeding however without skilled advice and shrewdly-selected material should always be avoided. There are no magic answers in breeding, the selection of breeding stock based on diligent research is always the way forward.

But the choice of breeding material should be based surely on need, not dogma. In recent years I have seen two 'Mastiffs' which conformed to the type depicted in so many 17th, 18th and early 19th century portrayals. One was a Mastiff-Staffie cross and the other a Mastiff-Bullmastiff cross. The Mastiff of the show ring is for me a fawn Alpine Mastiff, lacking the anatomy of our famous native breed. That may not be surprising, bearing in mind the blend of breeds behind the Mastiff's re-shaping in the 19th century, but is it historically correct? Once, at an Irish Wolfhound ring, I watched a shaggy exhibit for a while and then remembered where I had seen that 'look' previously - in the depiction of an early importation of a Tibetan Mastiff. Capt Graham, re-creator of the Irish Wolfhound used a Tibetan Mastiff sire 'Wolf' on the wolfhound 'Tara' and their offspring appear in the pedigree of every modern Irish Wolfhound.

It is always a risk when crossing two breeds or introducing outside blood into a breed that too much of one feature will crop up in time to the detriment of true breed type. A closed breed gene-pool is unlikely to provide redress. Only once have I detected this 'Tibetan Mastiff look' in an Irish Wolfhound, but I see the 'Alpine Mastiff look' in every contemporary Mastiff ring I view. The Mastiff of England was a hunting dog, a hound; the Alpine Mastiff was a mountain dog, requiring bulk and less athleticism. The mountain dog anatomy is now dominant and, in my view, true type has been lost in this famous native breed. But the breed fanciers seem happy with their stock, which is disappointing. The Mastiff is a feature of our canine heritage and should not be represented by an alien form. If this breed has been 're-created' once and that action condoned, why can't it be done again and with greater historical accuracy this time?

Pure-breeding is worth supporting when it is successful but no gene-pool should be sealed for ever. One faction in the Plummer Terrier world wants to backcross to the Bull Terrier to 'body-up' their dogs. When I judged the breed, I found sufficient stock in front of me, to want to question the wisdom of this proposed outcross. The entry I saw had the breeding material to continue the breed without the alteration to type such a backcross would bring, quite apart from temperament differences. But when judging the Sporting Lucas Terrier at their annual show, I felt it was a pity that there was not one solid red jacket on view. I therefore support the breed committee's decision to introduce Norfolk Terrier blood to restore this breed feature. That, to me, is a sensible solution and a rejection of dogma, for the sake of the future of this appealing little breed. Two different cases and two different solutions.

I have also judged the annual show of the Victorian Bulldog Society and a couple of American Bulldog shows. At each of these shows there were some really sound animals, with no exaggeration. The Bulldogs resembled the dogs depicted in prints and paintings produced in past centuries, not the version of the breed exhibited in th show ring here. There is an abundance of breeding material for any enthusiast wishing to re-create the pre-show ring Bulldog. But of course when I speak to pedigree dog breeders about the sheer quality of these Victorian Bulldogs, I am met with comments such as 'but they're not the real thing, are they'. I think they are; a breed which doesn't resemble its own ancestors, like the show ring Bulldog, can hardly claim to be 'the real thing'. A slavish adherence to a closed gene-pool when the genes are producing either untypical or unhealthy pups is not admirable; it contributes little to the desire we all surely share, that of improving dogs. Perhaps the Kennel Club's self-imposed mandate of 'improving dogs' should be updated to read 'improving the soundness of dogs'.

In his 'Dog Breeding' of 1994 (Crowood), Frank Jackson writes: "The vigour of recently recognised breeds provides evidence of the value of the wise use of cross-breeding." He points out that these crosses make it easier for the breeds to retain genetic health after they have been recognised, as recognition immediately puts a severe restriction on the size of the breeding base. One advantage of the recent blending of Parson Russell Terriers with Jack Russell Terriers is that the breeding population in the combined breed gives far greater flexibility in developing future breeding lines. The white working Lakeland Terrier, as Frank Jackson reminds us, did much to infuse new blood, and a better anatomy, to the emergent Jack Russell. This use of outside blood to improve the breed is not possible now that KC recognition has been obtained. This may suit a registry but does not make for the best practice in the breeding of sound dogs.

In their classic 'Genetics and the Social Behavior of the Dog' (Univ of Chicago Press, 1965), Scott and Fuller report: "...breed intercrosses might be used to produce superior working animals...it should be realised that a breed is a population of individuals showing a limited but still important degree of genetic variability. If selection is confined to one narrowly defined type, the result will almost inevitably be the accidental selection of various undesirable characteristics." They went on to state that breed standards should also cover health, behaviour, vigour, and fertility, as well as stipulating body form. They suggested that obedience and field trials were a valuable step in influencing the selection of breeding stock. My reservation about that would be based on a worry that the dogs which excel at responding to human instructions are not always those able to think for themselves.

It would be a huge step forward however if breed organisations, i.e. clubs, societies and associations, formed to look after individual breeds, came up with proposals for expanded breed standards, as Scott and Fuller proposed. If enough breed clubs responded to such a call, and the work of Scott and Fuller is internationally admired, then national registries such as our Kennel Club might well be supportive. In special circumstances, such as the recent infusion of Bull Terrier blood into the Miniature Bull Terrier, the KC has been both flexible and understanding. When a closed gene pool protects, benefits and allows improvement in a breed, no action needs to be taken. But when a breed loses virility, has a problem with an inheritable defect or is losing true type to an alarming degree, then outside blood has a role to play.

In all areas of livestock breeding the value of hybrid vigour is acknowledged, except in dogs. Some of the most impressive dogs I have seen in the last twenty years have been cross-bred dogs. These have mainly been working terriers and lurchers, but include too: a Springer-Clumber cross, a Dalmatian-Weimaraner cross, a Dogue de Bordeaux-Bulldog cross, a Dobermann-Azawakh cross, a Mastiff-Bullmastiff cross and a blend of Dobermann and Irish Setter. Some were accidental, some were planned with care and knowledge. Crosses between two retriever breeds have been favoured by the Guide Dogs for the Blind organisation. Our ancestors didn't worship the pedigree; sportsmen have kept faith with their predecessors in any number of countries. The best breeders know that you get the best results when you breed one outstanding dog to another, suitably matched. Breeders of packhounds and lurchers still rely on this ancient system. Deborah Ross’s released anger is totally justified, every single breed of dog has been ‘designed’ by man to meet a need; but perhaps breeding to perpetuate an identified function produces a sounder, healthier product, as primitive man soon realized! And, now, as Deborah Ross, rightly points out, her hybrid companion dog is totally ‘fit for purpose’.