1142

SETTERS IN SCOTLAND

By David Hancock

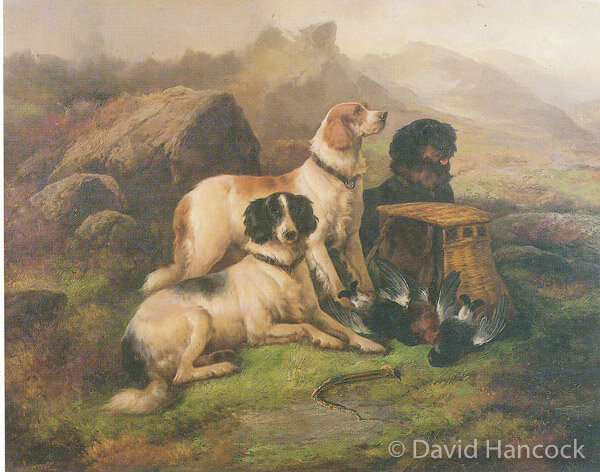

If you study the paintings of country sports in Scotland in past centuries, you could be forgiven for thinking firstly, that setters were as much used as Deerhounds in the deer-hunt, and secondly, that the setters used on grouse moors there utilised English Setters, by modern definition, ahead of Gordon Setters. I have in mind depictions such as William Walker Morris’s After the Hunt, Richard Ansdell’s Waiting for the Guns, James Syers’ (jnr) A Ghillie with Dogs, Frank Stratford’s Gun Dogs and a Pony, Robert Cleminson’s Gundogs resting by a Pony and his A Pony and a Dog, John Morris’s Gun Dogs and Pony and Frederick Gilbert’s On the Alert. In some of these, and no doubt there are many more, the setters are the dogs in focus rather than the Scottish Deerhounds that actually pursued the quarry. In each of these paintings, the setters depicted resemble English Setters by coat colour, with one black and tan exception in John Morris’s painting. (Two other John Morris paintings: Setters On A Moor, of 1889 and Setters with their Bag, of 1897 do show a black and tan setter – with mainly white ones. Richard Ansdell’s Setters of 1883 do show black and tan setters, so he clearly knew of them too.) It would be wrong however to assume that the setters used on the moors and depicted in this way were English Setters, just because of their coat colour combination. Breed titles are kennel club conveniences rather than sportsmen’s names for them. But evidently, setters in Scotland were not only black and tan or tricolour. In the early 19th century setters were not bred by or for their coat colour.

As well as the setters of England and Ireland by name, we could so easily have had a Welsh Setter, had the old Llanidloes Setter been promoted, and a Scottish Setter, distinct from the Gordon Setter as a recognised breed. The registration of the Irish Red and White Setter, in addition to the Irish Setter, as a distinct breed, has given us a handsome, elegant, stylish addition to our native setter breeds. All the setter breeds are struggling to retain popularity, as shooting preferences change and show ring fads dictate, but they represent an admirable component of our distinguished gundog breeds. We now favour the all-rounders - the hunt, point and retrieve breeds from overseas, but the sheer style of our own Pointer and setter breeds have an appeal of their own. We also failed to conserve not just the Llanidloes dog but the Scottish Setter too, whilst our Laverack and Llewellin Setters became subsumed into the English breed, although Llewellins are still bred in the United States.

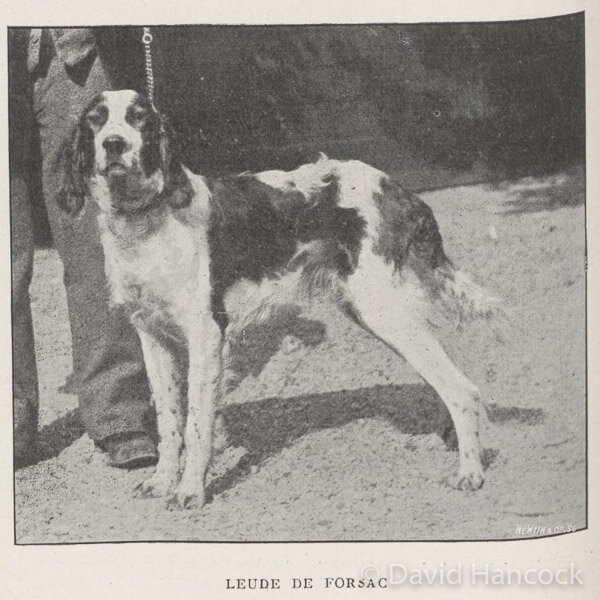

The setter of Gordon Castle, developed by the Duke of Gordon, is a distinctive breed, now favoured in just black and tan although the Duke liked the tricolours too. Mainly white dogs do crop up in Gordon Setter litters however, displaying the range of the gene pool, as the field trial champion Freebirch Vincent demonstrated so well at the end of the last century. But, just as the Irish Red and White Setter has earned breed status, a similar argument could be made for the black and white whelps in Gordon Setter litters, to be recognised as Scottish Setters and given separate breed status. It's of interest that in the French show rings a century ago, the mainly white, but black and white, setters were usually described as Scottish Setters. The English Setter can be black and white but only in blue belton, not in a parti-coloured black. I have seen them in black flecking but not what used to be called piebald. In the setter breeds coat colour mainly separates the breeds, but breed identity could be more specific. After the successful registration of the Irish Red and White, could there not be room for the Scottish Black and White?

Historically the setter coat colours ranged from the liver and whites of the Prouds at Featherstone Castle, keepers Laidlaw at Edmond Castle and Grisdale at Naworth Castle; the Earl of Southesk's, the Marquess of Anglesey's, at Beaudesert in Staffordshire, and Lord Lovatt's tricolours; the lemon and whites of the Earl of Seafield; the milk-whites of Llanidloes and the black and tans (and tricolours) of Gordon Castle, to the black and whites of Lort of Kings Norton. In Ireland, O'Keefe and Baker of Tipperary favoured the white and reds (as the Irish called them), Capt. Butler of County Kerry went for the black and whites, whilst the reds were promoted by the Marquess of Ely, Lord Farnham, Redmond in County Dublin and the Cavendish family of County Cork. Lord Ossulton in Northumberland, Lord Hume of Tweedside, Harry Rothwell in Westmoreland and an English clergyman, who wrote under the nom-de-plume of “Sixtyone” and rented the whole shootings of Lewis and Harris in the 19th century, each favoured the all-black setter, renowned for its glossy waterproof coats and ‘stout feet’. It has been argued that the black setter lives on the Flat-coated Retriever, with its solid black or liver coat and setter-like outline very much a breed feature.

In the time of the Stuarts, the setting dog was used to hold game birds to ground, often with a hawk overhead to keep the birds from flying, while a net was carefully drawn over them. Then with the introduction of firearms and later 'shooting flying', setters were needed, along with pointers, to indicate and then put up feathered game. In pursuit of this function, the setting dog breeds developed both here and on the continent, and were widely traded, with a high value on a trained and effective dog. Whilst our setter breeds were evolving here so too were the 'epagneul' breeds on mainland Europe. In time certain coat colours were favoured by individual sportsmen both here and abroad. The epagneul breeds varied all over mainland Europe but all had that definite setter appearance: feathering on the tail and legs, a distinct occiput and enormous style when seeking game scent. In Holland the Drentse Patrijshond and Stabyhoun emerged, in France the Epagneul Francais, in Germany the Munsterlander (and later the Langhaar and long-haired Weimaraner). In Britain, distinct strains were stabilised, often exemplified by their coat colour, with far greater variety than nowadays. The first time I saw an Epagneul Francais I thought it was an English Setter - in a liver and white coat. But the English Setter was highly popular in France in Edwardian times.

It is foolish for setter breed historians to claim a long and pure lineage for their favoured breed. Good setters were mated to other good setters irrespective of colour. The landed gentry went on their Grand Tours, sometimes taking their dogs with them through Europe and sometimes coming back with a dog that had impressed them. It was easier to bring foreign dogs into Britain in every previous century than the twentieth. In 1563, Lord Warwick wrote to his brother the Earl of Leicester from Le Havre: “I thank you for sending me so fine a horse. In return, I send you the best Setter in France…” The epagneuls influenced our bird-dogs. The Americans still recognise the Llewellin Setter as a separate breed. They consider that the breed comes from three lines, each bred to Laveracks. One of these lines, from 'Rhoebe', the greatest field trial winner-producing dam of all time, passes on the blood of her sire, who was the great grandson of a Gordon Setter and a dam which was half Gordon and half Southesk Setter, a strapping tricolour strain from Forfarshire. A most knowledgeable American sportsman, Joseph Graham, writing in 1904, in his informative The Sporting Dog, stated that: "...they (i.e. the claimants of the Llewellin as a separate breed) would as well go further and drop the 'pure' idea altogether, letting Llewellin blood stand for what it is -- an influential but not separate element in English setter breeding". In Britain we have long held that view.

Joseph Graham also states in his book that: "Purity of race is a good thing when it is good. Sometimes it is a misnamed conglomeration, and sometimes it needs breaking up and disturbance". Are we going to persevere with purity of breeds when it is "not good"? Here are some critiques in recent years on our setters in the show ring: Gordons - "Unless something is done quickly by the top breeders, I see no hope for the breed, because the puppies were so bad." Irish Setters - "I found quality in depth lacking, and the movement was on the whole very bad." Irish Setter dogs - "One of my main observations is the weakening of the overall body shape, the breed is losing genuine spring of rib and becoming too slab-sided." Gordons - "I was however rather shocked to find a lot of poor angulation front and rear, upright shoulders predominated...also too many straight stifles." English Setters - "Poor mouths and movement were the chief faults but straight stifles and heavy shoulders were to be found." Perhaps the setter breeds need expanding!

In his informative The Book of the Dog, the under-rated Edwardian dog writer James Watson wrote: “In using the name of Gordon setter for the black and tan variety we do so because it has become universal, though it is undoubtedly a misnomer, if it is meant to specify that the breed so named originated with the Duke of Gordon, or was alone and specially fostered by him. That this nobleman, who died shortly prior to the oft-mentioned sale of dogs in 1836, by no means confined himself to a special colour is an entirely wrong idea.” Those firm words are supported by plenty of evidence to back his forthright statement. In his wide-ranging A Survey of Early Setters of 1985, an admirable piece of research, Gilbert Leighton-Boyce refers to an account of a visit to the Duke of Gordon’s kennel that took place in 1862. This read: “…we beguiled the way by a chat with Jubb, the head keeper, whose seven-and-thirty black-and-white tans were spreading themselves…Originally the Gordon setters were all black and tan…Now all the setters in the castle kennel are entirely black and white, with a little tan on the toes, muzzle, root of the tail, and round the eyes. The Duke of Gordon liked it, as it was both gayer and not so difficult to back on the hillside as the dark-coloured…The composite colour was produced by using black-and-tan dogs to black-and-white bitches…” Breeding for colour was clearly intended.

Against that background the setter colours of today look rather impoverished; we have become transfixed by the aura of the pedigree. Not so the Duke of Gordon who was described as "not a man to confine himself to shades and fancies"; he once used a Spitz-wolf cross on deer courses. His black-and-whites may have been a result of using a brace of English Setters given to him by Captain Robert Barclay of Urie. In New Zealand, a litter of black and tans was once produced from an unplanned mating of a blue belton English Setter to an Irish Setter bitch. The Duke would not have approved the setters named after him needing to possess the now mandatory black and tan jacket of the breed. Not so too the founder of the modern setter, Laverack, who wrote that a change of colour was as good as a change of blood. The advent of dog shows has brought an absurd conformity, restricted breeding programmes to the diktat of the breed standard's stipulations and led to mis-marked but otherwise high-quality dogs being lost from the gene pool. The recognition of a Scottish Setter, parti-coloured in black and white, could spark a new look at our fine setter breeds, and a national gundog breed, by name, to further advertise the fine sporting dogs created in that country.