1244

BULLDOGS NEEDING RECOGNITION

By David Hancock

We tend to think of ‘the Bulldog’ as a purely British type of dog and see the KC-registered variety as the exemplar. But the word bulldog denotes a function not just a recognised breed of dog. Dogs brave enough to face and then control a bull were valuable dogs in quite a lot of countries. Sadly, the word is usually associated with the cruel ‘sport’ of bull-baiting rather than the admirable willingness of cattle farmers’ dogs to face a one-ton, horned and usually very angry, very determined great beast. Dogs prepared to take on a n enraged bull were usually descendants of the ‘beissers; from the medieval hunt, called ‘bullenbeissers’ in central Europe. Depictions of such dogs reveal a strong-headed, utterly-determined but agile dog - its agility essential for its survival. The farmer’s Bulldog was very different indeed from the British public’s concept of the Bulldog breed.

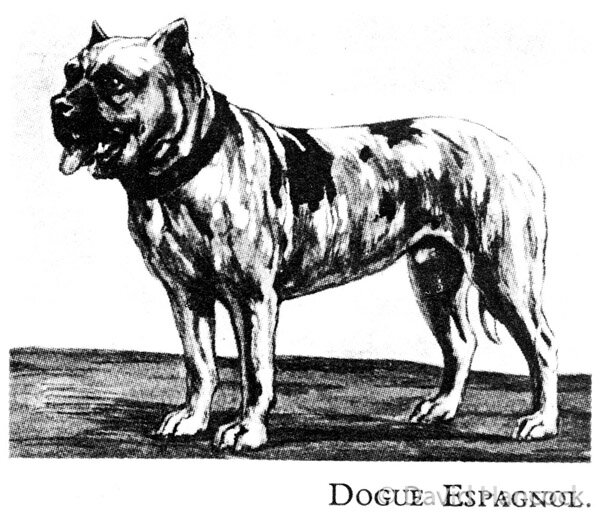

The Bulldog of bygone days was a sporting dog. In his "Wild Sports and Natural History of the Highlands" of 1919, Charles St. John wrote: "I at one time had an English bulldog, who accompanied me constantly in deer-stalking; he learnt to crouch and creep up to the deer with me, never showing himself...If a deer was wounded, he could follow the track with untiring perseverance, distinguishing the scent of the wounded animal...he would also follow the stag till he brought him to bay, when, with great address in avoiding the horns, he would rush in and seize him, either by the throat or the ear..." (Despite this inherited skill, the Bulldog is placed in the Non-Sporting Division, in the Utility Group, by the Kennel Club of Britain; in the Non-Sporting Group by the American Kennel Club and in Group 2, Pinscher and Schnauzer Type, Molossian and Swiss Mountain and Cattle Dogs by the FCI. Not one kennel club in the world recognises the modified brachycephalic type of dog as a hound or as a sporting dog.) In his The History of the Dog of 1845, WCL Martin wrote: "The Corsican and Spanish bulldogs closely resemble the English breed, but are larger. A Spanish bulldog, which we had very recently an opportunity of examining, was certainly the most powerfully formed dog we have ever seen. In stature it was between the English bulldog and mastiff, but of massive build, with thick muscular limbs, tremendous breadth of chest, and an awful (then meaning awesome, DH) head. It was very gentle, excepting when urged to make an attack, when its ferocity knew no bounds."

The Spanish Bulldog is perpetuated today in the breed of Perro de Presa Mallorquin (at one time called the 'matin of Terceira') has a similar appearance but a different origin. Sometimes called the Mallorquin Bulldog, but known to the Catalans as Ca de Bou, it was traditional to crop its ears in a rounded form to achieve an almost feline look. These dogs were widely used in dog-fighting, as the Fighting Dog of Cordoba illustrated, even being exported to the Spanish islands of the Caribbean for this purpose. I understand that in the 1960s there were no pure specimens left and the breed had to be reconstituted, with around 500 now existing worldwide. The specimens that I have seen at World Dog Shows have been calm, friendly, equable and stable in temperament. Sergio Gual Fournier, president of the Club Espanol del Ca de Bou, specialist judge of the breed and owner of the 'Almallutx' kennel, assures me that the breed is in safe hands and thriving.

The new interest in this once-neglected breed is paralleled in South Africa. The emergence of a bulldog breed like the Boerboel (literally 'farmers' bulldog) of South Africa is immensely pleasing; after years of misuse, overuse and neglect by man, this remarkable group of dogs is now receiving the recognition it deserves. The Boerboel appears to feature all the best attributes of the bulldog breeds: immense power combined with great faithfulness, physical stature combined with admirable tolerance and a temperament capable of placidity or ferocity, if its family is threatened. The Boerboel looks to be a magnificent breed, developed in a hard school by tough farmers who were threatened by every kind of dangerous predator, in testing terrain and a challenging climate. Hard-pressed pioneer farmers, however resourceful, didn't have the circumstances that exactly encouraged the conservation of rare breeds of dog. They had a need for brave powerful virile dogs and bred good dog to good dog until they obtained the desired result. The way in which the Rhodesian Ridgeback was bred by hunter-farmers is probably a model for all such dogs. Performance directed every breeding programme. Pure-breeding, handsomeness and a respect for heritage doesn't usually feature highly in a pioneer, hunter-farmer's priorities. It should be a matter of pride that the Boerboel was developed from the best mastiff-type dogs available in South Africa and brought there by soldiers, colonists and settlers from Europe. It is a breed to be proud of for that reason alone.

As a registered, purebred, recognised breed of dog, the Boerboel will need a well-worded breed standard if it is to be bred true to type and function in future years. It is disappointing, therefore, to read the first issue of this standard and assess the impact of its wording on breeders who have simply no concept of what a dog like this was expected to do on a lonely farm in the early days of South Africa. Under 'General Appearance', the Boerboel is expected to be bigger than the Boxer but shorter in the leg than the Great Dane; no mention of any Bulldog type. Under the head description, it stipulates that the nose bone must be straight, with very little or no tilting up like the Boxer and no longer nose like a Great Dane. I know of no other breed standard which tells you which features of another breed are not to be copied, without stating what the comparable features in the subject are expected to be. At a breed club show a few years ago, I was disturbed to see some giant, heavily-boned, quite gross exhibits; this is worrying. Big never means better; in breeds of dogs it sometimes indicates psychologically-needy owners!

The Boerboel is expected to be between 61 and 66 cms at the withers when full grown and weigh between 55 and 65 kgs; the breed is expected also to be active and assertive. Temperament is rightly stressed; there should be no sign of sullenness, sulkiness, surliness after reprimand or ill-temper. The dilute black colours of the mastiff group manifest themselves in this breed, with brindle, yellow (lion), grey, red-brown and brown, with or (to me sadly) without black muzzles. The intention is to develop a solid-coloured breed with no or little white. The nose must be black, unlike the Dogue de Bordeaux. The phenotype of this breed is typical of this group of dogs everywhere in the world. There would be merit however in an international Bulldog body that could rationalise the different breed standards, especially over the words used to describe acceptable colours.

The emergence of this fine breed, after a century of neglect and indifference in its native land, and its subsequent stabilisation into a distinct canine race, is not only a tribute to its loyal fanciers but also to the dogs themselves. How virile they must be to survive the climate; how robust to survive the terrain and fearsome wild opponents; how dependable in remote locations to inspire their owners to continue with them and how strong the genotype to triumph after a century of anything but pure-breeding. Perhaps the biggest threat to them in the long term is misuse once imported into Europe, misguidedness in their future design by show breeders and a closed gene pool, which they have managed well enough without in their whole history. But these pressures face all pure breeds once recognised; the closed gene pool receives undeserved worship and sickly, unathletic dogs, quite unlike their ancestors, are perpetuated in so many purebred dogs in far too many developed allegedly civilised countries. The admirable Boerboel devotees need to be alert and open-minded if their breed is to survive in the 21st century.

American breeders of American Bulldogs have been prone to rate gigantic specimens in this breed, as if size itself had virtue. Closer acquaintance with the Mastiff breed in England would soon convince them of the folly of this approach; even Mastiff breeders in America are now resorting to an Anatolian Shepherd Dog outcross to replicate the real breed. The breed of American Bulldog comes in a variety of colours, but white or mostly white is the most common. Brindle and fawn dogs are not uncommon but usually feature plenty of white. Dogs can range in weight from 85 to 135lbs, bitches from 70 to around 100lbs. The smaller specimens have a distinct American Pit Bull Terrier look to them, which is hardly surprising for their blood was used in the creation of the latter breed. Bill Hines of Harlingen, Texas, used his American Bulldogs as hog-dogs, in the classic medieval catch-dog manner, with all his stock being from old working lines.

The Alapaha Blue Blood Bulldogs are allegedly from plantation dogs of the river region of that name in South Georgia, where there are other types known as Georgia and Old English White Bulldogs. Around two feet at the withers and weighing just under 90lbs, they are commendably prized for their athleticism and agility. The image used here is of an outstanding dog from an impressive kennel. Another American keen on 'real Bulldogs' is David Leavitt, with his Olde Englishe Bulldogges. Having failed to produce what he desired from a blend of Bullmastiff, American Pit Bull Terrier and English Bulldog, he tried a different combination. He found an AKC-registered purebred English Bulldog, Westchamp's High Hopes (which also played a significant role in the production of some outstanding American Bulldogs), weighing 95lbs, in Massachusetts, and mated this dog with one of Johnson's American Bullbitches to produce the type he was seeking. Since then he has certainly bred some healthy handsome Bulldogs.

In Canada, Lolly Wilkinson of Victoria, British Columbia, has her Original English Bulldogges, fit, healthy dogs which live a lot longer than the KC-recognised type, weigh between 50 and 75lbs and stand between 17 and 19 inches at the shoulder. Unlike the show ring dogs they have muzzles! They are remarkable in their resemblance to early 19th century bulldogs in England, but because they lack the exaggeration of the type favoured in today's show rings, they are rather strangely scorned by fanciers claiming to love Bulldogs yet breeding less healthy and less traditional animals. Breeding any subject creature to a harmful design merely to conform to some ill-advised and misguided breed standard as approved by an unthinking kennel club is surely bizarre in any civilised country as we enter a new millennium. In Switzerland and Holland too, with the Gimmecke dogs earning praise, enthusiasts are striving to produce a heathier, more typy Bulldog. I admire the work of Noel and Tina Green in Australia, where their 'Aussie Bulldogs' exemplify the better type of dog: active, anatomically sound and yet resembling the real Bulldog.

But in this breed, as with some other pedigree breeds of dog, the wish to perpetuate strong breed show-points has led to harmful exaggeration. This has not happened however with the French Bulldog. The desire for a smaller more passive dog, with the pugnacious look which so typifies the Bulldog, led misguided fanciers in the past to outcross with Pugs, mainly to shorten the muzzle. The seeking of an indomitable, 'no surrender' stance in the breed has led to poor front quarters, with specimens in Victorian times displaying all kinds of quite dreadful structural faults. The KC show Bulldog is now a caricature of itself. I have judged both the American Bulldog and the Victorian Bulldog and been impressed by their soundness, both in physique and temperament. The 'Aussie Bulldogs' of the Greens look like real Bulldogs. Some American and Swiss breeders are producing healthier sounder dogs. I have also seen 'Sussex Bulldogs' and 'Dorset Old Tyme Bulldogges', currently being bred by well-intentioned fanciers, that looked healthy and unexaggerated, active and agile, breathing and moving freely.

For a group of well-intentioned fanciers to come together as the Dorset Bulldogge ones have, and produce not only a healthier dog, able to live a long and active life, but one resembling the real bulldog of past centuries, is heart-warming. The show ring specimens at Crufts are miles away from the agile, athletic dogs once renowned all over the world as gutsy, determined, never-say-die exemplars of our national character. These Dorset Bulldogges really do look and act like bulldogs and are a major step forward in restoring the national breed to us, in the form we once prized. All power to them. May they and their dogs go from strength to strength. They certainly deserve the support and interest of every patriotic dog-lover.

I have some concerns over the breed standard being worked to by the Sussex enthusiasts; it lacks detail and advises some features that need greater thought. Yellow eyes are desired and splay feet are not a fault; I would question the sense of both. A Bulldog of 120lbs is more the size of a Bullmastiff or American Bulldog; is that really what they are seeking? When I wrote a breed standard for the Victorian Bulldog Society some years ago, and contributed words for the Dorset Olde Tyme Buldogge design, it sought different criteria. I favour a weight of 65 to 80 lbs for males, with a height at withers of 17 to 19 inches. I stressed the word 'balance'; advised against heavy bone and sought the classic anatomy of the holding dogs, like the early-19th century dogs and their predecessors. In his 'British Dogs' of 1903, WD Drury wrote:

"Anyhow, the Bulldog of today is an entirely different animal, both physically and mentally, from the Bulldog of fifty years ago. Then he was a leggy, terrier-like, active brute...As to whether the fancier has improved the breed constitutionally is a moot point. Type has certainly been made more uniform; but this in many cases has been at the expense of other qualities." It has been at the expense of the dogs in many ways.

The English Bulldog should be: a powerful canine athlete, able to move like lightning over a short distance, with great neck and shoulder strength and a substantial jaw, able to display considerable agility - a healthy animal with a symmetrical, well-balanced physique free of exaggeration. It has never needed a massive head, a short body, with elbows and shoulders looking as though they are a late addition; it should be able to run just as its own ancestors could. It doesn't have to suffer from distressing eye conditions such as ectropian and entropian, incapacitating respiratory conditions such as trachial hypoplasia, overlong soft palate and laryngeal paralysis, congenital heart conditions like pulmonic stenosis, ventricular septal defect and mitral insufficiency, a host of dental and skin problems and vertebrae deformities. In England, we should be ashamed of what we have done to the world-famous, rightly-renowned, breed of Bulldog; breeders of the other bulldog breeds around the world should take note and vow that their breed will never be distorted in such a way. The world's Bulldogs are an important feature of the dog world and thoroughly merit protection from those deranged souls intent on exaggerating their breed points to a harmful degree. The Kennel Club of Britain must now lead the way in the breeding of a sounder, historically-correct, healthier and longer-lived Bulldog.