1201

‘TYPE’ – A SIGN OF SOUNDNESS

By David Hancock

Those who work their sporting dogs in the field know all about the type of dog that performs its sporting function for them, although increasingly gundog users seem to care much less about it. The Kennel Club, responsible for our breeds of dog, define type as ‘Characteristic qualities distinguishing a breed.’ I’m not so sure that that definition has been sufficient, over one and a half centuries, to protect breed type – certainly not if you look at depictions of breeds in early photographs and compare their appearance with the dogs in those breeds today. There is no such thing as type in lurchers – they have to be able to hunt or they don’t get bred from! Their ability to function determines their appearance and their nature. Terrier breeds have not been so fortunate; the working strains however have hardly changed down the centuries, their anatomy and their spirit simply ensuring their perpetuation. Show terriers and show gundogs have lost their working design and now are nearly always ornamental dogs. That may be the result of such breeds becoming companion dogs and never used for what they were originally designed to do, but I would argue that the original functional type is much more likely to instil soundness, both physically and mentally. The bird-dog breeds in Edwardian times were certainly essentially different from todays’ dogs if photographs of them then are fair examples.

I once had a long but valuable exchange of views about 'type' with a Foxhound enthusiast and hound-show judge. For him, whilst conceding that he liked a Harrier, to look like a Harrier, a Beagle to look like just that and an Otterhound to have its own identity, the role of each hound breed, together with the country hunted over, would always be the decider, not the breed title. For him, 'type' meant the conformation that brought success in hunting a particular quarry. I teased him about the differences between the Welsh Foxhound, the American Foxhound and the Fell Hound - all fox-hunters; he responded quite sensibly by stating their country, i.e. the ground they hunted over, was different so they were too - and he had a point, the Welsh Hound needing a thicker coat, the Fell Hound needing longer legs. ‘Type' in such hounds was based however on a purpose - their function. The hounds of the chase all developed because of what man required them to do! The French hound breeds demonstrate this very aptly, with discernible differences between the country hunted over, ranging from that of Gascony to that of the Vendeen region. But there was always little difference between those hounds in outline or profile; they were unmistakably scenthounds. Their recognition as breeds was based on a pack rather than a 'bred-for' breed.

William Somervile, writing in 1742, gave a hint about the sheer variety available even then in the dog world: "The Chase I sing, Hounds, and their various Breed... And no less various Use..." But what makes a breed of dog a breed? Is it 'type' alone? The domestic dog produces breeds ranging in size from the giant Irish Wolfhound to the tiny English Toy Terrier, in coat from the heavily-coated Bergamasco to the non-coated Mexican Hairless Dog and in shape from the leggy Sloughi to the nearly legless Skye Terrier. Such variations were originally initiated by function: the sighthounds needing the anatomy which allowed them to catch their prey using their speed; the scenthounds needing to have the physique to catch their quarry through stamina; the terrier breeds needing to be capable of entering underground burrows and the gundogs needing the physical qualities to hunt up game or retrieve shot game in all ground conditions. Their working role dictated their physique.

Not surprisingly therefore there are similarities between breeds within each of these groups. The Saluki, the Greyhound and the Magyar Agar have immediately recognisable similarities; the Foxhound, the Finnish Hound and the Hamiltonstovare look very much like each other; a liver and white Field Spaniel is easily confused with an English Springer and ear carriage is the principal physical difference between a Norwich and a Norfolk Terrier. The two breeds of Welsh Corgi are now, post tail-docking, very easily confused. How can you tell a Japanese Kishu from a Balinese Mountain Dog? Do the shepherd dogs of Holland, Belgium and Germany essentially have no other fundamental differences than coat-texture? Is the Japanese Spitz actually a 'reduced' Samoyed from further north? What does make a breed a breed? Does breed-type have value? Or is it just a show-ring nicety?

Whilst the sighthound breeds have a common silhouette, the differences in their hunting styles, hunting country and the local climate have produced small but key differences, such as ear-shape, between the various breeds in the group. All need the long loin to provide flexibility in the fast gallop, a deep chest to enable lung power and immense propulsion from the rear. Sighthounds need length in the forearm to facilitate the fast double-suspension gallop. The Ibizan Hound has a different front from most of the sighthounds, designed to allow greater jumping agility. It displays a noticeable ‘hover’ in its gait. The Whippet has more tuck-up and loin-arch than the Mediterranean breeds. The Greyhound, from the side view, shows the anatomy its users have learned provides speed in the gallop. The shoulder blade is not as well laid-back as in say the ‘endurance’ breeds, like the sled-dogs, and the upper arm is more open than in a non-sporting breed, with a proportionately longer fore arm. The Greyhound’s front pasterns are long and sloping due to the immense ‘bend’ needed there at great pace. Many Saluki owners prefer the smaller, more energy-efficient type, since the breed is expected to cover substantial distances in the heat at the trot. The ratio of weight to height matters when speed with stamina is sought. The early show Greyhounds came from the coursing grounds but study the latter and put them against the statuesque and oversized (nearly twice the weight of many successful Waterloo Cup winners) hounds exhibited today. Perhaps a track-run should be part of their champions’ qualification!

The claim by the KC that Crufts is a show for the ‘Best of the Very Best’ is in conflict with the critiques produced by the judges they appoint to officiate there. In 2011, the Beagle judge found too many incorrect bites; the 2012 Beagle judge complained of far too many poor fronts; the 2012 Bloodhound judge was disappointed by the bite and the amount of haw in the eyes of the entry; the 2012 judge of Grand Bassets Griffon Vendeen found a lot to be desired in the hindquarters – high hocks, cow hocks and narrow thighs - and in the movement of the entry; the 2012 Rhodesian Ridgeback judge wasn’t pleased with the jaw shape in far too many of the entry; the 2012 Basset Hound judge found the ears still far too long – a persistent fault in this breed. In the championship shows in recent years, even more worrying faults have been reported. Beagles have been shown with short rib cages, distressing movement and poor bites. Bassets and Bloodhounds were found to have incorrect movement and worrying anatomical flaws. Rhodesian Ridgebacks displayed poor feet and a lack of drive from behind. Hamiltonstovares were found to be lacking substance and quality of bone. Norwegian Elkhounds seem to have poor rear angulation as a persistent fault. I would be surprised if these pedigree dogs were not bred from; you do not get healthier hounds from flawed stock. All lacked true type.

Breeds in the hound group provide a good example of how breed differences start. Foothounds tend to be small and slower moving, the hounds accompanying the mounted hunter have longer legs to enable them to possess pace. Hounds which pursued big game like boarhounds, tended to be heavier, higher on the leg and stronger jawed, as the Fila Brasileiro, the Perro de Presa Canario, the Dogo Argentino and the Grand Griffon-Vendeen or the Grand Fauve de Bretagne each demonstrated. The killing hounds, the 'seizers', tended to be more powerful, fiercer, weightier up-front and wider-jawed, as their depictions as 'beissers', in medieval times, as the German bullenbeisser (forerunner of the Boxer) illustrates. The latter two groups, the heavy hounds, were invaluable before the invention of firearms and are nowadays, wrongly in my view, formally gathered into non-hound groupings, such as the Working Group, as categorized by our Kennel Club. This can affect their breeding; they are no longer bred as hounds. Today’s descendant breeds look nothing like them and are not sounder for that. They have lost ‘hound-type’.

It is forgivable to look at the Mastiff in today's show rings, in the Working Group, and overlook its hound ancestry. In his celebrated book 'The Master of Game', written between 1406 and 1413 and the oldest English book on hunting, Edward, second Duke of York, started his eighteenth chapter with these words: "A mastiff is a manner of hound." Such a powerful hound was once deemed to pose a threat to the stags and boars of royal forests and lawfully made lame to stop it hunting. The breed of Mastiff we have today poses little threat to any stag or boar. This modern breed of Mastiff was re-created by 19th century English breeders using stock including the Great Dane, smooth St Bernard and Tibetan Mastiff. It now looks very different from its true ancestors. If it were to be bred in its correct historic mould, it would resemble a heavy hound, with excellent movement and great stamina. It should not have a massive wrinkled head, over-heavy excessive bone and disastrous movement. Such exaggerations ruin breed-type! Compare the Mastiff of a century ago with the ponderous brutes masquerading as the same breed in today’s show-rings!

There is a lesson here for Bullmastiff breeders. Bullmastiff breeders are wrong to look at type in the modern breed of Mastiff and say my breed should be 60% like that. They would also be wrong to look at type in the modern breed of Bulldog and say my breed should be 40% like that. The bull-baiting dogs were athletic and agile - or they didn't live long enough to breed! So, what should a typical Bullmastiff look like? Whether it is modelled on the hunting mastiff or the Gamekeeper's Night-dog, its 19th century role, it must have: a really strong jaw, sound movement, great stamina, considerable substance and great strength, backed by immense determination. There are distinct tangible anatomical features that enable these qualities to be displayed in the breed. Functional type can manifest itself through breed-type, but not always specifically. Lack of type can spoil a specimen in any breed and reduce its value.

At the end of the last century, the pursuit of absurdly barrel-chested rib cages by misguided Bulldog breeders, led to 'out at elbow' becoming almost a breed feature. It has taken a long time to put that right. The ratio of chest depth to its width is now known to be a factor in the incidence of bloat in dogs. Lung-room comes from a balance between girth of chest and length of rib cage. The Breed Standard drawn up by the British Bullmastiff League at its inception contained this valuable phrase: "...ribs arched, deep and well set back to hips"; today's Breed Standard does not even mention the ribs. The Bullmastiff's distant ancestors needed to gallop; to do so they needed lung-room to sustain the gallop but also no interference with activity from being too short-coupled. The size of the gap between the last or rearmost rib and the leading edge of the dog's thigh is a crucial one; too little allows explosive power but no endurance, too much can produce a weak back through lack of support. A hand's width is perhaps ideal in a hunting mastiff. The Ancient Greeks knew the value of length of back in dogs designed to gallop; Arrian and Xenophon linking it with spirit and pace. There would be value in the Bullmastiff clubs conducting a study on the distance between the point of shoulder and the point of buttock in their dogs. This measurement, which should be slightly more than the height of the dog, will always be linked to the compactness of a dog and its ability to move impressively, with strength and purpose. This relates to breed-type too, as the early specimens indicated.

Substance and great strength come from correct construction and powerful muscular development, very different from a fat dog with heavy bone. There is evidence that puppies bred and fed for 'great bone' are more prone to hip dysplasia. Hip and elbow dysplasia, osteosarcoma and cervical vertebral malformation appear to be more prevalent in the heavier breeds, most of whom are far heavier than their ancestors. Bone disorders in the pedigree dog are becoming more frequent in incidence. Massive round bone is not strong bone; the Foxhound breeders found this to their cost one hundred years ago when the so-called 'shorthorn' period did enormous damage to breeding stock. Flat bone, produced naturally, has long been found to be stronger -- ask any racehorse owner! Why breed large dogs with heavy round bone when such a feature is neither typical nor healthy? Why not rely on historic type? Why breed a terrier that can’t do a terrier’s work?

At a recent Crufts, the Lakeland Terrier judge used these words in his show report: "On the whole the standard of Lakelands at this show were (sic) not of a very high standard, some nice ones, some not so nice, and some absolute rubbish." I do hope those working Lakeland terrier-men who resort to show dog blood occasionally choose wisely! The myth of the association between pedigree and quality is surely finally acknowledged by sportsmen of all styles. At the Scottish KC Championship show a year ago, the judge recorded: "When recognition of the PJRT (i.e. Parson Jack Russell Terrier, DH) took place I was under the impression that we were going to preserve the look of this old type of working terrier, it now seems that some breeders with no knowledge of, or regard for, the traditional type are determined, with the help of judges with no breed type experience, to change completely the character and look of the breed." That, in comparatively few words, sums up very aptly what happens to terrier breeds in the KC show rings. God protect the Patterdale, the Fell, the Lucas, the Sporting Lucas, the Plummer and any other terriers heading towards KC recognition. Performance is soon second to prettiness.

When judging the build of a working terrier, let's be guided by the wise words of our Major Ollivant, writing over seventy years ago: "A terrier that has to work underground must have his heart in the right place; then if his body permits him to do so, he will get there like the good sportsman he is." The only reason why we have working terriers to breed from nowadays is that countrymen who were real terrier-men kept their heads over many years and ignored the financial allure of the KC show rings. They have realized that true type brings soundness and the ability to do the work they were designed for. A well-known show breeder once accused me of being a nostalgist, a lover of the past, not willing to acknowledge the passage of time and clinging to the past – regarding former times as being automatically better times. I merely pointed out that, being 40 years older than he, I could remember the past times that I held to be superior!

Thomson Gray, the great expert on Scottish breeds, once wrote in The Bazaar magazine of 1895: “Fanciers of recent years have tried to alter the original type of Terrier, by trying to engraft on a short, cobby body, a long, senseless-looking head, to get which they had to breed dogs almost, if not quite, twice the size of the original, and to alter the formation of the head. This straight-face craze began in Black-and-Tan Terriers, extended to Fox-terriers, is seen in Bedlington Terriers, is now contaminating the Collie, and is threatening our national Scottish Terrier.” Half a century later, the knowledgeable Vesey Fitzgerald was writing in his The Domestic Dog of 1948: “It would be true to say that no show champion of 20 years ago – certainly in the terriers, and in most other breeds as well – would stand a chance today. In the terriers, at least, their heads would be described as ‘coarse’; and none of the old champions, so highly regarded so short a while ago, would, of course, be ‘standing up on his toes on stiff and useless pasterns’.” Neither of these acknowledged experts wrote their words idly; they cared deeply about true type. Many other writers with a deep knowledge of dogs have long been warning of the danger of fads creeping into breeds and totally ruining their classic type.

Fads may be passing indulgences for fanciers but they so often do lasting harm to breeds. If they did harm to the breeders who inflict them, rather than to the wretched dogs that suffer them, fads would be more tolerable and certainly more short-lived. But what are the comments of veterinary surgeons who have to treat the ill-effects of misguided fads? In his informative book The Dog: Structure and Movement, of 1970, RH Smythe, a vet and exhibitor, wrote: "...many of the people who keep, breed and exhibit dogs, have little knowledge of their basic anatomy or of the structural features underlying the physical formation insisted upon in the standards laid down for any particular breed. Nor do many of them - and this includes some of the accepted judges - know, when they handle a dog in or outside the show ring, the nature of the structures which give rise to the varying contours of the body, or why certain types of conformation are desirable and others harmful."

Having watched the judging at the 1998 Crufts on Pastoral Group Day, I can see why such words were forthcoming. Having gone to my first dog show over sixty years ago, attended seven World Dog Shows and innumerable championship shows, I feel, with enormous concern, that things are getting worse rather than better. In his book, Smythe goes on to say that "...the same may sometimes be written regarding those whose duty it is to formulate standards designed to preserve the usefulness or encourage the welfare of the recognised breeds." Encouraging the welfare of the recognised breeds has to be the underlying mission of not just the Kennel Club, whom Smythe is pointedly criticising, but every breeder, every breed club and every judge officiating at dog shows.

In every decade, in the world of the pedigree dog, the faddists are at work, sadly in far too many breeds, promoting, for example, the longer loins and hyper-angulated hindquarters, with hind feet positioned well behind the dog, that have strangely become the norm. I see that admirable breed, the Groenendael, short-stepping, with little forward reach, as upright shoulders, aimed at making the exhibit look statuesque in the ring, are favoured. German Shepherd Dogs, in the days when they were still called Alsatians, were famed for their level toplines and their ability to maintain that topline on the move, with a smooth, effortless, gliding locomotion - much envied by other breed fanciers. No contemporary GSD could win in the ring unless it ‘gaited’, i.e. moved in an artificial manner, without the drive from the hindlimbs every pastoral breed relies on, a sad loss of true type based on historic function.

It is depressing however for any admirer of dogs that can work to read a prominent KC member declare a few years back that people don't want their terriers to go to ground, their Border Collies to herd sheep or their gundogs to retrieve game, they just want pets. What a betrayal of trust, an admission of defeat! A breed that is not physically able to carry out its original task has no right to bear the name of that breed. It is not a question of whether it has to, but whether it is able to undertake its historic role, indeed, whether it is truly a member of that historic breed at all. Do we really want retrievers with no capability for retrieving? Of course, there are some excellent gundogs at Crufts and there are excellent breeders of dual-purpose gundogs too. What we need to do is reject from the show ring, not even allow them to be exhibited, dogs with the kind of structural flaws highlighted by the top show ring judges themselves. It’s not good enough for them just to go card-less; they should be thrown out of the ring, before the judging even starts. A dog show is a livestock show or it is nothing. Dogs that qualify for Crufts with blatant faults represent a severe judgement on the show ring judges who provided them with qualification.

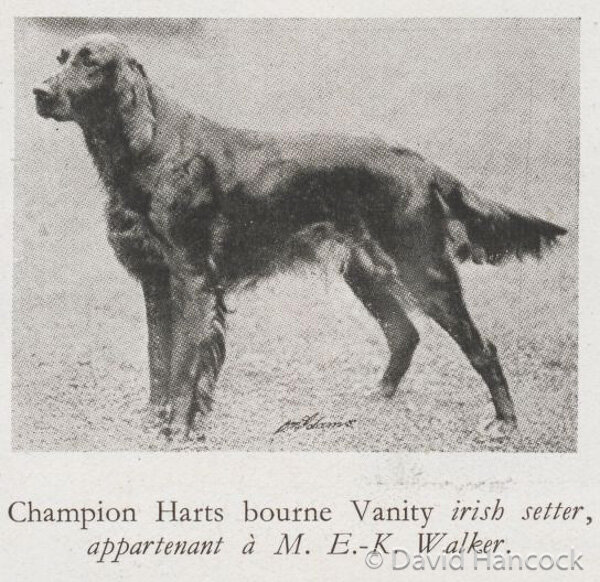

A Crufts-winning Pointer with a high-stepping, forward-reaching Hackney action, which I once witnessed, was in fact in breach of its own breed standard, as promulgated by the Kennel Club which runs Crufts and appoints judges. This Breed Standard states very plainly..."Definitely not a hackney action...Any departure from the foregoing points should be considered a fault..." So here was a specimen of one of our most famous gundog breeds winning at our most prestigious dog show of the year with an easily-identified fault. What is the point of having a precisely-worded standard if a dog can win in spite of it? What kind of gundog judge is it that cannot see such a basic fault in a working dog? Other judges of show ring gundogs are not slow to spot significant faults as these critiques from judges illustrate. North Riding Gundog Club's open show: "I was appalled at the unsound action, especially in Golden Retrievers and Labradors, many of which looked so nice standing but fell to pieces on the move." Other judges looking over Labradors at different shows wrote: "The diversity of type and the prevalence of coarse heads and poor tails gives cause for concern for the future"..."My main criticism is mouths. I found 5 from all the classes which were really bad"..."I would like to mention incorrect mouths. I have never come across so many variations before and some were quite severely wrong." A gundog's mouth is rather important! These remarks by judges were made about dogs bred to a carefully-written standard and change hands for several thousands of pounds. I see big differences between the gundogs on show now and those exhibited when I was young. I can remember English Setters that were just about pure white, hard-muscled and only lightly-furnished or feathered, but admittedly, they were field dogs not show dogs. English Setters and Irish Setters are not now of working type.

A recent show critique on the Irish Setter used these words: "Many had short necks or rather, the neck was the correct length, if only the shoulders and forequarters had been angulated correctly, ...a fault that is being accepted as the correct standard...I hope the two entropians are not bred from." Here are pedigree gundogs being bred with not only a fault in their basic construction but with faulty genes too! In-growing eyelashes or entropian is a distressing eye condition in any breed; yet dogs suffering from this inherited defect can be shown under Kennel Club rules and win prizes. What a situation - gundog breeders knowingly perpetuating physically unsound dogs!

But why breed dogs in the 21st century for a lost function? The answer is that function gave us breed type, with physical soundness. Breeders of British breeds, mainly those competing in the show ring, are sometimes accused abroad of seeking exaggeration, exaggeration to a degree that is harmful and untypical. Those perpetuating our native breeds must remember the function for which that particular breed was developed, whether that function has lapsed or not. Only then can really genuine, historically-correct type be preserved. Every breeder of one of our native breeds has a special duty to safeguard its future; we must never let breeders from foreign countries change type or dictate what our breeds should look like. In his informative book "The Theory and Practice of Breeding to Type", published by 'Our Dogs' eighty years ago, CJ Davies concluded: "...animals nearest to the 'correct type' are those best adapted for the work which they are supposed to perform;" it is so important to remember this when assessing a dog or planning a litter. Breeders, and judges, think hard before you make decisions - the future of all our magnificent breeds of dog are in your hands. Seek traditional type if you are aiming for sound dogs!