1204

EYE-ING THE FUTURE

By David Hancock

In The Sunday Times of the 10th of March 2019 there was an article headlined “’Gremlins’ dog in Crufts row” focussing on ‘a breed designed to have bulging astonished-looking eyes that is being allowed to compete in prizewinning categories.’ The reference was to a breed called the Japanese Chin that vets claim have injury-prone eyes which can easily become cross-eyed. But why pick on this breed when several Toy breeds have the same affliction? Any exposure of genetic flaws in breeds of dog is welcome but why on earth don’t the veterinary authorities speak up or even seek to ban such exaggerations by lobbying the KC fiercely and remorselessly? Eyes so vulnerable to deterioration and accidental damage simply cannot go on being condoned – however stubborn a breed club or council may be. Every breed of dog, especially pedigree breeds under the ‘protection’ of the KC, must be bred as disease-free and least accident-prone as we humans can ensure. Sight is precious!

The breeds in the Toy and Utility Groups tend to have more eye-problems than those in the Sporting Division, where function has long had a role to play in the breed design. Every gundog, terrier or hound breed needs forward sight and unimpeded sight as a prerequisite to successful functioning. Toy and many Utility breeds are purely ornamental and therefore at the mercy of fancier-fad or gradual exaggeration, knowingly or subconsciously inflicted by breeders. Breeds without a field or working function are at the mercy of zealous exhibitors and ambitious judges. Pekingese, Pomeranians, Chihuahuas, Lowchens, Pugs, Brussells Griffons and Affenpinschers, can all display eye-placements not suitable for assisting eye-sight. Eyes that bulge or look too big for their sockets are vulnerable to damage and disease.

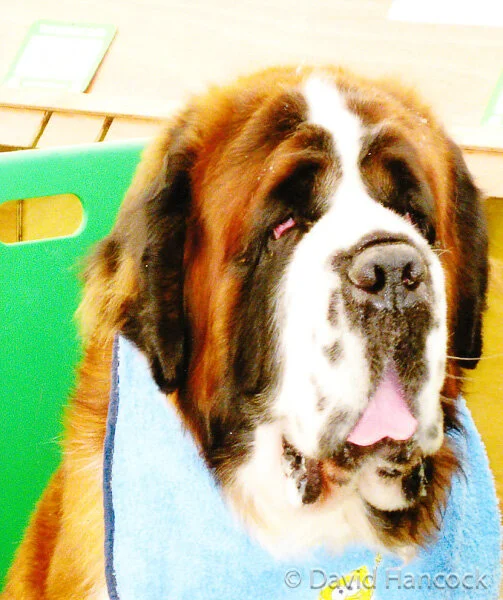

It is perhaps a reflection on our selective compassion that we hear more about guide dogs for the blind than we do about blind dogs; both need our committed support. I was once asked by a precocious child why there weren't any guide dogs for blind dogs; it is a fair question, grown-ups don't often ask such an original question. There are records of sighted dogs acting quite instinctively to assist blind dogs in their movements. I know of a blind Whippet which went hunting daily, despite its disability; I admired its owner for giving it such spiritual outlet and release from perpetual handicap. We should treasure sound eyesight in our dogs both through breeding programmes, to reduce the incidence of inherited eye conditions, and by monitoring the sad restrictions on sight imposed by faddish breeders. No dog enjoys wearing blinkers! And no Mastiff or St Bernard gains from having red-raw eye-rims or eye-lids so loose that grit and other foreign bodies can enter and give irritating discomfort. Dogs can’t use a hanky!

How many human beings have you come across who tolerate their forward view being mainly obscured by their own hair? Yet we seem content to produce dogs, usually in canine beauty contests, with such a degree of hair before their eyes that their sight, and therefore their quality of life, is diminished. That, to me, is slavery to a fad rather than compassionate concern for dogs. One owner of a dog exhibited at Crufts, with hair covering its eyes completely, assured me, firstly, that this breed had managed with such a liability for a hundred years so what was the problem, and, secondly, his breed had to look like that in order to qualify for Crufts! The first reason is untrue; breeds have got hairier and hairier as the closed gene pool magnified the feature. The second reason is a sad reflection on the show scene; any human whim which, when exercised, discomforts dogs, needs to be countered.

The much-queried European Convention for the Protection of Pet Animals (ETS 125) aims, rightly or wrongly, to counter those elements of pedigree dog-breeding which affect the welfare of the dog. It expresses concern over the 'abnormal size and form of eyes and eyelids' and seeks reconsideration of breed standards' where the wording could lead to discomfort for a dog. There is, perhaps understandably, strong opposition to this convention in Britain. This could eventually lead to a heated discussion on what matters more, breed type or the morality of breeding discomforted creatures. In the times we live in, I believe that the arguments over the latter will win. The wording of Breed Standards here on eyes, i.e. what they should look like in a breed, are questionable. It would be sensible if our canine hierarchy gave this some early attention. But sporting breeds can have problems around the eyes too, affecting their vision.

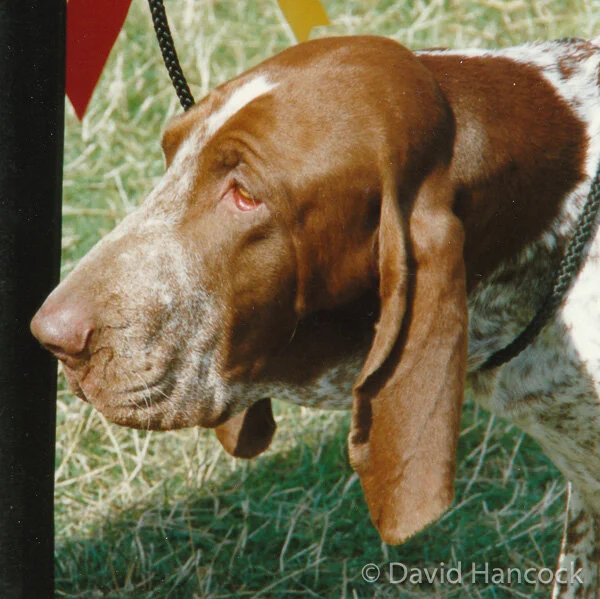

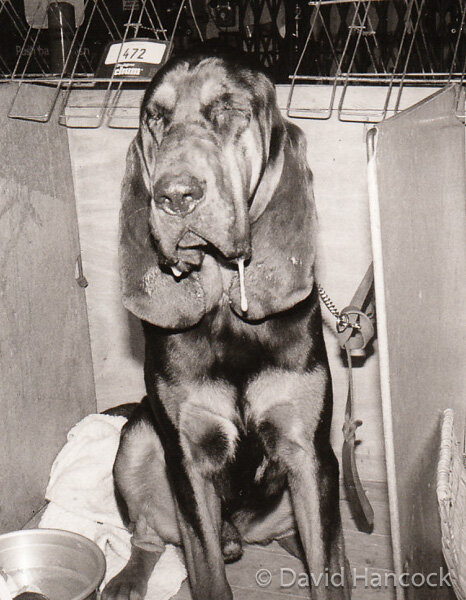

The Bracco Italiano can display ‘haw’ or loose eyelids, as can the Basset Hound. The Bloodhound must not have sunken eyes but if you tour the Bloodhound benches at Crufts, you can see any number of them. How did they qualify? By not obeying their own breed standard? The Clumber Spaniel is actually allowed to display haw 'but without excess'. Will it take the European Convention to establish the degree of excess permitted? Haw, or loose eyelids, is just what a hard-working gundog does NOT need, but it is permitted in the Sussex Spaniel, and the Basset Hound, too. Red-rimmed eyes are surely red-rags to morally-vain bulls, why walk into that trap? No working dog can obtain anything other than discomfort from loose eyelids; why permit it in an officially-sanctioned breed standard? It gives those who wish to dictate to dog-breeders all the ammunition they need.

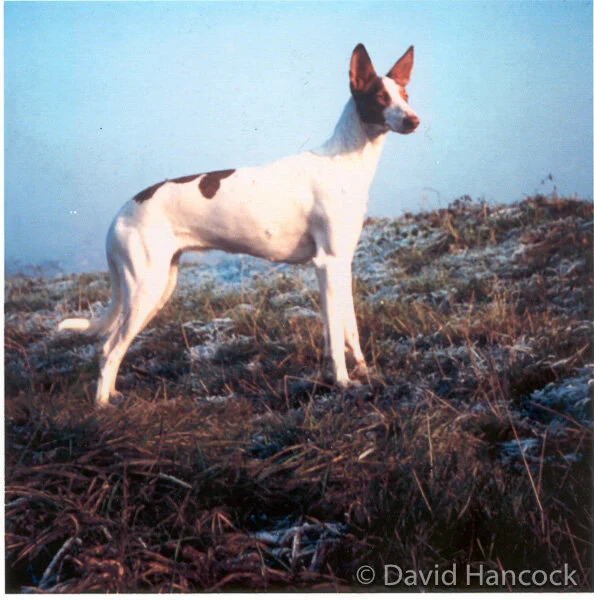

If you find joy in watching a sighthound, say, in southern Europe, ears raised in concentration, eyes acutely focused, nose quivering, instinctively scanning the ground ahead of it, you appreciate fully the close link between sight, scent, and hearing too, in sporting breeds. Hunting by sight has been highly developed in such breeds by man for centuries. Distant eyesight means more to dogs than to us; that alone is reason enough to prize them and strive to protect them. It is believed that dogs have 20/75 vision, meaning that they are able to see clearly an object from 20 feet away that a human with normal vision would see at 75 feet away. Cats have roughly 20/100 vision and horses 20/33, closer to ours. But dogs have vastly superior night vision and the detection of movement. They thrived as predators because of their combined better-developed senses of sight, hearing and smell. The low-light vision of dogs is greatly superior to ours too, facilitating hunting at night.

Dogs are more aware of events around them than human beings. Their eyes are set on their heads at a 20-degree angle, whereas we have our eyes set looking straight ahead. Dogs have a much wider field of view than we do, around 250 degrees against our 180 degrees. Perception of depth depends on binocular vision, which is the visual area where the two eyes overlap. The greater the binocular field, then the greater the depth of perception in a species. We excel in depth perception, with a visual overlap of around 140 degrees; dogs have a visual overlap of around 80 degrees only. They need all the help they can get in depth perception. By limiting further their binocular vision we increase their burden more than we realise. This additionally-imposed limitation is one dogs could do without – especially those with a working or sporting function..

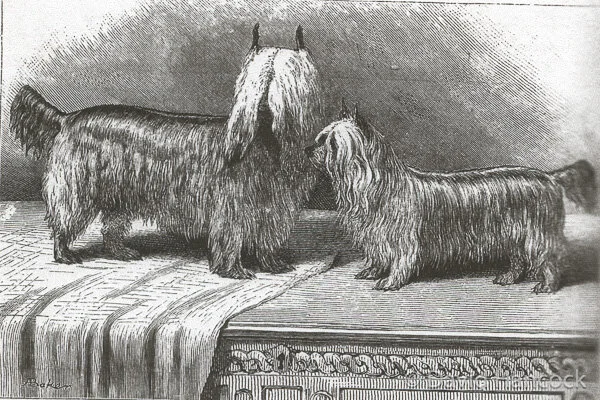

Yet, in breeds like the Soft-coated Wheaten, Black Russian, Skye and Kerry Blue Terriers, the Schnauzers, as well as many ornamental Toy and Utility breeds, we appear to be doing our utmost to limit their forward vision with excessive fringes, with scant regard for the welfare of the dogs. We cannot knowingly do that and then complain about interference from animal-welfarists, on the grounds that these breeds are safest in our hands. If you 'fancy' a breed, surely you do so out of affection, not exploitation. As Shakespeare wrote: "Tell me where is fancy bred, Or in the heart or in the head? How begot, how nourished...? It is engendered in the eyes." There is not much nourishment from the hearts of some breed fanciers. An obtrusive heavily-hanging fringe is not a feature of many wild dogs, neither is the distinct squint of some Chows and Shar Peis. Nature provides living creatures with the senses needed to survive, what right has man to impede these basic senses? By what mandate do breed fanciers inflict limitations on their breed's sight? Certainly not out of a truthful regard for breed history, impeded sight is a recent innovation in dogs. The half-closed eyes on a Chinese Shar Pei look painful and are spoiling its quality of life.

A show ring judge could be forgiven, when judging heavily coated breeds, to state 'I cannot see the dogs’ eyes so I can't possibly judge that key feature'. A show veterinary surgeon could be forgiven for saying 'this exhibit has excessively protruding/sunken/hawed eyes and is not fit for the ring'. A breed specialist could justify stating that since this exhibit does not conform to the Breed Standard, I will not allow it into the ring. The Kennel Club could stipulate that any exhibit with impeded sight must not even be considered by the judge. A breeder with high moral standards could be applauded for taking the stance that the breed has departed so far from its roots that, out of regard for its ability to see adequately alone, a rethink is needed. Breed Councils could cease to hide behind their non-executive role and insist on action to facilitate better vision in their breed. But none of these things will happen; only much-maligned legislators will act, everyone else will wring their hands and hide behind the feeble excuse of breed purity. How sad!

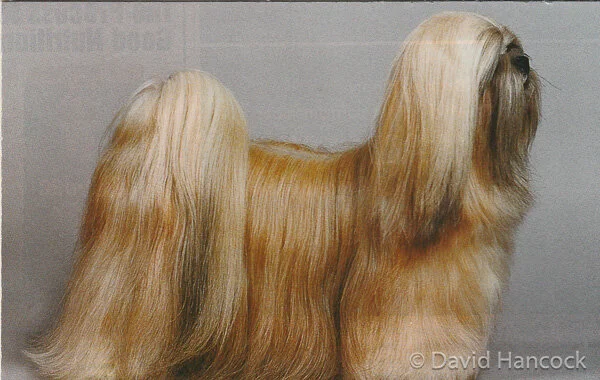

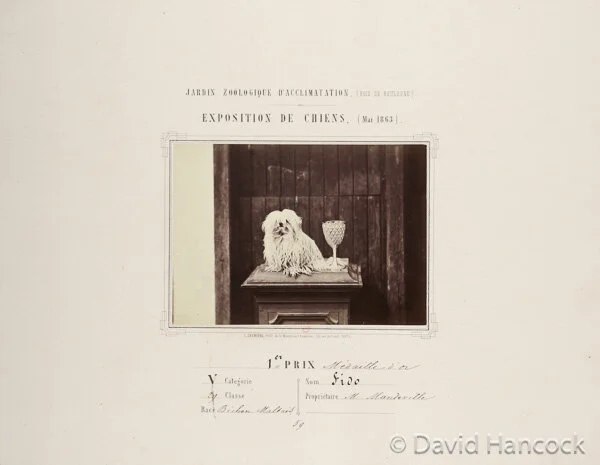

In his masterly The Conformation of the Dog (Popular Dogs, 1957), the veterinary surgeon and successful exhibitor RH Smythe wrote: "Dogs such as the Kerry Blue with a huge bunch of hair descending from the forehead between the eyes will have the greatest difficulty in seeing at any time with two eyes at once any object situated in front of them. It is amazing how such dogs as Old English Sheepdogs and some foreign breeds such as the Tibetan Terrier with masses of hair bushed out all over the face manage to see at all!" Over half a century later, the situation if anything has got worse; when is action going to be taken by those with responsibilities for breeds of dog in Britain? Is it at all surprising that an outside body has thought it timely to act in the protection of dogs? Breeds like the Tibetan Terrier, the Lhasa Apso, the Yorkie and the Maltese have had limited vision for far too long.

In his equally valuable Judging Dogs (Gifford, 1972), Smythe makes these observations: "The colour of the eye or of the eye rims, has no effect on vision so one may wonder whether those who first drew up the Standards thought that a dark eye was superior in vision to a light eye, or if, after all, the whole subject of the standard was to make each breed in its own way, pretty." If his final comment is correct, so much for breeders having the best interests of their particular breed at heart. In a further observation he points out that "The respective Standards make no reference to the fact that certain breeds have flat faces, frontal eye placement and binocular vision while others have long heads with prominent muzzles separating the two eyes, each of which has its own separate field of vision. Probably the reason is that there is apparently no cooperation or means of communication between the people who drew up the Standards in differing breeds."

That last comment is a direct reflection on our Kennel Club, who have taken upon themselves the full and final responsibility for Breed Standards. Eyes are a key part of not just a dog's basic senses but of its anatomy too. The construction of the dog affects the way it uses its eyes, the neck and the skull especially. If you accept responsibility for the word picture of a breed, then you can in so many ways decide the fate of that breed. If the word picture allows the dog of a breed to become handicapped, then surely the body responsible for that word picture has a case to answer. If it is not a declared fault for a dog's eyesight to be impaired by its coat or its eye design then it is a fair question to ask, why not? If for over a century, a body which has based its whole raison d'etre on the improvement of dogs, has merely watched actual deterioration, step forward the animal activists-proper – here is a real welfare issue!