1229

CAN THE SPORTING DOG SURVIVE?

By David Hancock

Nearly half a century ago, I wrote an article for 'Country Life' magazine with that very title. My concern then was the increasing incidences of inheritable conditions and the absence of health clearances which could help considerably in breeding many of them out. That remains a concern. But since then our leading animal welfare charity has successfully campaigned against the use of sporting dogs and modern urban lifestyles have conspired too to downgrade our ability to enjoy sporting breeds of dog. These two pressures are not entirely separate; urban living denies many the opportunity to savour and therefore appreciate how the countryside is managed. This does not seem to prevent quite a number of town-dwelling lobbyists from expressing remarkably firm views on country matters.

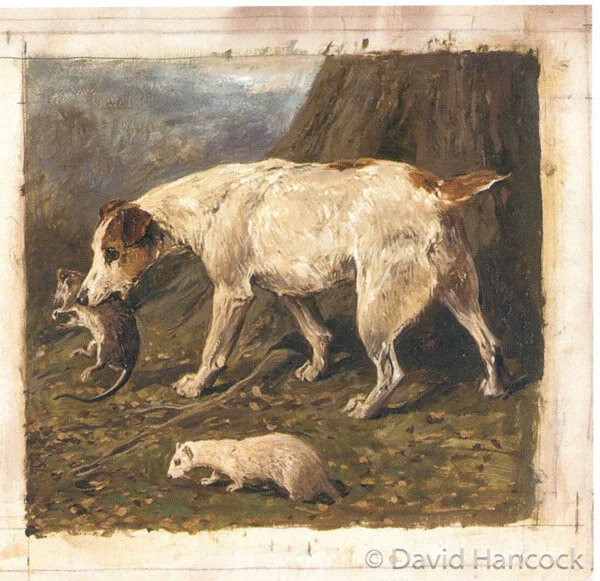

When I managed an historic country estate it was a ceaseless battle to conserve it, one of the bigger threats being vermin. We killed mink to save our wildfowl population; we killed magpies to protect nestlings; we shot grey squirrels to prevent severe damage to our young plantations. The estate was conserved with its rich diversity of wildlife because of these efforts. The visiting public didn't always understand the need; Larsen traps were often destroyed. The British countryside looks largely as it does because, over the centuries, vermin have been controlled. Not many members of urban-dwelling Britain have witnessed a grey squirrel eating a live blue-tit or seen a magpie swallow a nestling-songbird alive. There are few opportunities today to watch terriers kill hundreds of rats around a rick.

This background is important, not to try to justify country sports, that is more a matter of conscience based ideally on informed opinion. But it is vital information if the urban dwelling dog owner is to understand the sporting breeds, their characteristics, their needs and their construction. It is not good sense to expect a gundog to behave like a terrier, a sighthound to have the same temperament as a scenthound, a Pointer or a setter to have the same instincts as a Saluki. Much is made quite rightly of conserving precious old buildings; far less is made of the similar need to conserve our living heritage. The sporting dog is part of Britain's living heritage; in the next decade we could lose not just 20,000 hounds of the pack, but betray our sporting forefathers by breeding gormless gundogs, timorous terriers and supine sighthounds. One of the latter, the Russian Borzoi, is now more a fashion-model of a breed than a fast hunting dog, once famed for its wide-ranging ability as a coursing dog, used to catch wolves and foxes alive – for their pelts, a skill easily employed when scientific culling or ‘rounding-up’ for marking or to be moved somewhere else. When the solar flare afflicts Mother Earth or we are struck by a huge meteorite, where are our hounds to feed us!

As our various breeds of dog were developing, function fashioned form. Breed type often reflected local preferences or breeders' whims, but the phenotype of each breed was decided by function, not by preference or whim. Terrain or country usually decided, in pack hounds, the size of the hound, just as the grouse moor shaped the setter breeds. Colour and coat texture apart, most terrier breeds used as earth-dogs resemble each other. The need for retrievers in the shooting field gave us our highly popular retriever breeds, which were proficient enough to find wide-ranging employment away from the sporting world. A change in the needs of shooting men brought a whole range of HPR breeds to us, as versatility triumphed over specialisation. But whatever their place of origin, every sporting breed developed from use not cosmetic appeal.

My worry is that if country sports decline and as fewer dog-owners witness the sporting breeds in action, the threat of spiritual starvation, anatomical flaws and diminishing instincts looms larger. I believe that ideally every dog owner should, firstly be aware of his breed's natural function, secondly go out of his way to allow the exercise of that function in some way and, thirdly, be aware of the anatomy which permits his dog to carry out its original function. I have neighbours who buy expensive trendy dog-coats for their spaniels but never let them 'work' the many local hedgerows, despite the dogs' obvious eagerness to do so. This is a form of spiritual starvation for the dogs. I also live near an enthusiastic couple owning Dachshunds, once a respected hunting breed, with all the instincts of such a dog. But study the descent of this once-game little breed in the last century, from active hunter to elongated, legless exaggeration of its former self, to see the damage done. Despite its anatomical failings, the Miniature Smooth-haired Dachshund has increased its registrations by 22% since last year and by 179% since 2008, to record over 7,000 entries. I do hope there is pressure within the breed to favour them with longer legs, a shorter back and more daylight under the breastbone or ‘keel’.

Many years ago, when I was working away from home, I used to stretch my legs on Salisbury Plain, missing exercising my own dogs. A colleague had a young Pointer which he never fully enjoyed. I persuaded him to let me take the dog with me on my runs. When I did so and was away from roads and people, I deliberately took the dog into the wind to savour the airscent coming its way. It was a joy just to see that dog, with its head high and its nose well forward, just searching the breeze for the scent of game. Never trained for the field, it adopted the classic 'pointer-pose' quite instinctively, its whole body enraptured by the experience, releasing years of pent-up innate urges. Years later, when I unexpectedly came across this dog again, it went into ecstasy when greeting me, to its owner's mystification. If you want to forge a special relationship with your sporting dog, give it spiritual release!

I have the greatest admiration for those who race their Afghans, take their Irish Wolfhounds lure-chasing or start their gundogs on working tests despite their own lack of expertise in this field. When I have judged the latter, it has always struck me how nice these owners were and how contented their dogs were too. It is so good to hear of tracking trials for Bloodhounds, water tests for Newfoundlands and Dalmatians being used with carriages again. Both these two last-named breeds have a sporting background. Gundogs are valuable assets in drug-searches, guiding the blind or locating arms and explosives. In America, Airedales have their own specific hunting trials; can we really not do so here? I live near dog owners who get upset when their terriers are combative and feisty but are unconcerned when their dogs bark all day, every day. Terrier spirit is part of every sporting terrier's make-up, it comes with the dog and is not difficult to redirect.

One day in the future, it may be the democratically-expressed view of the British people that hunting with dogs has to end. Rather than wring our hands, and however much opposition this brings, we should plan substitute activities for our sporting dogs. I would rather see hunting the 'clean boot' than no hunting at all. I'd rather see Deerhound racing than no Deerhound activity, however unsatisfactory as a fall-back. Whippet racing and hound trailing are established sports but comparable outlets could surely be found for other hound breeds. Some countries run underground, i.e. subterranean tests for their terriers, which the dogs hugely enjoy. Bark-pointers, like the attractive Finnish Spitz, need an outlet too, although I'm not too sure we want many puffin nests located by Lundehunds for egg-eating purposes but certainly for nature-studies. But naturalists and conservationists have realised how dogs can help them in their work, their scenting skills and remarkable detection of animal movement proving of value.

If sporting breeds are to survive there must be a planned renaissance, not an abrogation of responsibility for breeds we specifically bred and developed over several centuries to assist us in the sporting field. It would be a major step forward if breed clubs took up this challenge, although I suspect that challenge certificates have more appeal for them. Just as the UKC in the United States fathers a wide range of field activity for dogs, so too could our own KC, extending their field trial and agility interest. Sporting organisations too could cut their losses and diversify their sporting agenda, in the interests of the hounds alone, if only to have the canine ingredients of a rebirth one day, should field sports regain favour. To neglect the best interests of the dogs would be shameful. Positive thinking is called for, not intellectual collapse. Climate change too can revolutionize our use of sporting dogs.

Throughout our social history as a nation, changing attitudes have influenced our use of dogs in the name of sport. Barbaric activities like badger, bear and bull-baiting, rat-killing competitions and dog-fighting contests have rightly been outlawed. Nevertheless, we still prize and perpetuate that canine gladiator, the Bull Terrier, even if some legislators retain the view that once a fighter always a fighter. This irrational approach doesn't extend however to Zulus, once a superlative martial race or the Vikings, as my peace-loving Danish friends point out to me, with some amusement. The spirit behind the trail-hound and Whippet racing, the Bloodhound packs which hunt a human trail, lure-chasing with Irish Wolfhounds and even nocturnal rat-catching in a maggot-factory, as the late Brian Plummer conducted, provides such encouragement for the future of sporting dogs. Perhaps, sadly, the single-issue lobbyists have them too in their sights.

There was a disturbing article in The Times of the 25th of June 2019 under the headline: “Fashionable breeds are hounding out terriers”. It was pointed out that British breeds intended for hunting or a hard day on a farm are increasingly falling out of favour, suggesting that owners find them too hyperactive for city life. Whilst there may be some truth in that, the greater danger is when such dogs lack instinctive skills such as ratting and hunting, preferring the hearth rug and the nearest sofa. The Scottish Terrier is the latest terrier breed to go on to the KC’s “at watch” list due to falling numbers. Irish and Welsh Terriers also appear on the list of breeds with fewer than 450 registrations a year. Eleven breeds of terrier now have ‘vulnerable status’ after falling below 300. The Norwich Terrier fell from 172 in 2010 to only 81 last year. Only 4 Manchester Terriers were registered in the first quarter of 2019. In 2008 the Border, Staffordshire Bull and West Highland White Terriers were among Britain’s most popular breeds; all three have since dropped out of the top ten. Rats are an enormous threat to both crowded cities and agricultural industries; poisoning them is not without risk to human health – terriers kill them quickly and ensure their numbers are controlled. We need rat-hunting terriers!

No sporting dog can triumph in the field without the physique needed for the sport concerned; as country sports are curtailed the challenge is to retain the working model not the prettiest one. The best dog show judges retain a concept of a breed's purpose in the ring; their critiques sometimes make disturbing reading. One recent critique, from a Lakeland Terrier show judge, made the scornful comment that it should be the fox that runs away from the Lakeland, not the other way round! The Glen of Imaal judge at Crufts in 2003 found..."quite a few weak jaws and that would never do in my view for what they were originally bred for." At Crufts in 2001, the Irish Setter judge reported: "Narrow fronts, lack of bone, upright shoulders, narrow chests with no heart or lung room, weak backends, poor movement. I would be very surprised if many of these could work as a gundog, the job for which they are bred." At the same show the Bedlington Terrier judge stated ..."some lacked the bone and substance required in a working terrier." It is worrying that our top show should reveal such flaws in sporting dogs.

Just over a hundred years ago, the great Bloodhound breeder, Edwin Brough, recorded: "The greatest benefactor to the ancient race (ie the Bloodhound) is the man who breeds intelligently, and supports both trials and shows, but there will always be people who are unable to devote time to both, and the trialer should remember that he will always be greatly indebted to the showman, and the showman should bear in mind that he owes the excuse for his existence to the trialer...their conception of the ideal hound should be the same." These are wise words from a gifted breeder; without field use many breeds lose the functional anatomy essential to sporting success. As fewer and fewer dog breeders take part in activities involving field sports, the functional aspect of their breed's phenotype can be lost sight of, and that is not good for any breed.

Many sporting breeds have translated to the show ring, as the Beagles, Basset Hounds, Bloodhounds, Otterhound, nine sighthound breeds, as many terrier breeds and all the gundog breeds testify. But distinct breeds like the Harrier, the Welsh Hound, the Dumfriesshire Foxhound and the English Basset have yet to. Already the superbly-bred Dumfriesshire pack has been dispersed and sold, mainly overseas, a very sad loss of world-renowned blood. It is ironic that so many simply outstanding dogs will be lost to us forever in the name of animal welfare. It is for the democratic process to decide such things eventually, but every sporting dog admirer must realise that this is just a beginning, gundog breeders beware!

For a nation which has given the world a score of distinguished sporting breeds, many of them preferred to the local breeds on sheer merit, we must now work to ensure that all the dedicated work of our forefathers is not thrown away. A survey of just one native breed, our Fox Terrier, indicates the peril, both in type as well as numbers, the new century poses for the breed. In 1910, over 1,500 smooths and 1,300 wires were registered; in 2018 these numbers had fallen to 126 and 576 respectively. The snipey jaw, the upright front, the fluffy coat in the wires and the loss of physical stature, as well as terrier-spirit demonstrates the threats to the breed’s survival as a sporting dog. Breeding them for show ring success has not just altered their type but undermined their ability, perhaps their eagerness to hunt. That may suit the pet market but it’s no good for the breed as a vermin-controller or wildlife protector! Such a decline reflects the whole sporting dog scene as a whole and it’s deeply worrying.