1207

ROUNDHEAD OR CAVALIER?

By David Hancock

In the April 2019 edition of that admirable magazine Dogs Today, Alessandra Pacelli wrote a disturbing article about serious health issues in the breed of Cavalier King Charles Spaniel. Her opening words were alarming: “The way the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel has been bred to look has resulted in crippling neurological conditions. New research suggests that breed show judges could detect the presence of Chiari-like malformation and syringomyelia by visual checks alone…” When you think back to the scandal erupting from the revealing TV documentary Pedigree Dogs Exposed a decade or so ago on this breed, you wonder if the canine authorities are capable of putting breed-specific conditions in order – or are the lovers of this particular breed just indifferent to the health of their allegedly much-loved breed? The article in Dogs Today quotes a study by the University of Surrey that reads: “This recent change in shape is significantly different to traditional breed standards and current research has shown that it increases the risk of developing Chiari malformation and syringomyelia…over time can cause irreversible damage to a dog’s spinal cord.” The article stated that other breeds can be afflicted too – Chihuahuas and Affenpinschers, but I suspect more Toy breeds might well be prone to such a condition.

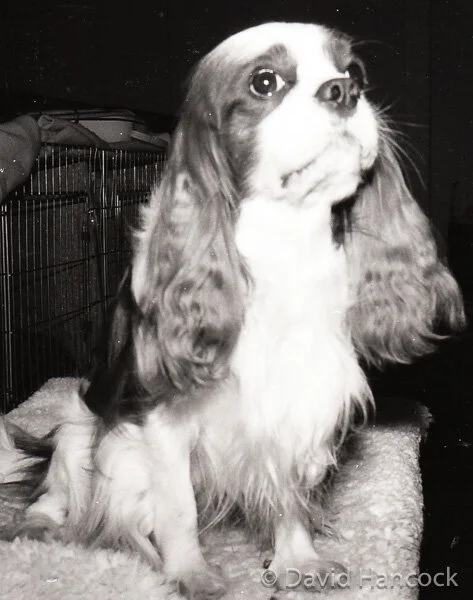

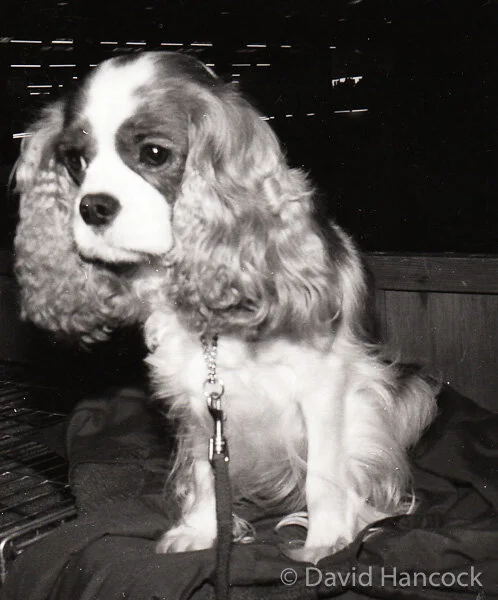

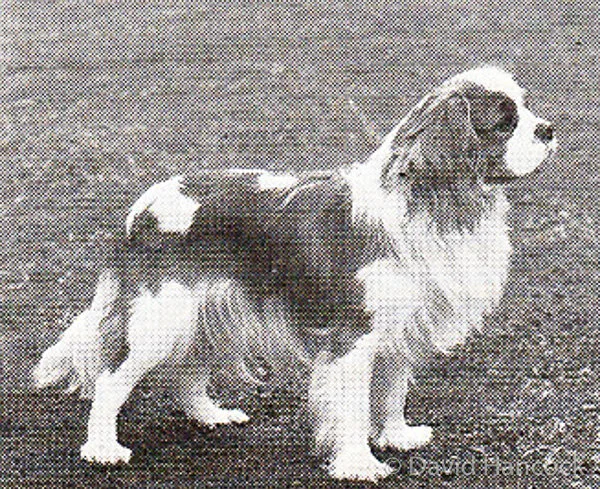

Ironically, it was only in 1926, when the preference in the show ring for the squashed-nosed breed of King Charles Spaniel was challenged by a visiting American, Roswell Eldridge, that the breed of Cavalier was created. Disappointed by the ousting of the longer muzzled dogs as depicted in so many old paintings, he instigated its restoration through prize-money incentives. At first this restoration was slow and hard going, with the breeding stock being the longer muzzled throw-outs from pedigree litters. In due course the restored variety was stabilised as the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, with its own separate breed club. Twenty years after the Eldridge initiative the restored breed was recognised by the Kennel Club as a distinct breed. There are a number of contemporary pedigree breeds of dog which could benefit from a visit from a latter-day Roswell Eldridge to restore them to their historically-correct anatomy. If you look at the annual registrations of the two regal breeds you will quickly see which one the public prefer. In 2018 for example, 3,700 Cavaliers were listed against only 106 King Charles Spaniels. I would like to think that part of that popularity is rooted in the modern dog owner's increasing distaste for exaggerated features in a subject creature to suit the misguided whim of man. But now the ‘created breed’ is itself under fire. The dome-head, squashed-nose gene has clearly not been suppressed!

The word picture of the King Charles Spaniel, listed as a Toy breed, approved by the Kennel Club, has at last been amended. This breed description, until recently, demanded as a characteristic a "distinctive domed head", a skull large in comparison to size with a "very short" nose and "very large" eyes. Well domed heads are usually the sign of genetic freaks or 'sports'. When the dog's skull is intentionally designed to be larger than its pelvis, you invite whelping difficulties. Very short muzzles and very large eyes entice exaggeration and end up being harmful to the dog. Too short a nose leads to respiratory problems; too short a jaw leads to dental problems and the pursuit of very large eyes leads to drying of the cornea, corneal ulceration and conjunctivitis. Chronic sinusitis, protrusion of the eyeballs (sometimes resulting in the dog's eyes literally popping out) and outward turning of the eyes, handicapping binocular vision, are also features of breeds with excessively short muzzles and large prominent eyes. Why do breeders wish to harm their own dogs? Why did the kennel Club allow such harmful words to be breeders’ guidance for so long and only changed because of external pressures?

The more popular Cavalier King Charles Spaniel is also listed as a Toy breed by the KC but it is good to see its Breed Standard stressing that it should be "sporting". The much quoted 19th century writer on dogs, 'Stonehenge', has written: "The Blenheim and King Charles Spaniel will be described under the head of toy dogs, to which purpose alone they are really suited, though sometimes used in covert shooting", indicating their Toy dog image yet the retention of working potential. The next King Charles will have a unique canine achievement. Despite the long history of dogs being favoured by royalty in Britain, only two breeds of dog, one created from the other, have royal titles: the King Charles Spaniel, smaller and shorter in the muzzle, and the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, only recognised by the Kennel Club in 1945 but representing the earliest type of companion spaniel as opposed to a Toy spaniel. Their association with King Charles belies the much longer history of royal patronage of small spaniels. A story is told of James II, fleeing from a sinking ship, refusing to return to the ship to save sailors but returning later on hearing that some of his favourite little spaniels had been left behind.

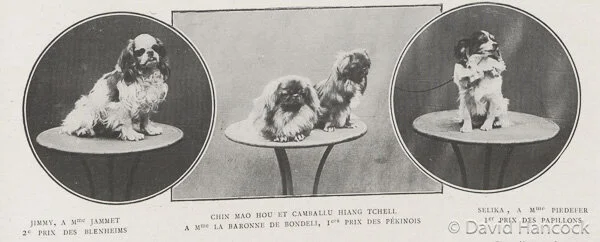

Small ornamental dogs with very short muzzles have long been favourites in royal households across the world. Breeds like the Pug, Pekingese, Japanese Chin, Tibetan Spaniel, Lhasa Apso, Maltese and the Brussels Griffon are prized today as companion dogs in the same tradition. Some of these breeds originated in the Far East and, were either brought back to Western Europe by traders like the Dutch and English in the 17th century or transported much earlier along the famous Silk Route as prestigious gifts, or bartered as goods between the Orient and the Levant. Similarly, small parti-coloured beagle-sized spaniels were favoured in the European courts and feature in many well-known paintings of the 17th and 18th centuries. In due course, perhaps inevitably in the days before pedigree dog breeds became registered, the dome-skulled, pop-eyed, squashed-faced Toy spaniels interbred with the small European ornamental spaniels so as to blur the differences between the two breed types. Distinguished artists such as Reynolds, Van Dyck, Riviere, Stubbs and Landseer have depicted such dogs on canvas, leaving us with a good idea of their conformation and type. In the Sportsman's Repository of 1820, it was recorded that these "delicate and small carpet spaniels have excellent noses, and will hunt truly and pleasantly, but are neither fit for a long day nor a thorny cover".

Throughout the last century, increasingly, the Toy spaniel type prevailed over the small sporting spaniel style, mainly because genetically a short muzzle is dominant. With the advent of dog shows, this flatter-nosed, more prominent eyed version was for a while endorsed. The originally-imported toy spaniels were probably black and white but after inter-breeding with the small sporting spaniels, came the red and white, the solid red and the black and tan, all loosely referred to as King Charles spaniels. Then one or two noble families began to develop their own strain, notably the Howards and the Churchills. In time the latter became known as the Blenheim spaniel, to commemorate the Duke of Marlborough's pet which accompanied him at the Battle of Waterloo and then into retirement. At the early dog shows, the Marlborough Blenheims were always less favoured than the toy spaniel with the bulging forehead and the retrousse nose. When the Toy Spaniel Club was formed in 1885, the colours in the breed were each named differently to produce: the King Charles (black and tan), the Ruby (solid red), the Prince Charles (tricolour) and the Blenheim (red and white). The King Charles was a deep glossy black off-set by rich mahogany tan, usually with the heaviest coat and the shortest muzzle. The Ruby was the richest of rich deep red, the rarest coat colour and not with the most profuse coat in the breed. The Prince Charles variety produced the most handsome coat and was often crossed with the Blenheim to enhance the richness of the tan marking. Today, the Prince Charles variety is called less distinctively the Tricolour; perhaps the current bearer of that royal title, a dedicated conservationist, should reclaim his breed.

Bewick, in his History of Quadrupeds of 1790, wrote similarly: "The Cocker is lively, active and pleasant, an unwearied pursuer of its game, and very expert in raising woodcocks and snipe...Of the same kind is that beautiful little dog, which in this country is well known under the appellation of King Charles dog..." 'Idstone', writing at the end of the last century, referred to a "genuine King Charles...used with great success for woodcock shooting". A little earlier, Youatt was writing on the Blenheim spaniel: "From its beauty and occasional gaiety, it is oftener an inhabitant of the drawing room than the field; but it occasionally breaks out, and shows what nature designed it for. Some of these carpeted pets acquit themselves nobly in the covert. There they ought oftener to be..."

HS Lloyd, perhaps the greatest breeder of Cocker Spaniels in the last century and having deep knowledge of the history of all spaniels, considered that both the Duke of Marlborough's and King Charles's breed were "much more likely to have been of the distinct breed of cockers..." Small cocking and flushing spaniels were utilised over most of Western Europe in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. There are striking similarities between the Cavalier and the Dutch decoy dog, the Kooikerhondje, the small red and white spaniel-like sporting dog. Decoy dogs were especially valuable before the invention of firearms or before firearms had extensive range.

Their role was to arouse the interest of inquisitive ducks by their agitated antics and the seductive waving of their well-furnished tails. Having captured the interest of the ducks, they then enticed them towards skilfully concealed nets or along ever-narrowing waterways into carefully positioned pens. Such dogs were once well known in Britain and were usually red-coated, being referred to by gypsies as "ginger 'coy dogs". If you watch a Cavalier using its tail vigorously when hunting, it is easy to visualise it acting in a decoy dog role.

The Cavalier, sadly as with nearly every pedigree breed nowadays, has its share of inheritable diseases: hereditary cataract, luxated patella, cardiovascular problems and episodic collapse have been reported in the breed. More recently, mitral valve disease has occurred, leading to veterinary surgeons being asked to record cases and 90 breeders meeting to discuss monitoring and possible control schemes. This, commendably, has the ring of responsible action by the breed clubs concerned. Such a charming breed deserves nothing less. Arnold Chiari syndrome is affecting an increasing number of young Blenheim Cavaliers. Syringomyelia is believed to be carried by 80% and 90% of Cavaliers have a heart murmur by the age of 10. These are worrying times for this popular little breed.

Is this breed to be a ‘roundhead’ or a ‘cavalier’? A roundheaded Cavalier has a 1 in 60 chance of syringomyelia compared to just 1 in 2,000 in other breeds and are more likely to develop mitral value disease than other small breeds. A diligent royal patron could be a force for good here. The next King Charles could continue a timeless royal example by accepting formal patronage of these breeds and spearheading their pursuit of a healthier future. In Macaulay's History of England it's recorded of King Charles II that: "he might be seen before the dew was off the grass in St. James's Park, striding among the trees, playing with his Spaniels and flinging corn to his ducks, and these exhibitions endeared him to the common people, who always like to see the great unbend." This attractive, affectionate, endearing breed has the natural gaiety to make most of us unbend. The two Carolean breeds are distinctive in name, handsome in appearance and slightly bossy by nature. Long may they reign! But the ‘roundheads’ must not triumph over the un-domed headed varieties, work for an animal welfare-conscious monarch.